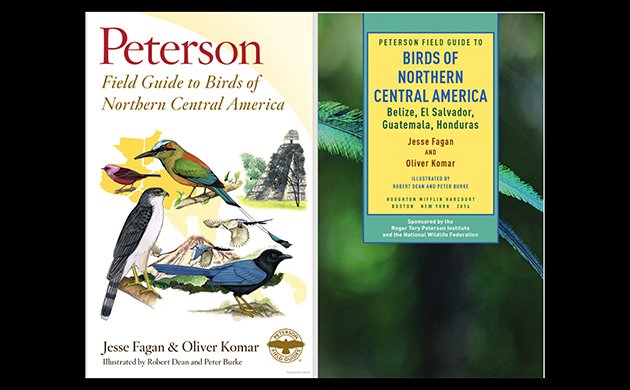

Birds know habitat. They don’t read treaties or draw maps or build walls and, as far as we can tell (since we can’t talk to birds, yet), they have no concept of political boundaries. So, if you are going to write a field guide on the birds of the countries south and east of Mexico–Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—it makes the utmost sense that you embrace the whole geographic area. The Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America by Jesse Fagan and Oliver Komar, illustrated by Robert Dean and Peter Burke, does just that. This book is a field guide treat for traveling birders and birders who love to fantasize about travel, answering that age-old question, “I’m going on a trip to [fill in the blank—Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras], what field guide should I use?”

It has been a long time between field guides for most of these countries. When I went to Honduras in 2014, I was advised to use The Birds of Costa Rica by Richard Garrigues and Robert Dean (2014) and The Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America by Steve N.G. Howell and Sophie Webb (a classic, but big and published in 1995). Robert Gallardo’s self-published Guide to the Birds of Honduras came out in 2015, and is the first bird field guide dedicated to that country. (I have not yet had a chance to examine Gallardo’s guide; I know it was a labor of love and a product of much hard work.) There has never been an English-language field guide written for El Salvador, the only Guatemala bird guide is 26 years old and out of print, and the bird guide for Belize is 13 years old. If there is a relationship between birding tourism and field guides, then The Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America will be a boon for the countries themselves as well as birders and bird touring companies.

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America covers 827 species, including resident, migratory, and common vagrant birds. Appendices list all vagrant species; “hypothetical species”—20 species reported by reliable observers but not well documented; and “more species to watch for in NCA”—20 species that should be showing up based on historical records, birds of neighboring countries and migratory patterns.

Species accounts are organized primarily on Clement’s Checklist (the taxonomy used by eBird), but it is noted in the Introduction that there are cases where other taxonomies are followed or species are re-arranged so similar looking species can be shown together. A fourth Appendix chapter, “Future Splits and Taxonomic Changes” explains which 2016 American Ornithologists Union taxonomic order changes the authors were able to incorporate, and not incorporate into the guide, which was on its way to publication. (This means, amongst other things, that Nightjars and Potoos are still between owls and trogons and not following cuckoos, which really seems more appropriate to me.)

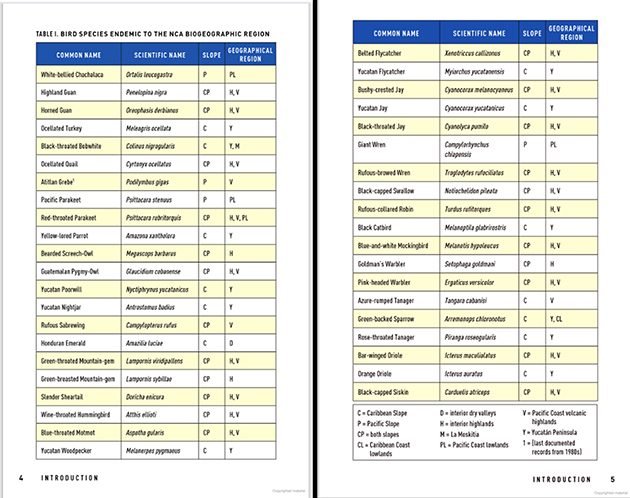

The brief, excellent introduction focuses on explaining topography and bird distribution in NCA (the abbreviation used throughout the guide, and this review, for Northern Central America). This is key to understanding what birds you may observe in the area. The first thing you learn on a birding trip to any country in Central America is the importance of the Continental Divide; there are two main and very different environments here—the Caribbean Slope and the Pacific Slope. And, then there are the geographic complications caused by the convergence of major tectonic plates (sections of the earth’s crust), which has created volcanic areas and distinct, separate areas regions defined by altitude, seismic activity, and climate. The end result is that the whole “biographic” area (NCA plus southern Mexico and northern Nicaragua) is home to 41 endemic bird species. These are listed in a table, which also specifies slope and geographic region (but not country).

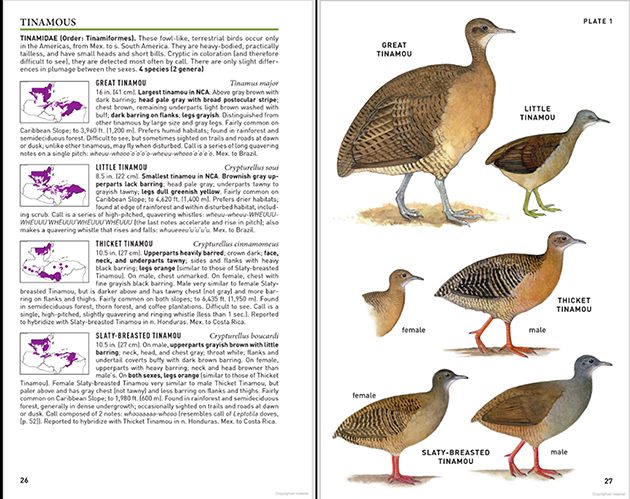

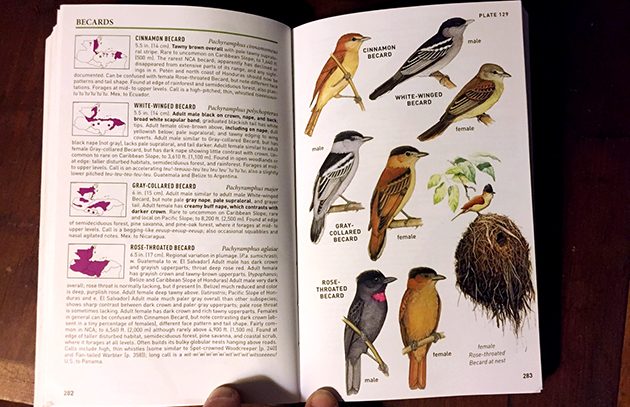

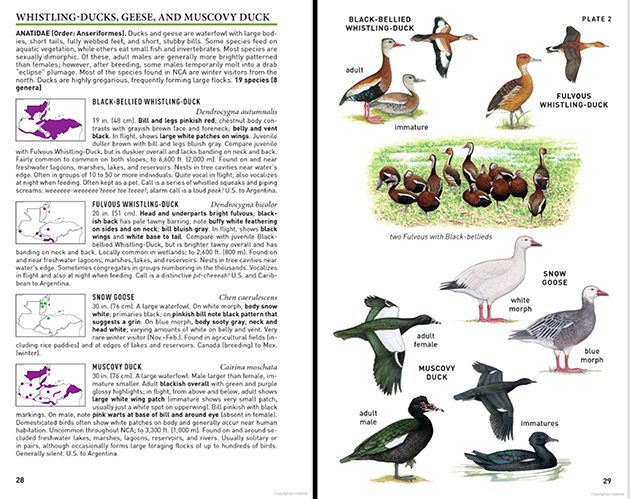

In the Peterson field guide tradition, text and range maps are on the left and illustrations are on the right (though, unlike the tradition Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America there are no arrows pointing to field marks). Each family group starts with a description of what traits are common to the species within the family, its representation in Northern Central America, and other interesting, relevant facts. Each species account lists the basics—common name, scientific name, measurements in inches and centimeters. A succinct but specific description of the bird emphasizes distinctive field marks, written in bold print, including, where appropriate, what the species looks like in flight. The authors specify plumages to be expected for NCA migratory birds, as well as plumage differences, if any, by gender and age.

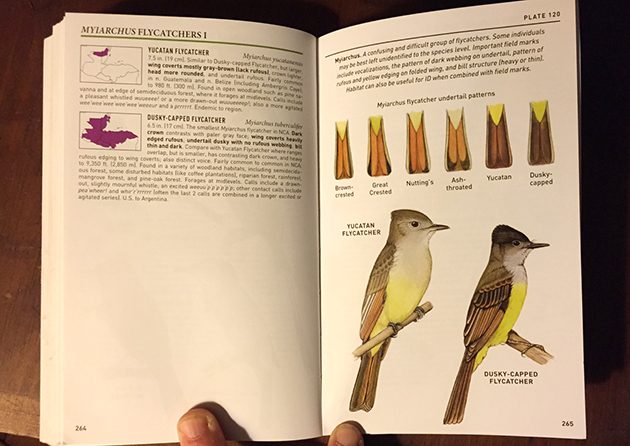

A lot of attention is given to differentiating amongst similar looking species. So, we find out that that White-fronted Parrot looks similar to Yellow-lored Parrot, except that White-fronted has red lores and lacks the dark ear patch. This is an important fact to keep in mind if you are birding Belize and northern Guatemala, where their ranges overlap. Notes on plates of notably confusing birds—sandpipers, flycatchers, the “virens warblers”—offer clues to sorting them out, with the caution that “some individuals may be best identified to the species level.” These exact words come from the section on Myiarchus flycatchers, but I couldn’t help hoping that the illustration of six Myiarchus species’ undertail patterns would help.

Attention is given to subspecies, with descriptions given for the varying plumages found in different areas of NCA. So, for example, we learn that the adult male Rose-throated Becard’s sumichrasti subspecies (western Guatalmala to western El Salvador) has a dark crown, grayish upperparts and a deep rose throat, that the adult male of the hypophaeus subspecies (Belize and the Caribbean Slope of Honduras) is very dark overall and often lacks the rose throat, and that the adult male of the latirostris subspecies (Pacific Slope of Honduras and eastern El Salvador) is paler gray than all other subspecies and has a pale rose throat, sometimes. A lot of information can be packed into a paragraph.

Species accounts also describe relative abundance; habitat in which the species is likely to be found (rainforest, coffee plantation, pelagic, urban parks, and nine principal forest types, described in the Introduction); behavior patterns useful for identification, and vocalization. A lot of attention is given to how vocalizations are articulated. For the most part, songs and calls are spelled out phonetically, with capital letters and punctuation symbols–exclamation points, apostrophes, hyphens, and dashes—used to indicate sharpness, loudness, and pauses, often in combination. It sounds a little confusing when explained in the Introduction, but makes a lot of intuitive sense when you sound out the calls themselves. Users are also encouraged to use media libraries and apps to hear vocalizations.

Range maps accompany each species account—small but specific. The map template shows the political boundaries of each country, and are color and shape coded to show permanent residents, nonbreeding visitors, breeding visitors, transients, vagrants, breeding colonies, local wintering sites, locally resident year-round sites, and suspected sites. This results in some colorful maps for species like Black-crowned Night-Heron that are both resident and migratory. The maps are useful for pinpointing if the species can be found in a specific country since the abundance and range descriptions focus on geographic habitat locations.

Robert Dean illustrated most of the 827 species described in this field guide. Peter Burke provided illustrations for the jaegers, several flight drawings of shorebirds, and over 100 illustrations that the authors call “vignettes”—drawings of flocks, birds in specific trees, birds at their nests (see the Becard plate above and the Whistling-Ducks below), birds engaged in courtship behavior. These vignettes are lovely and, besides providing additional visual information, give the plates movement and eye relief from the rigors of looking at bird, bird, bird, and another bird. (Don’t get me wrong, I love looking at all these birds, even the brown-on-brown species, but there is a repetitive pattern here.)

Robert Dean is a former British musician and now wildlife illustrator who lives in Costa Rica; he has illustrated The Wildlife of Costa Rica: A Field Guide (2010), The Birds of Panama: A Field Guide (2010), The Birds of Costa Rica: A Field Guide (2007, 2014), and the forthcoming Birds of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curacao: A Site and Field Guide. I took a look at the 2nd edition of The Birds of Costa Rica; many of the illustrations there are used in the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America, only they look better in the NCA book. With fewer birds on each plate, the images are larger in size. The font used to label the birds is bolder and larger. The color is also different for some images, in most cases slightly deeper (nightjars, trogons) but for some images slightly lighter (White-throated Magpie-Jay).

Some images have been redone. Keel-billed Motmot, for example, has been re-colored to reflect the rufous underparts of Northern Central America, as opposed to the greener tones of the Costa Rica bird; similarly, the Rose-throated Becard of the NCA guide shows off its deep red throat, the Costa Rica race’s throat is all gray. And, of course, there are those species not found in Costa Rica like Yucatan Flycatcher and, of course, Honduran Emerald (endemic to Honduras); I’m assuming that these images were created for this guide.

I like Dean’s images for their attention to detail and clean lines. Even his Empidonax flycatchers are individually distinct. However, they don’t always convey the beauty or grace of certain species. His Agami Heron is just another heron, not the stunning creature of iridescent colors that steps carefully through wetlands; his Black-crested Coquette is a rather stubby, funny looking hummingbird, not the glamorously plumaged tiny bundle of energy I saw in Honduras. Of course, this is an identification guide, not a coffee table book. And, his renditions of many other species, especially those like trogons that are more sedentary, are excellent.

Jesse Fagan and Oliver Komar are the ideal combination to write a field guide, complementing each other in background and skills. Fagan is a professional bird guide with Field Guides, Inc., where he leads tours to the countries covered in the guide as well as South America, Europe, and other wonderful birdy areas of the world. He currently lives in Peru. Oliver Komar, originally from Newton, Massachusetts, is professor of natural resources at Zamorano University, Honduras, but has spent much of his professional life in El Salvador. According to an article in Audubon Magazine, Komar documented “nearly 45” new species there, initiated conservation projects, and worked with Birdlife International to identify the country’s 20 Important Bird Areas.

This is a small, light field guide that will comfortably fit into a large pocket or small backpack. It is a paperback, not flexibound like the North American Peterson guides, which may lead to a very worn cover. But, then again, most of us will only be using this field guide for a limited amount of time.

Species can easily be found using the Quick Index on the inside front and back covers. There is also a more comprehensive index listing species by common and scientific name, with illustration pages bolded. I do wish that the political and physical maps of NCA and the map legend for the color coded range maps, all presented within the Introduction, were also printed in the inside back and front covers. If I were to use this book in the field, I would need to put tabs on these pages.

There are no checklists, and I found this puzzling. As I said in the beginning of this review, I understand the concept of combining four countries united by a common geography into one field guide. But, most of us birders will be visiting a country, a political region, and will want to know what birds we will hopefully observe within those political boundaries. The authors encourage birders to use eBird to improve the accuracy of birding site checklists and bar graphs, but, as far as I know, you cannot generate country checklists from eBird. Any insights into why country checklists were not included in the field guide (too many pages which would add to the weight and cost is what came immediately to my mind) will be appreciated.

The Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America is an up-to-date, comprehensive, much needed field guide; it is reasonably priced (especially when you consider it covers four countries), efficiently organized, well illustrated, and packed with as much high quality information as is possible to load into a compact guide and still maintain its readability. It really is an achievement. Perusing this book makes me want to bird Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras (again) NOW. And, I hope a lot of birders feel that way. Honduras has become a very popular birding destination in recent years, but Belize, Guatemala, and El Salvador could benefit from increased birding tourism. There is definitely a relationship between good field guides and birding travel. And, it’s good to see the people behind the Peterson Field Guide series recognize this, expand their borders, and embrace two excellent field guide authors.

Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America (Peterson Field Guides)

by Jesse Fagan and Oliver Komar (Authors), Robert Dean and Peter Burke (Illustrators)

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, November 2016, 448 pages, 4.5 x 1 x 7.2 inches.

ISBN-10: 054437326X; ISBN-13: 978-0544373266

$25.00 (with discounts from the usual suspects)

I have seen a strange looking bird of prey in a barn in Chessnee SC USA – I have never seen one with the tail feathers like this one . It’s young . Seen Dec 1 2018 I need to send the pic if it

I strong suggest that field guides should have local names, no just English common names. It is help when the observer want to ask the local people for determinate specie . It is sometimes make more difficult communication between us and village people. The most species has a indigenous name in Quiche , Maya language as Spanish names.

Will this book be good for the Yucatan Peninsula? Specifically Quintana Roo?