Sometime in early modern history, European haute cuisine lost its appetite for spice. After centuries of hungering for the rarest and costliest of aromatic seasonings imported from the East – brought to market over thousands of miles by caravel or baggage train to be sold at kingly prices – wealthy Europeans began to fancy their food without that once-luxurious dusting of nutmeg, ginger, clove, and the like.

Ship-to-table: A spice-laced medieval feast from the Grandes Chroniques de France of Charles V.

Much of this monumental shift in taste originated with a culinary revolution that took place in 17th-century France, when ancien régime chefs like La Varenne and Massialot led a retreat from the heavily spiced fare of the medieval table, turning instead to fresh local herbs like thyme, chervil, and parsley for flavor (as well as an impressively codified repertory of sauces). Around the same time, wines came to be prized for expressing the natural characteristics of the grape through the alchemy of fermentation and aging, without masking infusions of sugar and spice that often adulterated wine in earlier times. And in brewing, bitter hops had almost entirely replaced a heavily taxed (and therefore Church-endorsed) concoction of spices, herbs, and roots known as gruit as the flavoring of choice for beer. At dining tables across Europe, there was a move toward embracing lighter, more subtle flavors over the archaic, overly spiced palate of the past.

The title page of Le cuisinier françois by François Pierre La Varenne, a watershed cookbook in European history.

But old habits always die hard, and vestiges of Europe’s ancient spice obsession remain with us centuries later, resurrected annually in the festive food and drink of the Western holiday season. Because of their great expense, spices in the Middle Ages were often reserved for feasts celebrating harvests, slaughters, and holy days as the old year waned, particularly around Christmas. In our own times, the plague-like pumpkin spice hysteria that descends upon us every autumn – and which shows no signs of ebbing as we near the third decade of the century – is but the most evident continuation of this custom. And while most people realize that pumpkin spice contains no gourd or squash of any kind, its constituent seasonings – typically cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and clove – carry on a venerable tradition of motley spice blends in European cuisine. In the British Commonwealth, a nearly identical product called mixed spice is popular for holiday baking, sometimes known as “pudding spice” owing to its obligatory use in traditional Christmas desserts. And a Dutch blend called koekkruiden is much loved in treats made for the celebration of the Feast of Saint Nicholas on December 6th. As seasonings for meat, fish, and vegetables, spices like cloves and mace fell out of fashion along with doublets and ruffled collars, but these imports from the steamy island forests of southeast Asia remain popular to this day – with some irony – in flavoring dark and sticky treats best enjoyed fireside in the dead of the northern winter.

Gingerbread birds: Speculaas cookies are prepared in the Low Countries to celebrate Saint Nicholas (Sinterklaas) on December 6th.

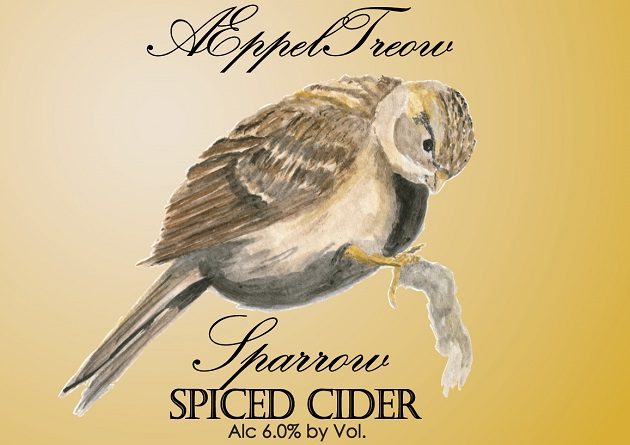

Such are the flavors that imbue this week’s featured tipple, the Sparrow Spiced Cider by Æppeltreow Winery and Cidery of Burlington, Wisconsin (we’ve featured ciders from Æppeltreow’s “Songbird Draft Cider” series twice before, their Kinglet Bitter Draft Cider and Barn Swallow Draft Cider). As the folks at Æppeltreow surely understand, adding a good dose of sweet spice to any brew is foolproof way to invoke the holiday spirit, whether it’s in mulled wine, wassail, eggnog, glühwein, or a spiced bière de Noël. Like gingerbread and fruitcake, these celebratory drinks are culinary relics of a sort, inherited from a spice-obsessed past of possets, syllabubs, flips, and other curiously named beverages of yore. And while holiday spices once commanded prices commensurate with gold and jewels, these now-commonplace ingredients feel almost quaint and soothing – and forever linked with the Christmas season (and Hanukkah, too – what would kugel be without cinnamon?). In fact, their flavors invariably seem out of place at any other time of the year, even in the long months of winter to come in the new year. No one ever really craves holiday spices in January, do they?

There’s no doubt that the ancestry of Æppeltreow’s Sparrow Spiced Cider can be traced to the mulled drinks of the Middle Ages, but the identity of the bird on the label is more uncertain. It’s not an obvious likeness of any species in particular, but I think most birders would identify the drab bird appearing on the label as a familiar House Sparrow. There’s no obvious reason for its selection here, but perhaps – as one of the most infamous and widespread invasive birds in the world – it’s a reminder of the forces of trade and colonialism that brought both spices to Europe, and European birds to the Americas and elsewhere, for better or worse. Or – reading into it all a bit less seriously – perhaps we could interpret the House Sparrow as a reminder of the cozy and comforting domesticity in which we’re usually coddled and swaddled around the holidays, whether we like it or not?

Cinnamon bird: A female Russet Sparrow (Passer cinnamomeus).

There’s a third, more attractive identification, however, which I prefer: The bird in questions might not be a House Sparrow at all, but rather a Russet Sparrow (Passer cinnamomeus), a lookalike relative from East Asia that even comes with an appropriately spicy specific epithet (try saying that five times fast!). True, the name cinnamomeus refers to the reddish-brown plumage of the male and has nothing to do with the spice harvested from Cinnamomum spp., though there probably is some range overlap between bird and bark. And as unlikely as it seems that a cidermaker in the American upper Midwest would choose this species, I think it makes a fitting mascot for this spiced cider.

A pair of Russet Sparrows, as illustrated by Philipp Franz von Siebold in Fauna Japonica. Or, to give its full title: Fauna Japonica sive Descriptio animalium, quae in itinere per Japoniam, jussu et auspiciis superiorum, qui summum in India Batava imperium tenent, suscepto, annis 1825 – 1830 collegit, notis, observationibus et adumbrationibus illustravit Ph. Fr. de Siebold. Conjunctis studiis C. J. Temminck et H. Schlegel pro vertebratis atque W. de Haan pro invertebratis elaborata.

While the true identity of our sparrow remains a guess at best, there’s no ambiguity about the spicing of this shimmering, amber cider from Æppeltreow: the unmistakable aroma of cloves, cinnamon, and a bit of peppery white cardamom standing front and center (according to the cidery, mace, cinnamon, star anise, and cardamom were used to brew this cider). Æppeltreow used a blend of modern and heirloom apple varieties for this cider (Red Delicious, Cortland, McIntosh, and Greenings) and the resulting palate is pleasantly sweet and sour, tasting of spicy mace and apple dumplings, with a tannic, slightly tart finish. Even when enjoyed slightly chilled at a good cellar temperature, this cider is instantly warming, undeniably dessert-like and redolent of the holidays – providing all the delights of a mulled holiday cup of cheer without waiting for it to cool enough to sip, or rummaging around the dark corners of one’s spice cabinet for that jar of mace.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Æppeltreow Winery & Cidery: Sparrow Spiced Cider

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Three out of five feathers (Good).

Leave a Comment