True, it’s not even yet midsummer and we’re still more than half a year away from Christmas. But I do have a perfectly valid reason for celebrating Christmas in June with this week’s featured beer, Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël from the French brewery Brasserie au Baron. It is a Christmas beer, but it’s also named for Saint Medardus, whose feast day is celebrated on June 8th, which was just this past Tuesday. And even if you somehow missed that observance, you now have a good half a year to score a bottle of this excellent French ale in time for Christmas.

Brasserie au Baron has its origins in a bistro run by the Bailleux family since 1973 in Gussignies, a small French town along that lies along the river Hogneau right at the border with Belgium’s Hainaut province in the Francophone south of that country. The Bailleux family began operating a small brewery in the village in 1989 and its flagship beer was named Saint-Médard after the local church, the Église Saint-Médard. Brasserie au Baron now produces several beers under this name, including their Christmas beer, the Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël, a saison-style ale made with elderberries.

The Église Saint-Médard in the picturesque French border town of Gussignies, home of the Brasserie au Baron.

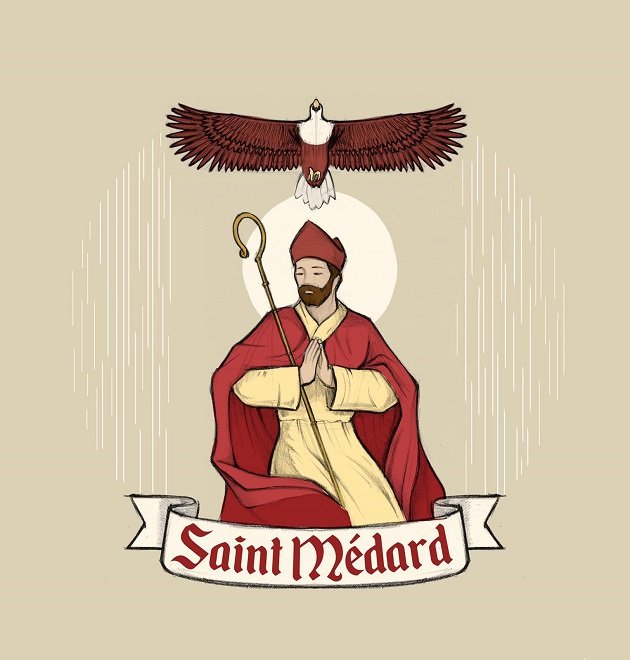

These days, the beer’s namesake is a rather obscure figure, but Médard – or Medardus – was a popular and much-venerated saint in the Middle Ages. Born in Salency in Picardy around 456 during the very last days of the Western Roman Empire, he succeeded Alomer as bishop of Vermand in 530. While his episcopal exploits during these turbulent times included combatting the last vestiges of Frankish paganism, he is also remembered for later moving the seat of his bishopric from Vermand to Noyon, chiefly for the defensive advantages provided by the relict Roman walls encircling the latter, but also – according to some sources – because Noyon produced superior wine. And fittingly, as a native of this region that straddles the line between the barley-growing, brewing north of Europe and the grape-growing, winemaking south, Medardus is a patron saint of both brewers and vintners. He was also apparently much disposed to laughter and is often portrayed with his mouth wide open; for this reason, he’s also invoked by sufferers of dental maladies such as toothache.

But it’s for the lore concerning the weather on his June 8th feast day that Saint Medardus is best known today, by those who remember him at all. His hagiography describes an incident in which, as a child, he is said to have been miraculously sheltered from a rainstorm by an eagle hovering over him with outstretched wings. This episode is the most popular depiction of his life in medieval iconography and it also appears on the label of Saint-Médard beers, though it depicts Medardus not as a child but as a bearded, wizened bishop grasping his crosier. Since he seemed to enjoy such good luck with weather – and could count on the divine intervention of avian umbrellas floating overhead – the feast day of Medardus became a much-anticipated date for folkloric prognostications of summer rains, in the exact same role that Saint Swithun’s Day played to the English farmer. In France, the proverb is “Quand il pleut à la Saint-Médard, il pleut quarante jours plus tard” which is more or less equivalent to the traditional English saying:

St Swithin’s day, if thou dost rain,

for forty days it will remain

St Swithin’s day, if you be fair,

for forty days ‘twill rain nae mair.

S. Médard, évêque (“St. Medard, Bishop”) from Les Images De Tous Les Saincts et Saintes de L’Année (“Images of All of the Saints and Religious Events of the Year”), a 1636 etching depicting the most famous episode in the life of this saint, by French printmaker Jacques Callot (c. 1592 – 1635).

If that’s not enough superstition for you, the Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël is brewed with elderberries, the dark, purplish fruit borne by several trees of the genus Sambucus. There are few plants that feature as prominently in traditional folk beliefs as the elder. Among its many suggested uses, planting it to ward off witches and evil spirits is one of the more prevalent, while other traditions warn that bringing parts of the plant into the home is sure to summon the presence of ghosts or even the Devil himself. In the English countryside, an elder tree rooted alongside a cottage or farm was thought to prevent lightning strikes, while in his De materia medica, the first-century Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides declared that drinking wine steeped with elderflowers counteracted snake venom. The seemingly endless and often contradictory folk beliefs surrounding the elder reveal a plant just as likely to offer healing and good luck or misfortune and suffering. Adding to the elder’s sometimes ill repute among pious medieval Christian was its role in the suicide of Judas Iscariot after his betrayal of Christ: the anonymous 14th-century travelogue The Travels of Sir John Mandeville identifies a specimen of this tree in Mount Zion in the Holy Land as “the tre of the elder, that Judas henge himself upon, for despeyr, that he hadde, when he solde and betrayed our Lord.”

Two birds – probably intended to represent eagles – are carved into the stone Romanesque tympanum of the ancient Church of St Medardus and St Gildardus in Little Bytham, in Lincolnshire, England. While a few dozen places in France were named for Saint Medardus, this dedication in the British Isles is unique. The earliest parts of the church date to the Anglo-Saxon era.

Though elderberries have an unpleasant taste when raw and contain alkaloids that are toxic to mammals (birds seem to have no problem enjoying them), cooking improves their flavor greatly and destroys these poisonous substances. Medieval herbalists and folk medicine traditions attributed a seemingly endless number of cures to all parts of this flowering perennial; the berries, leaves, bark, and flowers of the elder could be called upon to fulfill all manner of curative roles. You might be hard-pressed to find it in your local pharmacy today, but in the past, the elder tree was considered a reliable one-stop botanical source for emollients, vulneraries, stimulants, diuretics, laxatives, alteratives, purgatives, emetics, and other pharmacological remedies.

Black elder, one of several species used in European culinary and medicinal traditions, as depicted by Belgian painter and botanist Pierre-Joseph Redouté (1759 – 1840) in Traité des arbres et arbustes que l’on cultive en France, par Duhamel. Nouvelle édition, avec des figures, d’après les dessins de P. J. Redouté, 7 vols. (1800 – 1819).

On top of that, elderberries and elderflowers taste good as well, provided proper care has been taken to nullify their poisonous effects. The most famous culinary application of the plant these days is in the French elderflower cordial St-Germain, but lesser known traditional uses include jams and pies, battered elderflower fritters, a Romanian soft drink called socata, and the German elderberry soup Fliederbeersuppe. While alcoholic beverages employing elderberries are few and far between in our age, elderflower ale was very popular in earlier times, as were elderberry wine and a strong, barley wine infused with elderberries known as ebulon. In 1890, John Bickerdyke provided a recipe in his The Curiosities of Ale and Beer:

Ebulon, which is said to have been preferred by some people to port, was made thus: In a hogshead of the first and strongest wort was boiled one bushel of ripe elderberries. The wort was then strained and, when cold, worked (i.e., fermented) in a hogshead (not an open tun or tub). Having lain in cask for about a year it was bottled. Some persons added an infusion of hops by way of preservative and relish, and some likewise hung a small bag of bruised spices in the vessel. White Ebulon was made with pale malt and white elderberries.

Ebulon was probably an obscure memory of English country brewing even in Bickerdyke’s day and there’s no reason to suspect that the Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël was directly inspired by it over a century later; its use of elderberries is likely just a product of the inspired experimentation and rustic resourcefulness that Franco-Belgian farmhouse brewing is known for. Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël calls itself a saison, but it feels richer than those lighter, refreshing Belgian ales of summer, having more in common with the heartier, often darker bières de garde made by French brewers just across the border in Nord-Pas-de-Calais.

Elderberries do make a welcome but subtle appearance in the Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël, tinting this dark garnet beer with purplish highlights beneath a remarkably dense and foamy head. A fruity, cotton candy aroma suffuses the bouquet, boosted by a lovely combination of poached cherries, toasted hazelnuts, buttery toffee, and a dusting of dark chocolate beneath. This is a delicate but generous beer, showcasing warming flavors of caramel, spicy brown bread, and sweet malt, with a refreshing hint of elderberry and an earthy hop bitterness coming through in the long, dry finish.

While it may not be an ideal beer for the hottest, most oppressive days of summer, I found that the Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël made for a surprisingly enjoyable drink on a relatively cool evening in early June. And for the record, it rained like cats and dogs with thunder and lightning at my house on Saint Medardus’s Day this year and I didn’t see a single hovering eagle to provide any shelter from it.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Brasserie au Baron: Saint-Médard Cuvée de Noël

Four out of five feathers (Excellent)

Leave a Comment