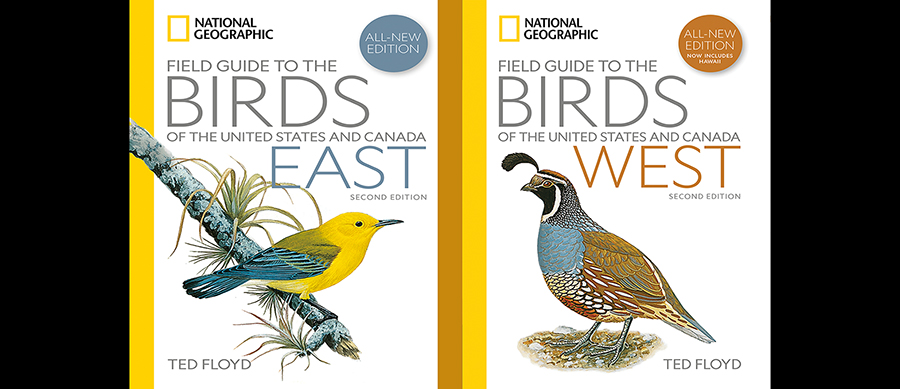

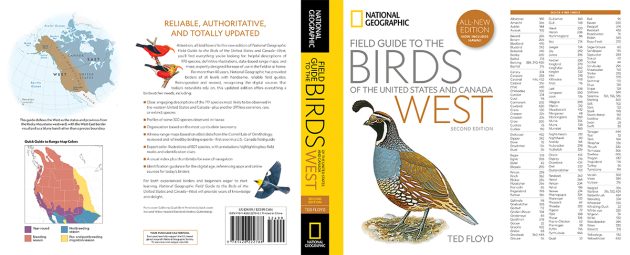

There’s a Prothonotary Warbler on the cover of the National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition, which is a little unfair since I cannot resist Prothonotaries. (Surprisingly, Prothonotaries are on the cover of only one other field guide in my collection, a small book about the Warblers of Ontario.) The California Quail on the cover of the National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition is an equally charismatic bird, but not one that makes my heart go pit-a-pat. I am happy that they didn’t use Mountain Quail, my nemesis bird, that would make my heart go dum-dum-dum. These two volumes, and the just published Field Guide to the Birds of the United States and Canada, 8th edition, all written and developed by Ted Floyd, are the latest additions to the National Geographic field guide and bird book family.

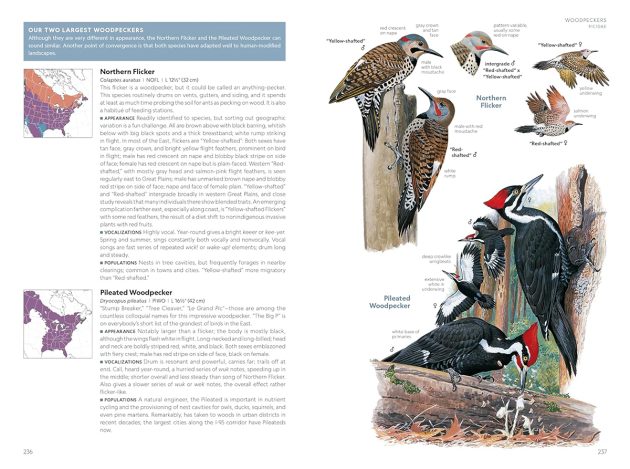

“Our Two Largest Woodpeckers” from National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition, pp. 236-237. ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

National Geographic field guides have gone through quite a few changes since the first North American Field Guide to the Birds of North America, edited by Shirley L. Scott, was published in 1984. That volume was sold as a set with bird sound records and a photographic coffee table book, though apparently you could purchase the field guide separately. Thirteen artists contributed illustrations; the text was unattributed, leading one reviewer to comment that it was apparently compiled by committee, an anonymous authorship that continued though four editions.* The fifth edition (2006) gave front page credit to Jon L. Dunn, who had been involved from the beginning, and Jonathan Alderfer, who joined the team in the 1990’s for the third edition, as had map consultant Paul Lehman.** In 2008, Nat Geo published the first regional guides to “western” and “eastern” North America, and the seventh edition of the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America was published in 2017, all volumes edited by Dunn and Alderfer. This was fairly miraculous since two years earlier National Geographic had spun its magazine, book, map, and media divisions off into a for-profit company called National Geographic Partners, with 21st Century Fox as majority owner, laying off 9% of its staff, including workers in the books division***. Since then, book publishing under the NatGeo imprint has focused on books and multimedia for children, especially after the Walt Disney Company bought Fox’s media assets in 2019.

Against this framework, it’s wonderful to see that National Geographic has started publishing books about birds again. The third edition of Jonathan Alderfer’s National Geographic Complete Birds of North America was published in 2021, Noah Strycker’s National Geographic Birding Basics came out in 2022 and now we have new editions of the North American field guides, aptly renamed to better reflect their geographic coverage. New editor/writer Ted Floyd started this project around 2021 (based on his comments in the Acknowledgments) and, while maintaining many of the excellent features of the previous volumes, particularly it’s usability tools, has introduced new, young artists, new maps, taxonomic updates, and added coverage of the birds of Hawaii. I will be reviewing the two regional guides here, and looking at the larger guide, the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of the United States and Canada, 8th edition in a future post (just received, thank you Ted Floyd and NatGeo).

As noted above, the books’ titles have been tweaked: National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of Eastern North America is now National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition and National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of Western North America is now National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition. The change from ‘North America’ to ‘United States and Canada’ is most welcome, despite the lengthiness of the title (WordPress does not like it as the title of this post!). I get tired of pointing out that geographically North America includes Mexico, and most of the Caribbean and Central America. The change was partly necessitated, I imagine, by the inclusion of Hawaii in the western volume. Hawaii’s birds were added to the official ABA checklist in 2017, based on a membership vote in 2016, and since then have become of much more interest to many U.S. and Canadian birders. Using political boundaries for a field guide, however, brings up as many questions as using the term ‘North America.’ Mainly, the United States politically encompasses 50 states, the District of Columbia (all covered in these guides) and Puerto Rico, include Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands (not included in the guide). Is it nitpicking to point this out? Definitely. Field guide authors walk a very fine line when it comes to defining coverage, amongst many other fine lines. By aligning the new NatGeo guides with the geographic coverage of the ABA Checklist, Floyd has increased the usefulness of the books to many birders.

COVERAGE

Table of Contents from National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition, pp. 4-5; ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

Table of Contents from National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition, pp. 4-5; ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

Emphasis is on coverage of birds likely to be seen in the region, resident and migratory, and on widespread birds (as opposed to species found in one small area). National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition (shortened in the future to NatGeo East) covers 586 species; 498 receive full descriptions and 88 receive brief descriptions. The latter includes rare birds like Pink-footed Goose that show up annually on the mid-Atlantic and Northeast coast, and range-restricted birds like Hook-billed Kite, found only in the lower Rio Grande of south Texas. In the Appendices, 271 additional birds are listed: 70 “Species of Casual and Peripheral Occurrence in the East” (illustrated, brief description) and 171 “Species of Accidental Occurrence in the East” (no illustrations, brief comment on records of occurrence, this section includes ‘megas’ like Steller’s Sea-Eagle). Finally, nine “Extinct and Likely Extinct Birds in the East” are described and mourned, including Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition (shortened in the future to NatGeo West) covers 717 species, with 595 of the more widespread and common species receiving full descriptions, 122 receiving brief descriptions. Appendices list 106 “Rare Birds in the West” and 148 “Species of Accidental Occurrence in the West.” The appendix on “Extinct and Likely Extinct Birds in the West” lists 37 species, including 31 Hawaiian birds (Hawaiian Crow is included since it does not occur in the wild). Unlike the individual write-ups in NatGeo East, Floyd here writes a succinct essay on human-caused extinction. As he says in the east volume, even though we cannot observe these species, knowing that they existed adds to our knowledge framework and underlines the need for conservation.

Which birds belong in the East and which birds belong in the West? This dividing line is always fuzzy, and Floyd discusses it in both introductions, noting how this is not a black and white division, and the complex biodiversity of the western region. A map showing the east-west division is handily available on the inside back cover of both guides, showing the Rocky Mountains as the dividing line (a traditional demarcation), with the note that “the East-West border [is] visualized as a blurry band rather than a precise boundary.”

SPECIES ACCOUNTS

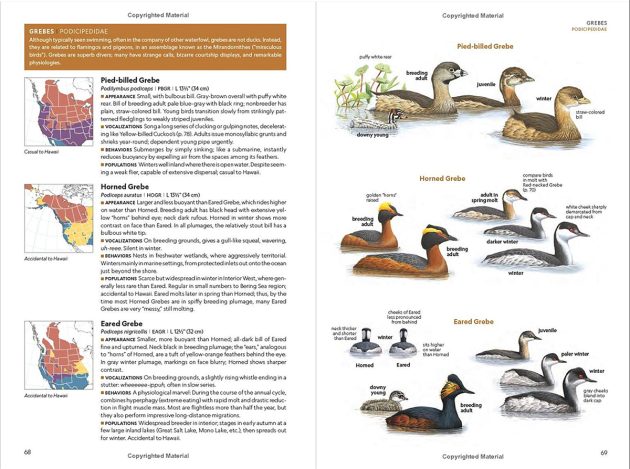

Grebes, from National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition, pp. 68-69; ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

Grebes, from National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition, pp. 68-69; ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

Species Accounts are arranged taxonomically, based to the American Ornithological Society (AOS) Checklist, as of July 2023. This means that 2024 changes–including the split of Brown Booby into Brown Booby and Cocos Booby, the split of Cory’s Shearwater into Cory’s and Scopoli’s Shearwaters, and the lump of Common and Hoary Redpolls–and the two-month-old 2025 changes are not included, though species descriptions note subspecies that were elevated to species status and the fact that Hoary Redpoll is sometimes considered a subspecies. The time lag between taxonomic cutoff and field guide publication has always been an issue for print field guides, becoming particularly notable in recent years as ornithological research and efforts to align taxonomy across classification systems result in multiple changes. One of the many arguments one could make for a revival of National Geographic’s field guide app.

Interestingly, Hawaiian species are included in the main species accounts section, as opposed to the separate back-of-the-book section in the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Western North America, fifth edition (HMH, 2020). I don’t have strong feelings about this incorporation. One the plus side, it brings Hawaii totally into the fold, so it’s no longer an ABA outsider, on the minus side, it might mislead casual readers into thinking they might encounter a Red-crested Cardinal on the mainland, on the plus side, the taxonomic placement of Red-crested Cardinal six pages away from Northern Cardinal teaches us that these birds are not closely related!

As is modern field guide tradition, text is on the left and illustrations are on the right, generally three or four species per page. There are some differences in the way each guide organizes these pages. In NatGeo East, each text page is headed with a couple of sentences about the genus or bird group described below, a helpful and fun identification aid. Floyd compares species, pointing out shared or differing features or migration routes, and sometimes just delighting in their behavior (Barn, Cliff, and Cave Swallows are “…elegant, with their bright and warm color schemes, but they also like to play in the mud…” p. 292, East). Many text pages in NatGeo East also offer boxed-off mini essays on topics related to identification of the species described on that page, birding in general, or the guide itself; examples are Situational Ethics (on the Rail page), Plumage Variation in Buteos, Parrots and Parakeets in the East (population status and which species are included in the guide), Identifying Empids Out of Range. NatGeo West sticks to the organization used by the first edition, brief summaries of the characteristics of bird families, with original text. There are no mini essays, which is understandable since there are so many more species to cover in the west. Still, I would have like to have seen the one of Situational Ethics transferred over in some way, maybe in the Introduction.

Each full species description includes Common name (in large, bold print), scientific name, banding code, measurements (in inches and centimeters), a CR or EN symbol for species considered critically endangered or endangered, a range map, and sections on Appearance, Vocalizations, Behaviors, and Populations. NatGeo East descriptions also include an overall description of the bird, often a chatty comment on its appearance, behavior, vocalization, habitat, or interaction with humans. For Worm-eating Warbler, for example, Floyd writes, “They don’t eat worms, they don’t warble, and their scientific name is misspelled (it should be Helmintheros). But Worm-eating Warblers are enchanting and much sought by birders” (p. 376, East). I really enjoyed these and wish they could have been included in the western book.

The text overall is excellent–reflecting Ted Floyd’s roots as a birder and a bird writer. It is highly readable, uses as few scientific terms as possible without losing meaning, and is often fun to read. The weakest parts are the descriptions of the Hawaiian birds, I think because Floyd has not had as much experience with them as the mainland species. Each volume is different, even with species that are common in both regions. In other words, cookie cutters were not used. The text is also meticulously cross-referenced, meaning that if a species is compared to another species, the page number of that bird’s description is given. This is a level of detail I seldom see in field guides.

The Appearance section focuses on physical features (size, shape, color), significant field marks, and how to distinguish the bird from other species. For example, Horned Grebe is described as “Larger and less buoyant than Eared Grebe, which rides higher on water than Horned” (p. 68, see above illustration). Vocalizations offer descriptions of calls, songs, and nonvocal sounds when relevant to identification. Transcriptions of sounds are often included, and sometimes, as with the above grebes, info tidbits on when and where you are likely to hear them. The Populations section has a wider scope than one would expect, combining information on range, habitat, and additional factors in population growth, and decline–migratory patterns, breeding sites, possible hybridization, status of food source, and sometimes miscellanea, such as the note in Purple Swamphen that the eBird name is Grayheaded Swamphen.

Range Maps are very different from those of most field guides. Sourced from eBird, as part of a partnership between National Geographic and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the maps show life cycles rather than the typical seasonal distribution. Four colors represent the cycles: purple for year-round residence, a dull red for breeding, yellow for migration, and a dull blue for nonbreeding. Floyd goes into detail about the construction and meaning of these maps in the Introduction, emphasizing the fluctuating diversity of birds’ life cycles and movements–sea birds are in their nonbreeding cycle when present in the northern hemisphere in summer, not all birds here during their breeding cycle are breeding, birds may engage in long stopovers during their migratory cycle. I would have appreciated a little more guidance on how to reset my brain to use them effectively, it really is a big leap in process for field guide users. And exception to this new concept are the range maps for the Hawaiian Islands (in the western volume) are uncolored outlines of the islands with notes below indicating on which island(s) the species can be found. Additional information is found in the Populations section.

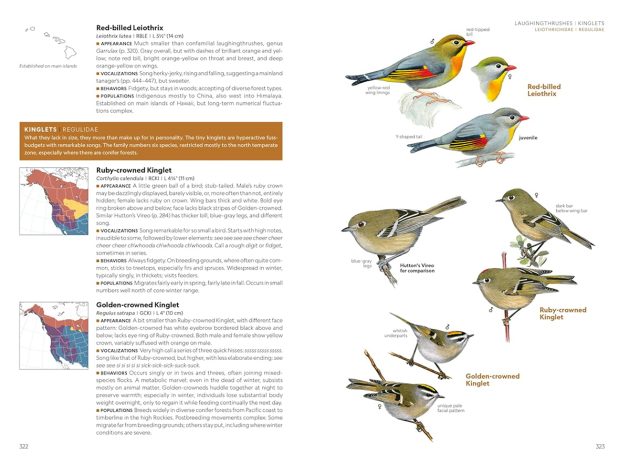

The Red-billed Leiothrix is one of the Hawaiian birds drawn by artist Andrew Guttenberg in National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition, p. 322; ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

The Red-billed Leiothrix is one of the Hawaiian birds drawn by artist Andrew Guttenberg in National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition, p. 322; ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

The illustrations on the right side of the species accounts complement and supplement the text, showing the species in profile and often in flight, illustrating the diversity of plumages apt to be seen in eastern or western United States and Canada: juvenile, 1st summer, 2nd summer, winter, 1st winter, breeding adult, nonbreeding adult, subspecies by name or geographic area. The overall look is bright, clean, easy to read and study, in many cases less cluttered than previous volumes. This is due to several changes: a decrease in descriptive text notations (many of these are already on the text page); less birds crowding each page; the use of space and headings to separate bird groups, and an overall sense of graphic design that understands how the eye travels when looking at these art-filled pages. Andrew Guttenberg is responsible for “layout arrangement [and] annotation composition” and Marquette (Marky) Mutchler “helped compose the art annotations, paying particular attention to the technical aspects of avian anatomy” (p. 436, Acknowledgments). The cleaner design helps us appreciate the beauty of the hundreds (thousands?) of bird illustrations in these volumes.

The artwork itself is by the many artists who contributed to the National Geographic series over the years, and they are listed in the Illustrations Credits, first in a group, and then per illustration (in very small print with no breaks). Notable contributors are Jonathan Alderfer, H. Douglas Pratt, Peter Burke, David Beadle, John Janosik, Michael O’Brien, Mark R. Hanson, Cynthia J. House, Killian Mullarney, John P. O’Neill, Diane Pierce, John C. Pitcher, Thomas R. Schultz, and John Schmitt. Young birder artist/ornithologists Andrew Guttenberg and Marky Mutchler contributed new illustrations: enhancements to longstanding species, like Guttenberg’s American and Sprague’s Pipits in flight (east volume); new species, like Mutchler’s exquisite drawings of Juan Fernandez, White-necked, Bonin and Black-winged Petrels (west volume); and the new Hawaiian birds, beautifully drawn by Guttenberg. Hopefully, future volumes will be able to use more of their talents.

This spread of the back and front covers of NatGeo West shows the map reference keys and the Quick-Find Index. National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition; ©2025, National Geographic Partners, LLC

The field guides retain the features that made previous volumes, regional and North American, so easy to use in the field and at home: thumb tabs (still six, though in different order); a Quick-Find Index on the inside front cover flap; a Visual Index of Bird Families on the inside front and back covers; maps on the inside back cover flap showing East-West divisions and a Quick Guide to Range Map Colors; Table of Contents in the front of the book (including page numbers for each family–it’s amazing how many guides don’t do this); and an index in the back of the book. I was particularly happy to see the thumb tabs again, I find them comforting, like they’re saying, “Don’t be overwhelmed by all these pages, here’s a way in.” Comparing the Visual Index pages of the first and second editions is an interesting exercise in scanning taxonomic and range changes over the past 16 years, so many species in different places on the grid, some species gone (Northern Jacana has been sent to the Rare Birds Appendix), some species new (Pin-tailed Whydah in NatGeo West, a species not even included in the first edition). I like that the indexes include topics as well as species names (common and scientific); this is especially useful when using NatGeo East, with its topical mini essays. One misstep to note for future editions–Brown Booby is not listed in the NatGeo East index under “Booby,” though it is described with the other Boobies on page 180 and it is listed under its scientific name and in the western edition. The five-page Glossary offers definitions of anatomical features, organizations, and taxonomic terms used throughout the books.

The guides are roughly the same size and weight as the previous editions, which means they will fit into a backpack but probably not a pocket. The flexbound covers are fairly sturdy and the binding looks like it will stand the test of being opened wide dozens of times to the same pages on sparrows and shorebirds. I did have a problem with the print. Most of the text, aside from headings utilizes a very light sans serif font; it appears to be printed in a gray color, but this may just be because the lines that make up the letters are so thin. This makes the guide difficult to read unless you’re using a strong light. At the moment, I’m reading it under an LED reading lamp from IKEA and it looks fine. Reading in my car on a cloudy day is more challenging, though after a few minutes I found that my eyes adjusted. This is not a problem with just these guides. Lately, I feel like every other new field guide has print that is too thin or too small or too light and while it would be convenient to chalk it up to my older eyes, I hear comments from other, younger birders. Please, publishers, do what you need to do to give us more accessible print! And test readability with people of all ages and backgrounds!

BIO & CONCLUSION

Ted Floyd is a birder, writer, editor, educator, speaker, and friend. Widely known as the editor of the American Birding Magazine’s Birding magazine, which he took on in mid-2002 and now co-edits with Frank Izaguirre, Ted has also written five books, including the Smithsonian Field Guide to the Birds of North America (HarperCollins, 2008, available from Scott & Nix), How to Know the Birds (National Geographic, 2019), and the ABA Field Guide to Birds of Colorado (Scott & Nix, 2014). He’s also written scholarly journal articles, technical papers, popular magazine articles, and book chapters, all, of course on birds, ornithology, and related topics, and is a frequent guest on the popular ABA Podcast. Floyd received a B.A. in Ecology & Evolutionary Biology from Princeton University in 1990 and a Ph.D. in Ecology from Penn State University in 1995; in 2022 he received the ABA Claudia Wilds Award for Distinguished Service.

In the National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition and National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition Floyd has taken on a daunting task, redeveloping a valued field guide series. Floyd speaks about his goals in the first sentences of the Introduction, “It has been more than 15 years since the first edition of this book was published. In that time, both the science of ornithology and the experience of birding have changed tremendously. This new edition reflects and responds to these changes.” He states that “the guiding principle behind this volume, whether you use it at home or in the field, is efficiency of presentation. Species accounts, art, and maps have been created to succinctly convey the essentials for accurate identification of all the bird species occurring regularly in the West” (or East, depending on the volume).

This is really the essence of any good field guide, and I think Floyd has largely succeeded. Coverage of species has been updated and expanded, new birds added, old birds relegated to the back of the book, taxonomic changes applied to family organization, species lumps and splits, name changes. A lot has happened in 15 years! The rewritten species descriptions are exceptional, rising far above the technical text of many field guides in their lucidity and wit, presented in a highly readable graphic format. Similarly, smart redesign of the illustration pages helps the user find and study the bird they need quickly, with little distraction. New artists have been added to the NatGeo repertoire, bringing with them new ways of drawing birds and fresh perspectives. Usability features, always excellent, have been retained. There are some changes that require adjustment and maybe some user education, mainly the eBird sourced range maps. And there is one element that I hope will be improved–legibility of print. Meanwhile, I’m looking forward to reading the third volume of this new series, Field Guide to the Birds of the United States and Canada, 8th edition.

* Hall, George A. The Wilson Bulletin 97, no. 4 (1985): 575–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4162163. Authors were acknowledged in the back of these early guides as consultants.

** Dunn talks about how he came to work on the NatGeo series in the Western Field Ornithologists Newsletter, Dec. 2020. https://westernfieldornithologists.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Dec2020-Newsletter.pdf

*** “National Geographic Lays Off Staff Ahead of Asset Sale,” Philanthropy News Digest, November 6, 2015, https://philanthropynewsdigest.org/news/national-geographic-lays-off-staff-ahead-of-asset-sale

National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada East, Second Edition by Ted Floyd

National Geographic, distributed by Penguin Random House, 448 pages; 5.45 x 0.81 x 8 inches; 9.3 ounces

ISBN-10 : 1426222777; ISBN-13 : 978-1426222771

$24.99 (discount from the usual suspects)

National Geographic Field Guide to Birds of the United States and Canada West, Second Edition by Ted Floyd

National Geographic, distributed by Penguin Random House, 496 pages; 5.46 x 0.9 x 7.99 inches; 1.43 pounds

ISBN-10 : 1426222785; ISBN-13 : 978-1426222788

$24.99 (discount from the usual suspects)

Do I need both guides if I already have the complete, coast-to-coast guide? And where lies the border between east and west?

And wouldn’t it make more sense to have one guide for true MAGA America and another one for marxist woke communist America? A true MAGA birder certainly would not want to bird in a blue state …

To Peter, I would say the border between East and West is the Mississippi River – although many Eastern birds are found west of the Mississippi and fewer Western birds are found east of the Mississippi. You don’t need a new guide if you like your coast-to-coast guide, but my guess is that it’s a large book. I think many birders probably use digital tools now (I still use books); nothing, in my view, replaces a good field guide. It has been a trend for awhile now – driven in large part by the popularity of the Sibley East and West guides – to split the country in two for more manageably-sized guides. To Kai, I would say, not sure how many MAGA birders there are, but I know that there are some. Believe me, they know where the blue states are. But I would argue that it is more likely the marxist woke communist birders who want to avoid birding the red states. Problem is, the red states have so many fabulous birds. As always, Donna’s is a stunning, covers all the bases, review. It is easy to see how the new 8th editions are gigantic upgrades. I still have not decided if I will make the investment. But for anyone newly becoming involved in birding – I would strongly consider the fully updated Nat Geo guides. The Sibley guides still need all the taxonomic updates that have occurred over the past 10-12 years. Understandably, a gigantic revision.

Actually, it’s most likely non-Marxist, non-Communist Black birders such as myself who may avoid the Red States ’cause I’d rather be alive birding watching in Connecticut, then dead trying to birdwatch in Alabama.