As devoted readers of 10,000 Birds know, the writers contribute checklists to a joint eBird account called the “10,000 Birds Collaborative.”

Every month, Redgannet summarizes the checklists, providing an updated life list, year list, and country list. For the United States, there is also a state list. The Collaborative has a profile page that, like all eBird profile pages, suggests some goals.

This post updates the numbers from three years ago. Although the Collaborative list is a global one, this post focuses on the U.S. submissions.

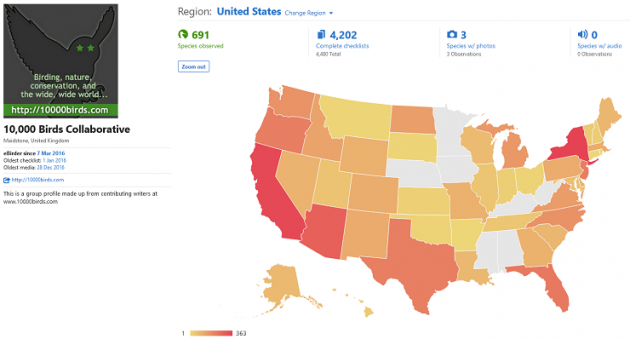

As of mid-November 2021, the Collaborative had submitted more than 4,200 checklists (up from 1,700 in 2018) and has observed 691 species in the United States (up from 618). The Collaborative has also added six states. Here is the updated eBird heat map:

Unsurprisingly for a site founded and run by two New Yorkers, the Empire State still boasts the highest number of species (363, up from 316). Not far behind is California (348, up from 297), followed by Arizona (294, up from 155), Florida (233, up from 227), New Jersey (223, up from 199), Oregon (221, up from 209), and Texas (218, up from 106). Thus, there are now seven states with 200+ observed species. The state with the largest increase was Arizona, with 139 species added.

Many of the states with more than 200 species are home to contributors and/or have destination birding locations and/or are popular places generally. Some are all three (e.g., New York, California, and Florida).

There are several states with 100-199 species: North Carolina (172, unchanged), Washington (171, up from 144), Michigan (159, unchanged), Virginia (147, up from 122), North Dakota (141, unchanged), Idaho (129, up from 57); New Mexico (112, unchanged); Massachusetts (110, up from 81); Colorado (106, unchanged), and Pennsylvania (109, up from 102). Two of these are new to the 100+ list. (Inexplicably, eBird does not consider Puerto Rico part of the United States, but if it were properly included, it would do well, with 107 species.)

However, most states still have less than 100 species, including: Missouri (98, unchanged); Wyoming (97, unchanged); Georgia (94, up from 54); Nevada (93, up from 53); Delaware (88, up from 83); Maine (82, up from 76); South Carolina (82, up from 49); Louisiana (81, up from 73); Alaska (79, up from 34); Maryland (62, unchanged); Illinois (50, up from 2), Tennessee (46, up from 17); Vermont (34, unchanged); New Hampshire (34, up from 31); Indiana (27, unchanged); Kansas (23, unchanged); Ohio (16, unchanged); South Dakota (14, unchanged); Montana (11, unchanged); and Arkansas (8, unchanged).

The Collective added six new states in the past three years, but none have eclipsed the century mark: Wisconsin (74), Utah (55), Hawaii (38), Oklahoma (18), Rhode Island (9), and Connecticut (5).

A few states still have no checklists at all: Nebraska, Minnesota, Iowa, Kentucky, West Virginia, Mississippi, and Alabama. Even the nation’s capital has been ignored. Many of these “missing” states have few checklists overall, so the Collaborative is fairly representative in that respect. For example, as to checklists, Kentucky ranks 37th in the U.S. (out of 51, including Washington, D.C.) and West Virginia ranks 44th. In contrast, the Collaborative has checklists from all but one of the 20 states with the most checklists, the exception being Minnesota.

Many of these “missing” states are in the Midwest or South, far from most of the writers. Thus, like all things relating to real estate, the most important factor is location, location, location.

Naturally, the “missing” states implicitly suggest birding trips, as every “empty” state provides excellent birding opportunities. For example, my list of the Top 25 National Wildlife Refuges for birding includes an excellent location in Minnesota (Minnesota Valley NWR).

Birding provides endless opportunities to see birds in their varied habitats across the United States (and the world) and the writers of 10,000 Birds will surely enjoy filling the remaining states on the map. However, at 691 species already observed, new species will be relatively rare going forward.

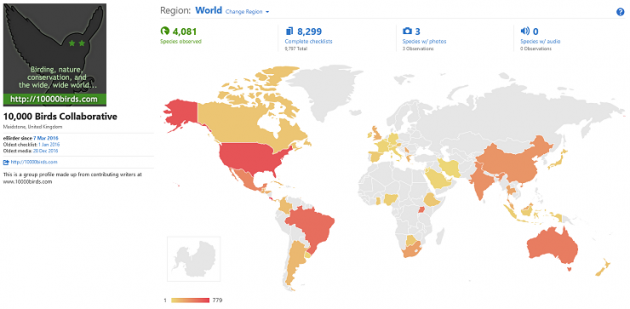

Of course, the Collaborative will also continue to work on the global map as well. (The map would look a lot more complete if someone added a checklist from Russia.)

I love this analysis, Jason. Plus, I just added a new species–Painted Bunting–to our New York list this morning!

I always think of something I should have included when I see a post actually published. As to the diminishing rate of observations of new species, there was an approximate 150% increase in checklists submitted and an approximate 12% increase in species. I’m confident that ratio will continue to decrease, a phenomenon familiar to all birders.

Get this pandemic to go away, and I promise to add Turkey, Jordan, and Morocco to the countries represented ASAP. Of course, if we had gone through with our travel plans in March of 2020, I might be stuck writing my posts from Turkey or Jordan still.