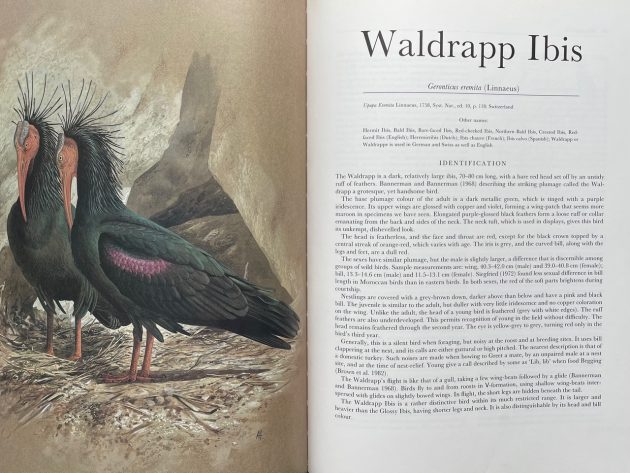

There’s something wonderfully primeval about the Northern Bald Ibis: it has the look of a bird that really ought to be extinct. The fact that it’s not is quite surprising, as this curious bird has come very close to the brink. According to Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World, a handsome volume written by James Hancock, James Kushan and Philip Kohl and published by Academic Press in 1992, Geronticus eremita “once nested in the mountains of central Europe, across northern Africa and into the Middle East. But this range is now much reduced. Nesting is now confined to Morocco, irregularly in Boghari in Algeria and in Birecik, Turkey.” (The image below shows Alan Harris’s evocative illustration of a pair of Bald Ibises, specially painted for Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World.)

Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills goes on to give greater detail of the former nesting sites in Europe: it could once be found “in southern Germany and Austria, in the valleys of the upper Rhine and Danube Rivers, and in the Alps of Switzerland, Italy and Germany, and perhaps in Hungary and Greece”. There’s no information as to when these European colonies died out, but we do know that it was a long time ago. Sadly, they no longer breed in Algeria, while in Turkey no free-flying birds remain. (In 1890 an estimated 3,000 pairs nested in Birecik.) The Moroccan colonies hold the last surviving wild birds, and even here the story has been, until recently, one of continual decline. Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World states that “disturbance by local people, tourists, and egg and zoo collectors has similarly reduced the colonies, and more protection is vital”.

Fortunately for the ibises, that protection did eventually come, and today the number of birds in Morocco is rising steadily. Conservation efforts have been sufficiently successful for the bird’s status to be downlisted, in 2018, from Critically Endangered to Endangered. BirdLife accompanied this change of status with a note that the “Wild colonies in Morocco are doing so well that the population is on the rise.” I haven’t managed to discover the latest population figures for Morocco, but it must be close to 1,000 birds.

Intriguingly, there are far more Bald Ibises in captivity than there are in the wild, for this is a bird that breeds readily in confinement. In 2018, there were 1,745 birds living in 92 different zoos and collections. I saw my first-ever live Bald Ibises in Jersey Zoo 40 years ago, but it wasn’t until 1997 that I finally saw wild birds in Morocco, near Agadir. They were my target species, and I remember being delighted in not only seeing them well, but finding feeding flocks that were remarkably unconcerned about being watched. I suspect that it is this lack of wariness that, historically, has been this bird’s downfall.

Today you no longer have to travel to North Africa to see Bald Ibises living in a wild state, thanks to exciting reintroduction projects in Europe. The most ambitious of these aims to establish a migratory population breeding in Austria and wintering in Italy. The EU-funded LIFE+ project, called Reason for Hope, is coordinated by the Austrian association Förderverein Waldrappteam, and is claimed to be the first science-based attempt to reintroduce a migratory species to its area of origin. The project aims to restore the migratory route of the Northern Bald Ibis from the breeding quarters in Germany and Austria to the wintering area in Tuscany.

The ibises were initially trained to follow a microlight aircraft over the Alps. The Italian wintering grounds are the WWF Oasis Laguna di Orbetello, where in February 2016 I was delighted to meet the flock. Despite the fact that efforts are made to ensure they are not imprinted on humans, they are naturally confiding, even friendly. The individual I am pictured holding (above) was a friendly bird that (rather like a dog) seemed happy to be handled. Such an intimate encounter with one of the world’s rarest birds was a memorable experience. Shooting remains a major threat to this population, for the Italians are still passionately keen on hunting. As long as the birds remain within the confines of the Laguna they are safe, but they are very vulnerable once they wander outside, and especially so when migrating to and from Austria. Many have been shot since the project started, despite a great deal of publicity raising awareness of the birds.

Meanwhile, away to the west in southern Spain, there’s another reintroduction project that is trying to establish a permanent, stable and self-sufficient colony in the area of La Janda, on the Atlantic coast near Cadiz. It is run by Zoobotánico Jerez in collaboration with the Spanish Ministry of Environment. The first reintroductions took place in 2003, and in 2008 some of the released birds started to nest on a cliff just outside the town of Vejar de la Frontera, where I’ve been lucky enough to see them, and where most of the photographs accompanying this piece were taken (in April 2019 and February 2024).

Bald Ibises are curious birds, for they are happy breeding in close proximity to man. The nesting cliff is at La Barca de Vejer, bordering a busy road, the A-134. It looks a most unsuitable location, but the birds clearly like it, and it remains their main breeding site. It’s easy to see them, for there’s an observation hide (built with funding from Red Eléctrica de España) on the opposite side of the road to the nesting cliff, and the site is marked on many maps. You can park your car close by, opposite the Restaurante Venta Pinto. I haven’t eaten there, but its popularity suggests it must be good.

The birds are early nesters, and when I visited Vejar earlier this month there were at least 30 birds crowded onto the nesting ledges. They are early nesters, but I was unable to tell whether any pairs already had eggs, though I suspected that some might have done. Photography is challenging as the cliff faces north-east and only receives the early morning light, so if you want to try and photograph them, go early.

La Barca de Vejer is close to the Barbate river, and the nearby Barbate Marismas provide feeding areas for the ibises. On a visit in October 2022, I found ibises feeding with cattle in scruffy roadside paddocks adjacent to the marismas (photographs below). Here they were easy to overlook. They can also be seen elsewhere in the area but particularly on the pastures along the A-2231 coastal road towards Zahara, and on local golf courses. There are now two other breeding sites, in addition to La Barca de Vejer, while the most recent figures I’ve seen suggest that there are around 25 breeding pairs and about 90 birds in the wild. Apparently they move relatively little, always staying in the vicinity of the region of La Janda.

Incidentally, the first part of the scientific name of this ibis, Geronticus, means old man, reflecting the fact that this ibis is bald, just like an elderly human. It’s a species with numerous alternative names, of which the commonest is Waldrapp, the name used in Germany and until recently, commonly used in English. It’s also called the Hermit Ibis, the Red-faced Ibis, the Crested Ibis and the Bare-faced Ibis. Whatever you want to call it, it’s a fascinating bird. It may not be beautiful, but it’s a bird with definite charisma. The fact that we can once again watch these remarkable birds in Europe is something to be celebrated.

There was a ringed (and thus individually identified) Northern Bald Ibis from the Austrian introduced population near Heidelberg that hung around for a number of months and that I went to see a few times. Heidelberg Zoo also has breeding Northern Bald Ibises. Such a charismatic species!

What I’ll never understand, for the life of me, is why they chose trigger-happy Italy as the wintering grounds for the Austrian population. I went to Tuscany a few times on holidays, and during one stay we happened to be there at the onset of hunting season. The soundscape was that of a war zone. So many shots were fired in such a short time that one got the impression of listening to machine guns. Ironically, it wasn’t 15 minutes into the shooting that the first ambulances could be heard. A shocking and eye-opening experience.

I can confirm that the Venta Pinto is excellent. Unless pressed for time or by the he demands of birding, I invariably pause here for a coffee & snack. I always take my binoculars with me not so much as a security measure but more to signal why I’m there. I am sure birders bring in extra trade. I’m told that the locals are very proud of “their” birds. Some years ago,

I wrote a blog about the species’ history in Spain which may be of interest. https://birdingcadizprovince.weebly.com/cadiz-birding-blog/bald-ibises-in-spain-the-historical-context

A fascinating article about a wonderful bird. Thank you David. Here’s to the bald old men !

Venta Pinta does have good tapas.

Is the hide new?

Amazing!

I’ve got a question, how many eggs does the Waldrapp lay and what is the chick survival rate (In the wild) ?

My friend identifies any bird quickly and accurately. He is a hunter who will not shoot the “wrong species”. He also has one good eye. How can you shoot a protected species that’s so recognisable with two good eyes? Malice.

Peter, I come from a hunter family, although I don’t hunt myself. Nothing wrong with responsible hunting. What we witnessed in Italy had nothing to do with hunting. That was slaughter by the sound of it.

I’ve been involved with shooting (or what most people call hunting) all my life, so though it’s a long time since I last got my gun out, I’m not against shooting. In Italy the ibises were shot by idiots who either didn’t bother to identify their target, or couldn’t care less about what they shot. I was told when I was in Italy that in at least one case, the shot bird was simply left where it fell. You can find reports about the shot ibises on the internet.

Ironically, perhaps, the ibis project has received sponsorship from the Italian hunters.