As we learned in Basic Sorcery 101, casting spells is a complicated affair. Conditions must be ripe and ready; it is essential for the senses to be tuned in to the correct frequency. Else it’ll be an exercise in futility. The unspoken ingredient in this is patience – if it doesn’t work the first three hundred times, that doesn’t mean the 301st attempt will also be a failure. Probably explains why wizards typically have long, grey beards. This ratio of success to failure bears eerie similarity to the probability of encountering a mixed flock in a tropical jungle.

In tropical rainforests, it often looks as though the trees must be positively dripping with birds. Massive, bromeliad-laden boughs thirty metres in the canopy should be cradling all manners of avian diversity. Far too often, though, we put ourselves in a place like this and find the silence deafening. Especially evident for forests that span hundreds, even thousands of square kilometres – one can easily spend a couple hours scanning at the risk of neck strain. Fortunes make an immediate about turn upon the arrival of a mixed flock, however.

The phenomenon of a mixed species flock has been discussed at length among birders, as it is a poignant illustration of the juxtaposition of despondence and exuberance. If you’re wondering what is a mixed flock, or why do birds of different species band together instead of sticking to their own kind – in fact if you have any questions about mixed flocks whatsoever – you can find all answers in this excellent post from our Ask A Birder series by Wenyi Zhou here.

The mixed species flock courses through the forest, without regard for where birders’ eyes are. They are intent on finding food and staying alive. Within their structure, they cooperate and compete. Nevertheless, they move as one creature. They disrupt the quiet with their often frenetic activity, even if for a few minutes at a time. They may trapline food sources, and they can band together for specific targets – I’ve seen frugivorous flocks as well as separate insectivorous flocks. Each brings with it a lottery of common and uncommon sightings for the patient birder.

Of course, it must be said that this type of activity is not something that tends to happen if one is chasing a particular sightings. A mobbing flock that can be attracted to the audio playback of alarm calls is not the same thing – not to mention deeply unethical and disruptive.

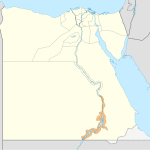

One afternoon a few weeks ago we were relaxing at our lodge in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, enjoying the rain that had gathered from around noon (not to mention the relief of having survived the morning’s gorilla trekking). Thick clouds and cool air persisted until long after sunset – a sunset which we never saw due to the aforementioned thick cloud cover. Activity was slow but peppered with occasional sightings of Cinnamon-chested Bee-eater, a pair of which sallied for insects next to the veranda. On the flowering plants near to the reception area we would catch glimpses of a male-female pair of Bronze Sunbird; there was a Levaillant’s Cuckoo that was also prowling undeterred by the misty conditions. Our afternoon coffee was interrupted by a pair of White-necked Ravens that landed on the roof, occasionally peering around the corner at us.

As the afternoon wore on, the sheer coziness of the setting charmed even the most ardent birder energy within me. The temptation to kick off the boots and curl up with a blanket was undoubtedly massive – but we still managed to poke around further afield to good effect. Sightings of Green-throated Sunbird and more importantly the incredibly range-restricted (and gorgeous) Purple-breasted Sunbird made the short sojourn worth it. The dismal weather still played on our spirits, however, and we returned to the lodge. By this time, the quietness of the impending night was evident. Darkness seemed to lurk over the adjacent ridge, its fingers encroaching from all sides in the absence of the direct, warming light of the sun.

I have a habit of staying out and photographing until dinnertime – pushing the limits of my gear to a point beyond which lie a couple scores of unusable images. Long after folks give up hope, I am typically still on the lookout. Despite not seeing the signs of any birds, I stuck around. Did I mention patience earlier? Staring into the void pays off, especially if the void is stuffed with foliage. There was little sound, this flock moved in silently. First I noticed a sliver of movement, then there was another, and another. I barrelled down the side of the lodge and made myself small and squeezed the shutter until they moved off.

This is the magic of the mixed species flock; the absence of a warning or any prior indication that endorphins shall be flowing unabated. Muscles tensed, attention focused. For a brief moment in time where the observer crosses paths with a couple dozen birds of disparate backgrounds, in quiet reverence of the spirit of coexistence – all too soon it is over. In that moment, however, there is no concept of time. It could be ten minutes or ten seconds. Shifting from one movement to the next, there is familiarity followed by what the hell is that.

Paying homage to the mixed species flock, I share here a small collection of the birds I managed to see in that fleeting intersection. Do enjoy and feel free to share your experiences as I’m certain every birder encounters this at some point.

Yellow-rumped Tinkerbird

The highly disjointed range of the Chubb’s Cisticola makes it a target species for many birders.

African Dusky Flycatcher

The Brown-throated Wattle-eye is one of the few birds that was named after the female of the species. Pictured here is the male, sans brown throat.

A Bronze Sunbird got in on the action as well. It was difficult for me to see what they were feeding on.

Many frames involved more than a single bird. This Baglafecht Weaver was interrupting my view of a Chubb’s Cisticola.

This Red-headed Bluebill was difficult to miss, and was the first indication that there was something happening in the shrubbery.

A greenbul that threw me for a loop turned out to be a Little Greenbul. I had zero idea but my colleague and great friend Washington has been very helpful in identifying all birds I cannot. This bird appeared briefly along with a Grey-headed Nigrita that was passing through much higher up.

Green-headed Sunbird, glowing in the darkness.

Your words are so evocative, Faraaz! Love this post, and these photos. But I hate those specific birds, since they showed up just as I was away! ?

Haha thank you, Preeti! Right place, right time!

Mixed species flocks are called ‘bird parties’ in Africa, which I think describes the whole concept really well, both from the point of view of the birds and of the birder.

Oh very cool, I never knew that. Makes perfect sense!