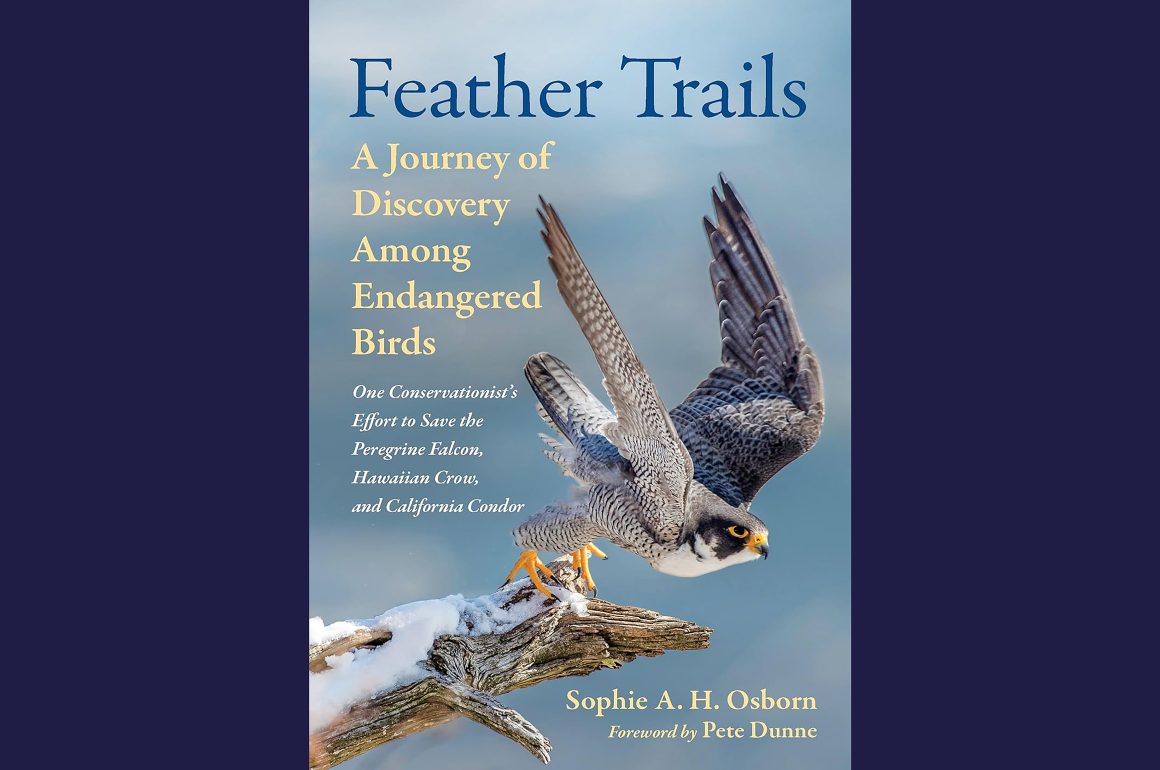

Endangered. Extinction. Research. Conservation. These are the words that define so much of our conversations about the natural world today. The chapter titles of Feather Trails: A Journey of Discovery Among Endangered Birds represent both ends of the spectrum: “A World Full of Poisons,” “Malaria,” “Forest Intruders,” “Lead Shock,” “Shot.” But also: “Delisted,” “Growing Up,” “Second Chances,” “No Tags.” And within these chapters are three marvelous stories told by Sophie A. H. Osborn, a passionate field biologist who participates to the core of her being in three re-introduction projects aimed at saving three very different, endangered species: Peregrine Falcon, Hawaiian Crow (‘Alala)*, and California Condor. Sophie Osborn’s stories are personal and inspiring, but this is more than a personal memoir. Her experiences are framed within the larger scientific histories of how once common species become endangered, and of how people and organizations have strategized and explored controversial paths to bring their numbers up and nurture them till they fill our skies.

The first two sections on Peregrine Falcons and Hawaiian Crows take place in 1991 and 1992, when Osborn, starting out on her wildlife career, takes jobs involving the observation and care of young birds new to freedom and the wild: five Peregrine Falcons bred in captivity and released in Wyoming; five Hawaiian Crows, taken as eggs from crows nesting in the wild, reared in captivity, and released on the island of Hawai’i . Both sites are in the middle of wilderness, thousands of feet above sea level, both jobs involving total immersion into the lives of her charges and their unique habitats, working with another young colleague but otherwise almost totally isolated from ‘civilization.’ The third section takes place a little later in Osborn’s career; she is field manager for the California Condor Restoration Project at the Grand Canyon, a job that is less isolated, but in some ways more complex in its visibility to the larger world.

In every section, the focus is almost totally on the birds, though there are hints of some of the more personal challenges Osborn faced as a smart woman in a field not free from gender discrimination, a thread she expands on in the final chapter. She takes us through the steps of getting the young birds ready for release, describes the housing of the pre-released birds–a hack box on a cliff, a huge aviary in the middle of tropical forest, a pen atop the Vermillion Cliffs, the anticipation and joy of the release itself. And then there is the real work, the days (years for the Condors) of observing and noting behavior, tracking each released youngster (five Peregrines, five Hawaiian Crows, many Condors), making sure the birds stay healthy and adapt to their newly wild environment.

It’s not easy. The tiercels (young Peregrines) must deal with Golden Eagles, Ravens, adult Peregrines, and foxes; they must also learn to navigate the skies and make their own kills, luckily these skills appear to be innately learned. The Hawaiian Crows face much more destructive threats–extreme loss of habitat; malaria, the scourge of so many Hawaiian species; predators–rodents, cats and the ‘Io, the Hawaiian Hawk. This is the most intense, tragic section. Osborn leaves at the end of her brief tenure with hope that her charges will remain healthy and independent (one crow has already been treated for malaria and survived). Sadly, the ‘Alala do not survive, not her birds, not the neighboring wild birds, not the Hawaiian Crows released in 2016 with great hopes for re-introduction. As of 2024, the ‘Alala are extinct in the wild though they live on in captivity. This is the chapter where Osborn talks about “second chances.”

California Condors are thriving now, mostly, but Osborn’s experiences in the early 2000’s were years of triumph and heartbreak. Lead shot injured and killed condors young and old, lead in the carrion they ate, lead in the bullets that hunters shot at them. Coyotes took carrion from young Condors and then killed the weakest ones. And then there were the recently released condors who did not realize they should not be around people, behavior that would eventually endanger them in many ways. Osborn gives story after story of having to “haze” young condors away from admiring crowds and off cliff sites accessible to coyotes (it seems that running and yelling at the top of your lungs is a job requirement). She also joyfully relates seeing through her scope “the first wild-hatched condor nestling in recorded Arizona history” (p. 286). Because with the heartaches there are also rewards. A lot of this material is in her earlier book, Condors in Canyon Country, published by the Grand Canyon Association in 2007, now out-of-print (though available used). It’s presented here from a different perspective, both more personal and more scientific (those footnotes!). I am very happy Osborn decided to tell her stories again; enlightening, amusing, and educational, they also give insight into what it’s like to work as part of the Condor Recovery Project–the extended hours, physical labor, stress, and fun.

Osborn is a superlative natural history writer. She crafts her prose with a visual immediacy that bring you directly into her experience. She never finds her long days observing her falcons, crows, and condors boring. Every day is an adventure, and she describes the birds’ flights, fights, play, individual differences, developing skills, and environmental challenges in rich, elegant detail. She is also adept at communicating the dramas, small and large–her panic when Osiris the Peregrine Falcon disappears for twelve days; her amusement at a face-to-face scolding by Malama, the ‘Alala who appeared to remember that she had “tormented” him with malaria treatments; her fear when she discovers Condor 240 dead on private land, his tags and transmitters removed and buried, a strange person on horseback approaching. She is particularly talented at painting how birds fly and interact. Here is Osborn on observing the young Peregrine Falcons in the air while simultaneously recording their actions:

Evening and mornings were now filled with the falcons’ scream and aerial exploits as one bird streamed after another like a small fighter plane locked onto a fast-moving target. The pursued bird dodged and rolled, tucked its wings, and fell earthward in ever-more sophisticated evasive maneuvers. Becoming one with the sky, the peregrines flew with ineffable grace, dazzling speed, and breathtaking agility. As I watched their transcendent flights, I felt my own heart quicken. Transported by the falcons’ inimitable aerial prowess, I could almost feel the wind stream behind me, feel every subtle movement of wing or tail that determined my trajectory, my speed, my effortless engagement with the wind. All the while, earthbound, I dispassionately scribbled my field notes, recording our falcons’ flights while never taking my eyes off the birds as they traced invisible loops across the firmament, imprinting their movements, their exuberance, their vitality forever in my mind’s eye, and lifting my spirits in ways that only such epiphanic sights in nature can. (pp. 49-50)

She is also adept at writing about conservation’s larger context in terms of its history, public policy struggles, and the science behind species re-introduction. Well-researched and footnoted, these sections never feel disconnected from the more personal sections. She explains complex and sometimes controversial topics including captive breeding, environmental toxins, feral cats and other invasive predators, Hawaiian avian extinction, avian disease, California Condor distribution and history, legal loopholes, and lead poisoning. Familiar subjects to many of us, but ones that take on a new intensity when discussed in connection to birds that you feel you know. And we do feel like we know them, not as intimately as Sophie Osborn, of course, but stories create connections, especially when they are lively stories about birds with names and personalities. Osborn does a good job straddling the anthropomorphic precipice, always interpolating personality from actual behavior, never from her own psyche.

The extensive footnotes (36 pages, small print) are impeccably written and include scientific journal articles, government reports, websites, natural histories, and occasionally addenda to the text. There is also a very detailed, well-constructed index. The Notes and Index emphasize the serious conservation messages at the heart of Osborn’s stories, as do the two final chapters, “Condor in the Coal Mine,” an update to both Osborn’s life and the lives of her California Condors, and the “Epilogue,” a summary of the conservation challenges all birds and things natural face and the small and large ways in which we as birders and individuals can create change.

Author Sophie A. H. Osborn, photo by Lisa Koitzsch, © Sophie A. H. Osborn

Author Sophie A. H. Osborn, photo by Lisa Koitzsch, © Sophie A. H. Osborn

Chelsea Green Publishing, a company committed to “publishing as a tool for social change and ecological stewardship,” has done an excellent job designing and packaging Feather Trails. In addition to the extensive Notes and Index, sections are divided by full-length title pages featuring a silhouette of the subject bird, the silhouette is repeated on the first page of each chapter, the font is fairly large and very readable, and they used recycled paper. My only wish is that the book included photographs. There is a beautiful photograph of a Peregrine Falcon on the cover and smaller photographs of Hawaiian Crow and California Condor on the back cover, but I want more. I ended up looking for photographs of Peregrine hack sites, captive breeding aviaries, Hawaii tropical forest, and the California Condors of the Grand Canyon on the Internet. They weren’t hard to find, but I would have appreciated, if publishing them in the book is too costly, a small collection on the publisher’s web site. I hope they consider this idea for future books.

Sophie Osborn has a long history of observing, surveying, and studying birds in North, Central and South America as field biologist, research biologist, field manager, and wildlife program director. A couple of these stints (besides the three described here) are briefly described in tantalizing (and scary) detail in Feather Trails. (I’d love to read a book about your adventures in Guatemala studying Yellow-naped Amazons, Sophie!) She has a master’s degree in science from the University of Montana, and is the author, as mentioned above, of Condors in Canyon Country: The Return of the California Condor to the Grand Canyon Region (Grand Canyon Association, 2007), recipient of many awards including the 2007 National Outdoor Book Award for Nature and the Environment. She’s also written articles in scientific journals and nature/birding magazines and kept the public informed about the California Condor project with her many “Notes From the Field” for The Peregrine Fund newsletter. She also maintains a website of her writings on nature and conservation at Words for Birds.

Feather Trails: A Journey of Discovery Among Endangered Birds by Sophie A. H. Osborn is one of the best books I’ve read about endangered birds and conservation. It’s a subject that can easily veer into preachiness and depression. By focusing on three case studies from a personal, memoir-oriented point of view, Osborn engages our imagination while informing our brain. She illustrates the commitment and hard work of the field biologists and condor workers responsible for the successes of these projects. She makes the point that while much funding and public support goes to charismatic birds like Peregrine Falcon and California Condor, other birds on the brink of extinction, like the Hawaiian Crow, are barely known and funded and the complex work needed to return them to the wild may never be finished. She articulates additional problems biologists and conservationists are tackling–human garbage, wind turbines, and of course climate change, pointing out that while these seem insurmountable, analyzing the problem, pulling apart the threads, knowing the birds, learning their stories can be paths to hope. Sophie Osborn has a lot of stories to tell, a lot to say about the world of conservation biology and politics, and I hope she continues to write in her elegant style about both.

* Unfortunately, the Hawaiian diacritical character required to spell ‘Alala and Malama correctly cannot be inserted into this version of WordPress. I’m very upset and sorry about this and next time I write about Hawaiian birds I’ll ask our person-in-charge if there is a plug-in that will work.

Feather Trails: A Journey of Discovery Among Endangered Birds

by Sophie A. H. Osborn, Forward by Pete Dunne

Chelsea Green, May 2024, 384 pages

ISBN-10 : 1645022420; ISBN-13 : 978-1645022428

$29.95

What a great review! And what a fabulous and powerful book. I thoroughly enjoyed Feather Trails and recommend it highly. The writing is beautiful. The stories are captivating. The information conveyed is so important. This is a perfect blend of storytelling, research, memoir, science, and conservation. Sophie Osborn draws you into the world of protecting and restoring endangered species and sweeps you up into the trials and tribulations of a field biologist. Her writing is so evocative and her overwhelming message of hope in the face of so many difficult challenges is inspiring.

Very well done review. Thanks.