When I first read the title “The Arrogant Ape — The Myth of Human Exceptionalism and Why It Matters”, I knew I had to read it. Why? I’ve always suspected that humans glorify their own species, just as individuals tend to glorify themselves. In my work as a management consultant, I’ve never heard a client say their problems were simple — everyone insists their work is more complex, their challenges more daunting than anyone else’s. It’s the same logic as driving ability or Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon: “Every child is above average.” If this is true at the individual level, why wouldn’t it apply at the species level too?

Christine Webb, the author of the book, puts it more sharply in the first chapter: “Psychologists have shown that people overemphasize their own abilities and accomplishments to conceal actual feelings of shortcomings and failure. When it comes to other species, do we have a so-called superiority complex?”

She goes on to argue that this superiority complex — human exceptionalism, or anthropocentrism — lies at the root of the ecological crisis. It grants us a sense of dominion over nature, the entitlement to commodify other species, and it is backfiring badly: forest fires, sea-level rise, mass extinctions, even pandemics.

And Webb quickly dismisses the claim that humans are exceptional simply because we have distinctive traits: “All species have evolved specialized adaptations to their environments. If humans are unique, then every species is unique. However, human exceptionalism is different from human uniqueness. Human exceptionalism suggests that what is distinctive about humans is more worthy and advanced than the distinguishing features of other forms of life.”

With sharp arguments, cultural references (even The Onion), and personal stories, The Arrogant Ape makes a strong case. Fortunately, Christine agreed to talk with 10,000 Birds about her book and its implications.

What first prompted you to write The Arrogant Ape? Was there a single event, or was it a series of observations? You include personal scenes in the book — caged chickens, dissected frogs — that seem formative.

I grew up loving other animals, and was captivated by evolution when I first learned about it in school. But I also took part in frog dissections and learned about industrial farming…experiences that felt deeply contradictory. If we’re all animals, all branches of the same tree of life, why treat them as objects?

Becoming a primatologist only sharpened those questions. Studying other species up close revealed remarkable continuity across the animal world, yet I still saw how entrenched anthropocentric biases are, even in fields devoted to studying other species. I began to see how deeply human exceptionalism permeates our culture, science, and imagination.

Years later, when I taught a Harvard seminar called The Arrogant Ape, I watched students’ worldviews change as they unlearned human exceptionalism. Mine did too. Those transformations are what ultimately inspired me to write this book.

Much of the book mixes personal narrative with scientific discussion. Some scientists avoid autobiographical material. Did you worry that including these personal stories might affect how the scientific community perceives the work?

One challenge in science today is the lingering belief that our personal stories and values don’t influence our work. But they do! And I believe that being transparent about that can strengthen (not compromise) scientific credibility. This isn’t the dominant approach in the field, and some scientists will certainly disagree. But storytelling is also part of what makes these ideas accessible and engaging for a broader public, and that’s ultimately who I wrote the book for.

Early in the book, you describe an encounter with a baboon named Bear — a moment you describe as evidence that nonhuman primates can “read” human minds. That passage feels intuitive; however, scientists might frown on the importance of personal observations compared to controlled experimental data. Does this concern you?

I think we need both. My interpretation of Bear’s behavior as “theory of mind” (the capacity to know what another knows) draws on two things: decades of research showing that baboons and many other animals possess related abilities like empathy, and the specific details of that moment with him. Taken together, the most parsimonious explanation is that he understood something about what I was thinking.

We’re often taught that the “simplest” explanation in science is the non-cognitive one. But sometimes it’s simpler to assume evolutionary continuity—that closely related species share similar mental capacities. From that perspective, recognizing a theory of mind in Bear is not a stretch.

More generally, much of your critique rests on cultural and linguistic patterns (how science writes about animals, classroom rituals like frog dissection, etc.). How do you gather and evaluate that kind of evidence?

The dissection “rite of passage” I describe comes from ethnographic work by sociologists, and the linguistic examples (e.g., euphemisms like “sacrificing” and “euthanizing” research animals) are based in part on empirical research in psychology. Fields like STS and the history/philosophy of science are dedicated to examining how scientific practices and norms develop, and I find their insights invaluable for understanding the broader context in which science operates.

You suggest human exceptionalism is strongest in Western culture. Have you found significant cross-cultural differences in your research? As a Westerner living in China, I find it hard to see a lower belief in human exceptionalism here compared to Germany — if anything, it seems stronger.

Many of the ideas that shaped modern notions of human exceptionalism emerged from Western philosophical and religious traditions, which later suffused Western science. Western science is the tradition I was trained in, so it’s the context I know best. That doesn’t mean other cultures don’t have strong versions of human exceptionalism too, but the book concentrates on the lineage most directly tied to the science I’m writing about.

Do you get pushback from religious communities — for example, from Christians who interpret the Bible as granting humans a special, God-given status?

Sometimes, yes. But as I clarify in the book, there are also far less anthropocentric readings of the Bible. Human exceptionalism is certainly a dominant interpretation of this text, but Christianity (like any religion) is not a monolith. Many Christian thinkers and communities emphasize humility, stewardship, and kinship with other forms of life.

You teach a course on The Arrogant Ape and describe students changing their minds over a semester. What changes, and is it lasting?

Students start to notice how deeply human exceptionalism shows up in everyday life – in our economics, food systems, education, law, politics, language, and science. They see how often we “stack the deck” against other species by studying them in captive settings or by measuring their abilities through human-centric standards.

As that awareness grows, the world often feels more alive to them—full of sentience, diversity, and complexity. Many describe feeling a renewed sense of connection, awe, humility, and curiosity about nature. Some go on to work in environmental or animal advocacy, so for at least a portion of them, the shift seems to be lasting.

Your book argues that anthropocentrism causes large-scale ecological problems. That suggests change is needed. What practical, realistic steps do you think organizations could take to weaken human exceptionalism? And at the individual level, what matters most beyond the usual ‘recycling’ list?

At an organizational level, weakening human exceptionalism begins with acknowledging how deeply it’s built into our systems – in our laws and politics (where only humans count as “persons” with rights), our economics (where forests gain value only when cut down), our food systems (which treat trillions of animals as commodities), and even our education (where students often learn about nature by dissecting or uprooting it). Anthropocentric assumptions also make their way into AI systems, since large language models are trained on human-generated data.

Practical steps include redesigning policies with ecosystems and multispecies justice in mind; valuing living beings while they’re alive; and reorienting education around ecological literacy. At the individual level, the most meaningful changes go beyond recycling — they’re about attention and relationship: learning the species we share space with, making food choices that reflect care, rethinking our language (e.g., terms like “natural resources” or “seafood” frame nature instrumentally, while calling other beings “it” distances us even further), and regularly asking what story about our place in nature our choices reinforce.

Your website mentions translations into many languages. Did you expect the book to strike such an international chord?

I knew these ideas were striking a chord in the U.S., which is part of what motivated me to write it! But I am thrilled by the international reception too.

You write about how language in science can reduce animals to objects. Is this particularly intense in fields like lab sciences (personally, I encountered it in chemical papers, in which the lab mice are mentioned in the “Materials and Methods” section), or do you see it across disciplines?

Great question. I do think it’s more pronounced in fields where harmful methods are common – the objectified language serves to rationalize or sanitize that harm. But it’s certainly not limited to laboratory science. Even in conservation science (which is ostensibly about helping/protecting other species), there can be a strong focus on populations and biodiversity metrics rather than on the lived social, emotional, and cultural experiences of individual animals. But this is an empirical question, and you (or someone) should conduct a study on how objectifying language appears across different branches of animal science!

You often cite internet ephemera (for example, The Onion) and lesser-known sites. How do you find these cultural artifacts? Do you spend a lot of time searching online, or do you follow set feeds, alerts, or networks that surface striking examples?

I worked on this book for years, and throughout that time I flagged anything that struck me – news/headlines I came across, relevant essays, or pieces friends and colleagues sent my way.

If you could enact one single change tomorrow to weaken human exceptionalism, what would it be?

I would probably transform our food systems, which not only cause unthinkable animal suffering. They’re also among the most ecologically devastating and the most intimately tied to our daily lives. Shifting how we produce, choose, and honor the food and land we depend on could ripple outward into so many other facets of our society.

How optimistic are you that societies will meaningfully shift away from anthropocentrism within the next generation?

I’m neither an optimist nor a pessimist when it comes to this stuff. As I write in the book, I tend toward hope, which is different from optimism or pessimism because it isn’t about probabilities; it’s about acknowledging uncertainty. I do not know when we’ll move away from anthropocentrism. What I do know is that Nature is imposing limits on our hubris: global warming, wildfires, rising seas, pandemics like COVID-19. As one reader recently wrote to me, “Ultimately, the cosmos will teach us otherwise.” I agree – and in many ways, it already is.

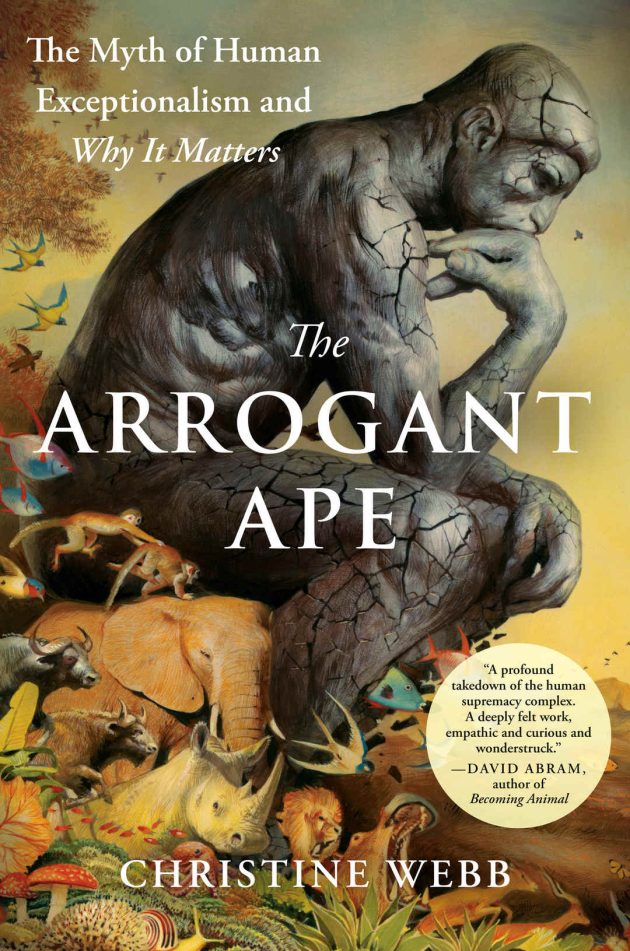

The Arrogant Ape: The Myth of Human Exceptionalism and Why It Matters

Author: Christine Webb

Publisher: Avery

Publication date: September 2, 2025

ISBN: 978-0593543139

Thanks Kai, great interview and a better understanding of a feeling I have always had, especially during my scuba photography days and now bird photography! Nature and evolution is truly wondrous and boy is mankind really making a mess of it all!

Thanks Brian – and also again to Christine who did not hesitate when I asked her for an interview

Really enjoyed this! I was reminded of some of Aldo Leopold’s work on reframing the position/importance of humans in a larger ecological framework. I shall have to add this book on my list.