Whiskey Month at Birds and Booze:

This January, Birds and Booze at 10,000 Birds is setting its sights on whiskeys all month long. The cold and dreary dead of winter is as good a reason as any to warm up with a restorative dram of uisce, especially after a blustery morning spent scanning flocks of gulls on an icy shore, trudging through woodland snowdrifts in search of new year-birds, or any other half-crazed birding one does in January. But seeing as the month is also bookended by Hogmanay and Burns Night, we’ll gladly take the opportunity to visit– in spirits, at least – the rugged Celtic landscapes of Scotland and Ireland where whiskey was born and – with luck – have a look at the birds that inhabit them.

For a land that can lay claim to an abundance of such wonderful native wildlife, it’s peculiar that the national symbolism of Scotland is so populated by mythological creatures. For starters, the official national animal is the unicorn, a fairy-tale beast chosen by Scottish royalty in the Middle Ages for its reputation as the natural enemy of the lion, the adopted mascot of English kings. Undoubtedly, medieval Scots also admired the unicorn for its willingness to die rather than submit to captivity, a fierce resolve that resonated with their own struggles against English conquest.

Scottish iconography: The unicorn, the thistle, and the arms of James V carved in stone on the gatehouse of the Palace of Holyroodhouse in Edinburgh.

Next up in the symbolic menagerie of Scotland is the blue-tongued red lion rearing up on its hind paws (or a lion rampant, for you vexillogists out there) that graces the royal arms and standard. A somewhat more credible selection to be sure, as lions actually do exist, but one that sadly snubs the native Scottish wildcat in favor of a felid that’s been extinct in Europe since antiquity. And then there’s that most infamous reputed resident of Alba, that original cryptid: the possibly prehistoric, possibly piscine, possibly reptilian, but undoubtedly make-believe Loch Ness Monster.

****MEGA

Luckily, we needn’t wander into such whimsical territory to find Scotland’s putative national bird. While it has no official status – at least not yet – many Scots regard the Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) as their national avian mascot. Even though a 2013 petition by the Royal Society of Protection of Birds failed to convince the Scottish parliament to make it official, the campaign to make the Golden Eagle Scotland’s national bird continues. And while birders might instead make the case for an endemic like the Scottish Crossbill (Loxia scotica) or a tough, native gamebird like the Capercaillie (Tetrao urogallus), the Golden Eagle has a lot going for it. Granted, it may lack the fairy-tale cachet of a unicorn, or a lion Europe, or some antediluvian relict lurking in the depths of a Highland loch, but the Golden Eagle is unquestionably one of the most majestic and imposing of Scotland’s extant fauna.

Pair of Golden Eagles (1899) by Scottish painter Archibald Thornburn (1860-1935).

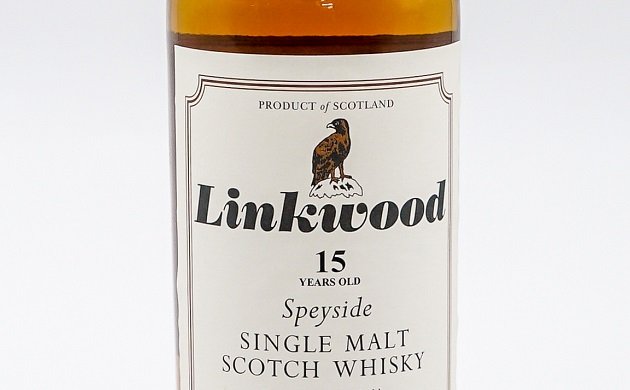

Whisky makers in Scotland also appear to prefer reality over fantasy in choosing animals to adorn their labels and bottles, and the Golden Eagle has always been a popular choice. A silhouetted Golden Eagle in flight appears on all current bottlings by Ardmore, and over the years, the same species has occasionally appeared on various products by Scottish distilleries like Glenfarclas and Mortlach. There’s also one on the otherwise rather plain label of this week’s feature: a bottling by whisky merchants Gordon & McPhail of a 15-year old Speyside whisky by the Linkwood Distillery in Elgin, from northeastern Scotland’s famous Strathspey region.

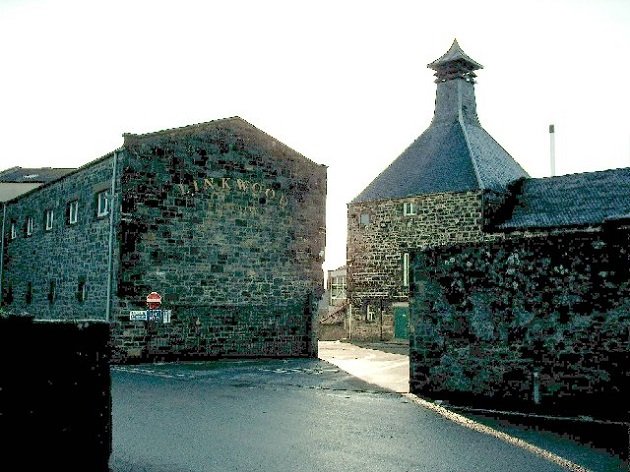

Linkwood was founded in 1821 alongside the scenic Linkwood Burn, from the distillery takes both its name and its cooling water from a stream found a little way southeast of the town center. Swans swim on a small pond on the distillery grounds and deer and otters can be found by a trail that runs beside the burn. Most of Linkwood’s production is sold to blenders, and it’s in especially high demand as a “top dressing” for labels like Johnnie Walker and White Horse. Occasionally, though, the distillery’s casks are aged and bottled by other firms, as in this 15-year-old expression sold by Gordon & McPhail, an outfit also located in Elgin that was for many years the only officially licensed bottler of Linkwood.

The traditional pagoda roof of the Linkwood Distillery, an architectural innovation introduced in the late nineteenth century that offers improved air circulation to the fires of the malt kiln.

The Speyside is Scotland’s most productive distilling region and its whiskies are often glibly characterized as soft, sweet, and refined, contrasting with the hard-edged smokiness of Islay single malts or the more rugged flavors found in the rest of the Highlands. Of course, not all Scottish whiskies fit neatly into these regional generalizations, but Linkwood distills a product in keeping with the classic assessment of Speyside whiskies. In the hands of Gordon & McPhail, Linkwood 15 enjoys a generous barrel-aging that manifests itself in an intricate, aromatic nose, rich in sherry and oak but also sweet with touches of honey and ripe fruit. Bright, floral traces of strawberry, bubblegum, powdered sugar, and citrus float over a rich, warming foundation of buttery toffee, nutmeg, and woody cinnamon. The palate is creamy and smooth with brown sugar, golden raisins, and almond paste, accented throughout with anise. Linkwood 15 closes with a long, lightly spicy finish, dry but with a sweet hint of dried apricots. According to reports, Linkwood 15 has been discontinued recently – for now – but one can still find bottles on shelves, so it’s one worth keeping an eye out for.

***

While it’s heartening to witness such reverence for the Golden Eagle from distillers and bottlers of single malt whiskies, regrettably, the bird isn’t always treated well by some people in Scotland. The eagle’s alleged appetite for livestock has made it the traditional enemy of farmers and shepherds – especially in Scotland’s sheep country – and though claims of its gluttony are undoubtedly exaggerated, pardon for the Golden Eagle has been slow in coming.

Eagle and Lamb by John James Audubon (1785-1851).

But these days, the ugliest and most distressing threat to the Golden Eagle in Scotland is from the firearms and steel traps of ghillies, the gamekeepers-for-hire who wait on wealthy hunters during Scotland’s traditional upland grouse season. In addition to performing the day-to-day chores of the hunt, the latter-day ghillie is charged with protecting and increasing the grouse population on these estates, ensuring that there are enough gamebirds to flush ahead of the shotguns of high-paying clients on lucrative driven shoots. The so-called “management” of Scotland’s grouse moors and heaths for these hunts entails not only environmentally-destructive wholesale burns of heather and the draining of wetlands to supply new grouse habitat, but the merciless persecution of the grouse’s natural predators – most notably killing Scotland’s birds of prey by shooting, trapping, or poisoning. This abhorrent treatment is by no means a new practice, either, as evidenced by a troubling nineteenth-century painting by Edward Landseer that depicts a ghillie in Highland dress clutching a dead Golden Eagle.

The Highlander (1850) by English painter and sculptor Sir Edwin Landseer (1803-1873), commissioned by Queen Victoria.

Landseer asked the Queen if she wished him “to illustrate the peaceful and sunny side of the Highlanders – character in preference to Mist and savage treatment”. Her reply was that “Highland Lassie [the dog] should be all peace and sunshine – on the other hand the Highlander … should represent the national sport of the country but perhaps without actual storm.”

Occasional stories in the British press remind us that such disgraceful violence against Scottish raptors, while perhaps no longer celebrated so triumphantly on canvas, has not yet been consigned to the annals of history. But there’s new hope for Scotland’s Golden Eagles as these atrocious acts are brought to the public attention and their perpetrators prosecuted. And there’s good news, too: the Scottish government is currently considering mandatory licensing for grouse hunting estates and the South of Scotland Golden Eagle Project is working hard to increase the population of Golden Eagles outside of the Highlands.

A Golden Eagle (1916), another painting by Archibald Thornburn.

Good birding and as always, happy – but also mindful and hopeful – drinking.

Linkwood Distillery: 15 Years Old Speyside Single Malt Whisky

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Five out of five feathers (Outstanding)

Leave a Comment