Birdwatchers love making lists, with the year list one of the most important. In my younger days I always kept year lists: my best ever year was 1986, when I topped the 1,000 mark thanks to trips to Australia, Kenya and various European destinations. It’s a total I’ve never approached since, which might explain why in recent years I stopped counting. However, 12 months ago I decided to do a 2023 year list, so now, with 2024 just hours away, I can reveal the results.

They’re not, alas particularly impressive. My British total was a mere 172 species – not bad, but not very good. However, I have to put it in perspective by explaining that during the year I hardly ventured out of East Anglia, and almost every bird was seen in Suffolk or Norfolk – I live on the county boundary. Both counties are among the best in Britain for birds, but to knock up a big total without travelling far you really have to live on the coast. I live 45 miles (or if you prefer, 73km) from the sea, so to get to there takes me more than an hour in the car, though the traffic is usually light, the roads quiet.

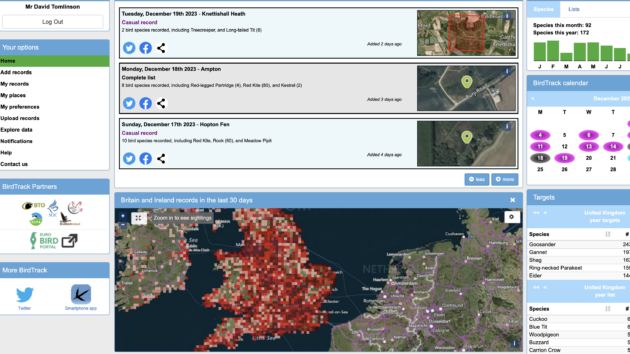

I’m not a twitcher, either, so I rarely, if ever, go in search of a bird, or birds, that someone else has reported. Every one of my 171 species was a bird that I found myself. I record all my bird sightings on BirdTrack, (see screen shot, above) which is the British Trust for Ornithology’s equivalent of E-bird. It’s an excellent, easy-to-use app, and does allow you speedy access to all your records. It keeps a monthly record of sightings, so I can tell you that it was in February that I recorded my highest monthly species total (106), while my lowest total was in August (39). I only scored 43 in March, but that was because I was away birding in Portugal and Estonia.

My overseas trips did boost the overall year list considerably. I also travelled to Kerkini in Northern Greece in June and Kefalonia in south-east Greece in October, so my overall year list was a more satisfactory 272 species. Though I also log all my overseas sightings on BirdTrack it doesn’t give me a running total for them, just my British records. This may be because I’m not competent enough to set it up to do so. I also have an Excel spread sheet for my European year list. I failed to score any lifers in 2023, which isn’t really surprising as there are very possibilities left for me in Europe, or even the Western Palearctic.

In January I managed to find most of the wintering birds I can expect in this part of the world, so my month’s list comfortably passed the 100 mark. My 100th species was a Spoonbill. This was an interesting sighting, as it’s only in recent years that these striking birds have started over-wintering in East Anglia. These birds (usually juveniles) are clearly linked to the growing breeding population in the region. Spoonbills nested in Britain for the first time for 300 years in 2010, when a small colony became established at Holkham in North Norfolk. Today that same colony is thriving, with an impressive 90 birds fledged in 2023.

One of my most satisfying ticks in January was another wetland bird, a Bittern. Though it was a species I was confident of finding in the spring, a pleasingly confiding individual lurking on the edge of a reedbed allowed me to take its photograph (above). I encountered a delightful flock of Snow Buntings on the same day, another species that it’s always good to see.

In February it was a case of finding those species that had eluded me so far, so I was pleased, for example, to discover a couple of Mediterranean Gulls while checking through a flock of Black-headed Gulls on the coast near Yarmouth. I always undertake a number of short timed surveys for the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust’s Big Farmland Bird Count in February, and though the counts didn’t add anything to the year list, they were memorable for finding big flocks of finches and buntings, while a daylight-hunting Barn Owl was a pleasing sight. Later in the month, a flock of several hundred Avocets on the River Alde was also memorable.

Ten days in southern Portugal in early March gave a major boost to the year list, as spring comes early to the Algarve, so I was instantly adding numerous spring migrants to my rapidly growing list. Swallow, House and Sand Martin, Yellow Wagtail and even Cuckoo were all birds I was a sure of seeing a month later at home, but it was cheering to find them so early. Pallid Swifts were already back at their breeding sites, while the marshes provided a host of waders, including year-ticks such as Whimbrel, Curlew Sandpiper and Kentish Plover. Inland in the Alentejo I found Great Spotted Cuckoos and the first returning Short-toed Eagles. However, locating the special steppe birds of the Alentejo proved a challenge (I should have used a local guide), but eventually I found both Great and Little Bustards, Black-bellied Sandgrouse and numerous Calandra Larks.

Estonia at the end of March provided quite a contrast to warm and sunny Portugal. The temperature rarely climbed above freezing, and birding was hard work. The rewards were, however, hugely satisfying. Big flocks of Long-tailed Ducks were a delight, but our target bird, Steller’s Eider, let us down – we found just a single female, not the flocks we were expecting. We only saw a female Capercaillie, too, while our views of Hazel Grouse were fleeting. On the plus side, Waxwings and White-tailed Eagles (10 in the sky at once) were great to see.

April and May in England gave me the chance to catch up on the breeding birds of my area, including Mandarin Duck, Goshawk and Stone Curlew (the photograph below is by courtesy of my friend David Addy – I photographed the same bird, but David’s picture is much better, as it captures the bird’s Breckland habitat). One of the delights of spring are the concentrations of Hobbies that can be found at local wetlands in mid May, though photographing them is always a challenge, and I’ve yet to get a shot I’m really pleased with.

In June I enjoyed a visit to Lake Kerkini in Northern Greece. It was a chance to catch up with most of the Balkan specials, such as Masked and Lesser Grey Shrikes, Rock Nuthatch and Levant Sparrowhawk. I found a singing Olive Tree Warbler, too, but it didn’t want to have its photograph taken. Kerkini is a safe bet for all the European herons, plus Spoonbills and both Dalmatian and White Pelicans.

Back home in England for the summer, my listing lost its momentum, as there wasn’t much more to find. I turned to butterflies instead, successfully finding Large Blues, one of Britain’s rarest species, and a successful reintroduction after extinction in 1979. New bird ticks were now becoming elusive, and even Kefalonia in October failed to add much. Delightful island though it is, it’s not a great place for autumn migration, though I did manage to find a few passing Whinchats, a bird that had eluded me earlier in the year. A single Eleonora’s Falcon was a very pleasing if not unexpected, and a year-tick.

I did plenty of birding in November and December, but there were now few possibilities to add to the year list. One was Shore Lark, but despite considerable efforts the wintering birds at Holkham managed to elude me. However, I was delighted to find a Razorbill, fishing enthusiastically in a Norfolk harbour. A Rock Pipit, close by, was also a year tick. Waxwings proved hard to get, despite plenty of flocks being reported. I eventually found a single bird, sitting rather forlornly in a hawthorn tree with a couple of Woodpigeons. It wasn’t a year tick, of course, as I had seen them in Estonia, but it was the last new bird of the year for my British list, and a highly satisfying one at that.

Will I be listing again in 2024? The answer is yes. On New Year’s Day I will try and find 70 species locally to start the year, while updates on the list’s progress will be reported here on 10,000 Birds. My targets are 200 species in Britain and 300 in Europe: a little bit of ambition never does an harm.

Leave a Comment