Indeed, archaeologists have found large numbers of bird mummies in catacombs in Egypt, particularly of ibises and falcons. These birds were regarded as sacred and worshiped in many parts of Egypt as they were considered to be the living incarnations of their respective gods (source).

Apparently, this was a complete industry, with animal keepers, embalmers, priests, as well as laborers building the cemeteries. Pilgrims bought animals specially bred at these centers. The birds would be killed by priests, mummified, and placed in a catacomb or cemetery as a gift to the respective god.

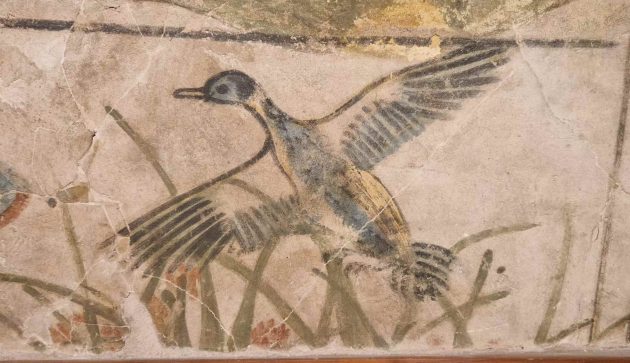

Ibises were considered sacred to Thoth, the god of wisdom. More than 4 million ibis mummies were found in the catacombs of Tuna el-Gebel, and another 1.75 million in the burial ground of Saqqara (source). For this specific species, the genetic diversity of these birds suggests that they were not purpose-bred in a hatchery but rather attracted to a lake or wetland and then caught.

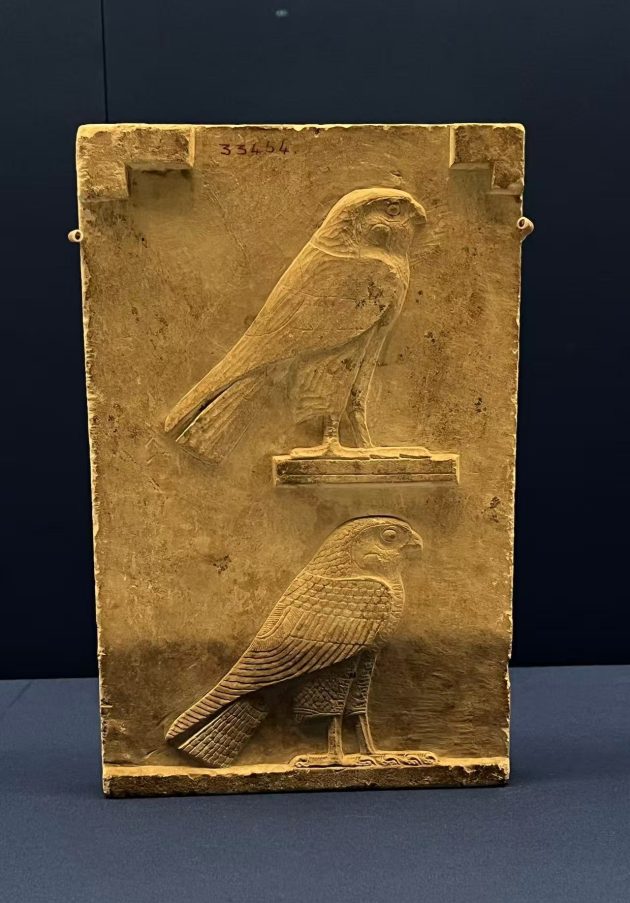

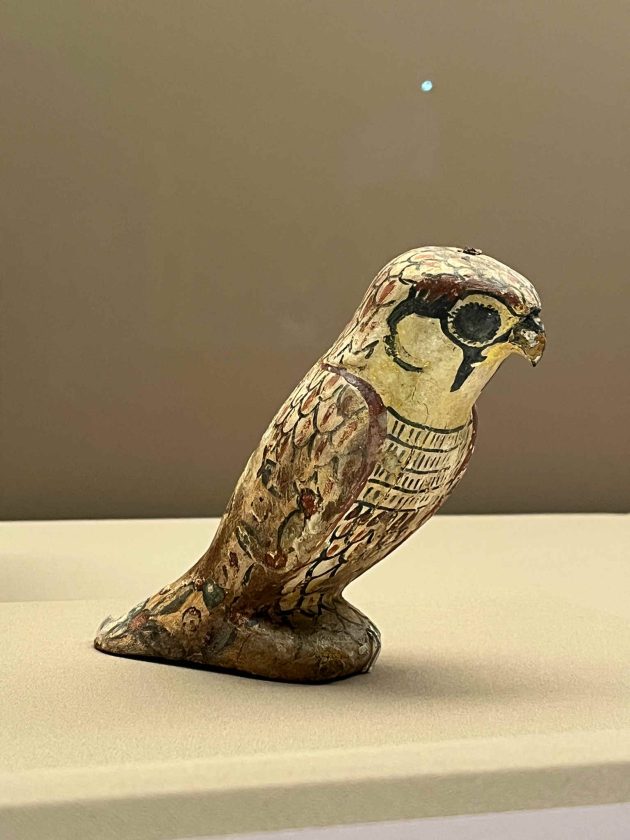

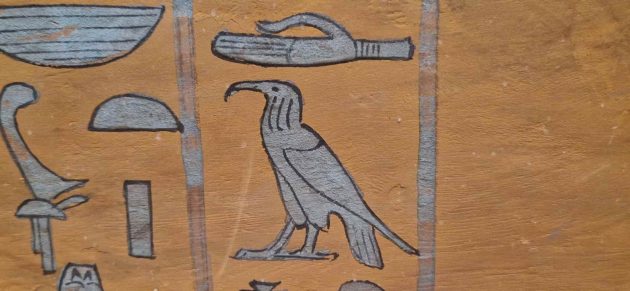

Falcons were sacred to Horus, the falcon-headed god of kingship. Falcon eggs may even have been artificially incubated in ovens, and the hatchlings raised by hand (source).

Apparently, the box under the statue shown below contains the innards of the bird.

There was also Nekhbet, a winged vulture-headed goddess, who was the protector of pharaohs and queens as well as several other groups of people.

A more obscure god, Geb, was believed to be the deity of the earth, and because the hieroglyph for the name Geb was a goose, the god was often shown with the head of a goose.

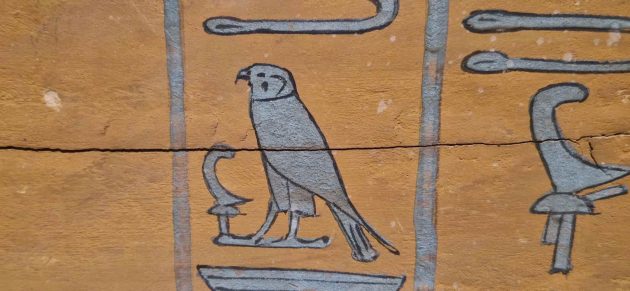

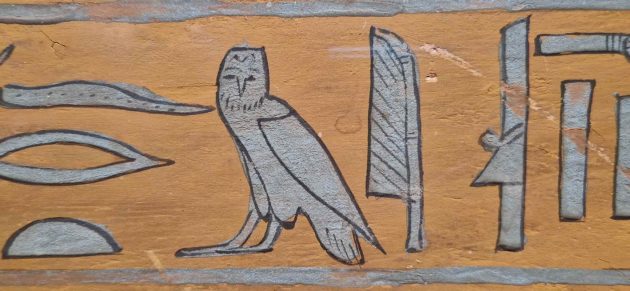

Birds also featured in other hieroglyphs, as shown below.

And there are even some ancient bird traps that survived the last 2000 years, such as this one – though I have no clue how it may have worked.

All photos taken at the exhibition “On Top of the Pyramid: The Civilization of Ancient Egypt” in the Shanghai Museum. Most exhibits are from the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

A completely different world and worldview. Fascinating.

Very fascinating! Thanks for this insightful post!

Thanks, Hendrik! My other love are cats – and unfortunately, the Egyptians mummified those, too. Should have stuck with humans.