It’s been a rough year for Michoacán, the state in which I live. The state government has now announced plans for cloud seeding, in the dubious hope of producing some March rains. Our grass and forest fire season has already kicked in, some two months earlier than in normal years. And on Monday, February 5th, something extraordinary happened: The Morelian skies turned brown with smoke from… a lake, that was on fire.

This photo, which was shared on a local birders’ WhatsApp group, shows the enormous extension of burning reedbeds on that very windy day. And the large flat area in the foreground may look like a lake full of water, but I can assure you that it is bone-dry.

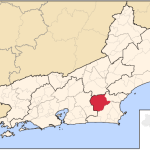

In a good year, Lake Cuitzeo is a major wintering ground for hundreds of thousands of waterfowl and shorebirds. And after visiting these birds regularly for the past ten years, I take their situation very personally. So it was frustrating when travel and other obligations kept me from checking in on them in throughout our very dry fall months. When I finally could go, on February 12th, I knew it would be useless to visit the area shown in the above photo. Instead, I went to the lake’s eastern end, where most water flows into the basin, and some water remains even in the driest of years. Would that still be true, this year? And would those birds still be there, or had they been forced to move on?

It’s a one-hour drive to my starting point of Araró, and the road beyond that town is a tiresome hybrid of asphalt and potholes. So I was very thankful to see that my efforts had paid off. The area west of Araró does indeed hold a remnant lake, as of February of 2024. (A recent local news article says its current maximum depth is 60 cm/2 feet, although I didn’t test this statement.) And this remnant lake is very, very birdy:

The dominant birds, besides those American White Pelicans seen at the right, were Northern Shovelers — hundreds of them. This was encouraging, because I had recently seen Blue-winged Teals, Green-winged Teals, American Wigeons, Gadwalls and Canvasbacks on smaller bodies of water in the area, but these were my first Shovelers for the season. And when I got home, photos I had taken of a flock flying overhead revealed Northern Pintails, another previously missing-in-action species.

I had not expected to determine the whereabouts of a a remaining duck species, the adorable Ruddy Duck. I normally see Ruddy Ducks on the lake’s deepest waters, and as I said, there are no deep waters in the Lake Cuitzeo right now. But at home, I was able to manipulate a few photos of the nearest mid-lake waterfowl, and those revealed the two-toned faces of winter Ruddy Ducks. It’s so good to see all my old friends are still around.

In passing, I should mention that winter Ruddy Ducks are cute, but it is the summer male that earns them the word “adorable”. “Goofy” and “designed by committee” would work, too:

Prior to this trip, my 2024 situation for shorebirds seemed even worse that the situation for waterfowl. In fact, the only shorebirds I had seen in other sites were Killdeer, which can occur far from water, and the Spotted Sandpipers that had turned up around smaller bodies of water. But the remnant of Lake Cuitzeo seemed to have many, if not most, of the other normal winter shorebirds for our region. There were lots of Western and Least Sandpipers, as one would hope. American Avocets and Black-necked Stilts also enjoy shallow water, so they were abundant. But there was also a fair number of Long-billed Dowitchers and Stilt Sandpipers, two similar-looking species that I wasn’t sure I’d see. Best of all, I got to enjoy five fantastic Long-billed Curlews.

Long-billed Dowitchers

Stilt Sandpipers, flying above Ring-billed Gulls and Northern Shovelers

One of those Long-billed Curlews, caught in flight

Of course, there were also Coots, Gulls, Terns, and lots of Herons and Egrets around. But it was two more species that made my day complete. On my way home, I decided to drive by Lake Queréndaro, a mid-sized lake to the south of Lake Cuitzeo. This lake is often choked with Water Hyacinth, and rarely offers more than American Coots, Pied-billed Grebes, and a collection of Grebes and Herons. But this time, the Water Hyacinths had been mostly cleared away, just in time for the lake to be the one source of deeper water for many miles around. Which meant that the Clark’s Grebes, now absent from Lake Cuitzeo had a place to stay:

And as a final treat, while standing on a bluff overlooking Lake Queréndaro, an American Bittern flushed from the shore just below, and flew so close that I barely managed to focus my camera before it disappeared in plants a bit farther along. This is a bird that loves to stay hidden, so it was a great encounter. I only managed one well-focused shot, but it’s a good one.

Next week, I’ll show you some of the more terrestrial birds that are also finding a way to survive my lake’s partial disappearance.

Paul, I was apprehensive when I started reading this post, but thank goodness it turned out well and the water birds have somewhere to stopover this year. Ominous times, but thanks for the happy ending— we need all we can get.

Saludos, Laura