Congress overwhelmingly passed (310-107 in the House and 73-25 in the Senate) and President Trump signed the Great American Outdoors Act, a rare bipartisan conservation achievement in a bitterly divided Washington D.C.

A key aspect of the bill — and much of the coverage — has revolved around fully and permanently funding something called the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF).

What is the LWCF and why does it matter to birders?

* * *

The Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 was enacted to preserve access to outdoor recreation, and it created the LWCF as a funding source. Broadly speaking, LWCF has been used for three purposes:

-

- It is a key funding source for land acquisition by four federal agencies—the Forest Service (FS), National Park Service (NPS), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and Bureau of Land Management (BLM);

- It provides “financial assistance to states” via a matching grant program to assist states in planning, acquiring, and developing outdoor recreational facilities;

- It has been used fund other federal programs with natural resource-related purposes.

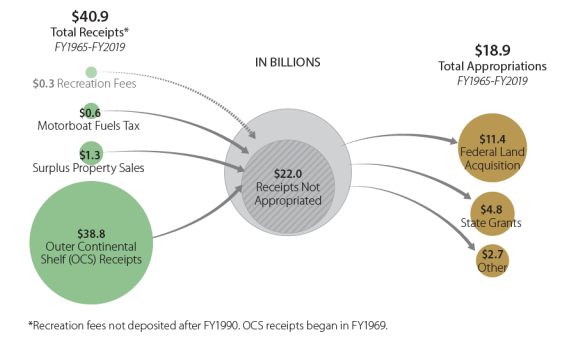

The LWCF fund is authorized to accrue $900 million annually from several sources, though historically nearly all revenue has come from oil and gas leasing in the Outer Continental Shelf.

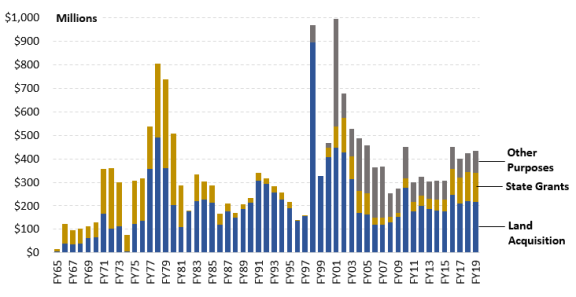

However, the accrued money is not actually spent unless Congress appropriates funds. Congress determines the level of funding through the annual appropriations process and that process has substantially reduced the funds available for conservation. In fact, less than half of the $40.9 billion in total revenues that have accrued in the LWCF have been appropriated ($18.9 billion), leaving an unappropriated balance of approximately $22.0 billion.

In other words, Congress has appropriated less than half of the money accrued for conservation, siphoning it off for other purposes.

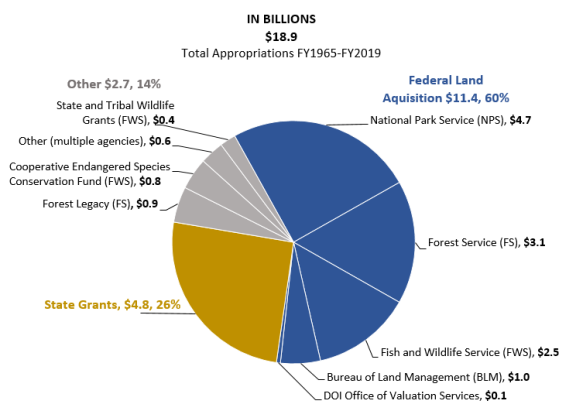

The $18.9 billion that actually has been appropriated has been allocated for federal land acquisition (60%), state grants (26%), and other purposes (14%). The federal land acquisition funds have been allocated unevenly among the four agencies, significantly favoring the NPS, as shown below.

For a sense of magnitude, the approximately $11.4 billion in LWCF appropriations since the 1960s is substantially more than the approximately $1 billion of Federal Duck Stamp revenue since the 1930s. In other words, despite receiving little publicity, the LWCF has financed the vast majority of federal land acquisition for conservation.

The LWCF is generally considered a key land acquisition tool for both the federal government and states, and it has broad support in the conservation community. More than 800 organizations signed a letter supporting the Great American Outdoors Act, including many conservation organizations, as well as groups representing hikers, fly fishers, hunters, bikers, off-roaders, and RVers, among others.

What sort of land is obtained with LWCF money? The LWCF Coalition maintains state-specific datasheets that identify federal and state projects that have received LWCF funding, though the sheets do not disclose specific amounts.

For example, since inception of the LWCF program, Oregon has received approximately $335 million, with funding going to countless projects, including notable birding hotspots such as Malheur NWR, Tualatin River NWR, and refuges in the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex. (Find your state via this link, and here are California, Texas, New York, and Florida.)

Simply put, virtually every birder has surely birded on land that has benefited from the LWCF.

The Great American Outdoors Act would also create a new $9.5 billion fund ($1.9 billion/year for five years) to address deferred maintenance projects for NPS, FS, FWS, and BLM. To use Oregon as an example again, NPS reports deferred maintenance of $100,440,129 just at Crater Lake NP. Thus, the Act would also begin to address a huge maintenance backlog for our federal public lands, with the bulk of funds going to the NPS.

From a birder perspective, the Great American Outdoors Act will substantially and permanently increase the amount of LWCF funding for land acquisition by the federal government, states, and tribes. That money will go to land for conservation and recreation, which will provide habitat for birds and places for birders to observe them. Funding will be set at $900 million per year, far more than has generally been appropriated in the past. (The Trump Administration had previously proposed slashing funding for the LWCF.) And the Act will help address the maintenance backlog on federal public lands, particularly the spectacular National Parks.

For birders, this is a very good development during an Administration where there have been very few such developments.

This post was originally published on July 24, 2020, and has been updated.

* * *

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) provides non-partisan research and analysis to members of Congress. Its excellent report on the LWCS (dated June 2019) is a primary basis for this post and the source for the figures above. The top image is Buenos Aires NWR in Arizona.

While I completely and totally applaud this funding, it will not be close to enough. We are going to need an equivalent Marshall Plan funding encompassing public and private on an International scale we have not begun to fully think of yet.

TNC, WWF, DU, basically everybody will have to come together at the international level to initiate- not talk about- how to reverse widespread ecological destruction while ongoing education campaigns are undertaken.

We’ve missed the first deadlines.

This seems like a great conservation bill, especially since much funds will go to the NPS, which has always been the most underfunded and benign agency (in relation to wildlife) within the Dept. of Interior. But there’s a flip side which was not mentioned. The source of most funds will come from the royalties of the big oil and gas industries. Something wrong with this picture? Promoting climate change to save species from climate change? Another is “recreation,’ and “tourism.” We need less human activity on public lands, not more. The fact that Trump signed this bill with enthusiasm sends a shiver down my spine.