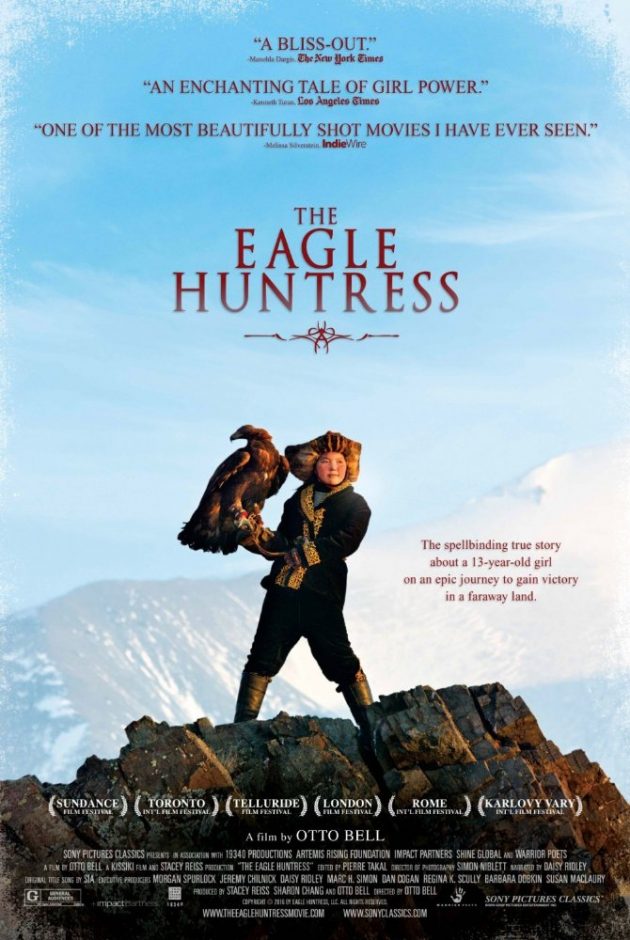

Aisholpan Nurgaiv is a graceful, rosy-cheeked 13-year old girl with a magic smile who makes living on the edge of nowhere and forever look like the easiest experience in the world. Even when hunting in sub-freezing temperatures on the edge of the Mongolian border or doing her chores around the family ger (yurt) in the isolated Altai Mountains, Aisholpan beams. She is The Eagle Huntress, the young Kazakh star of this captivating film, and her joy comes from a life integrally connected to nature.

The Eagle Huntress is a documentary about Aisholpan, her path to becoming an eagle hunter, a cultural heritage usually taken on by males, the family that supports her, and the Mongolian Kazakh community that seeks to continue the ancient tradition with its Golden Eagle Festival. Many readers have hopefully already seen this film in the theatre. It has been released in DVD, and I’ve found it just as captivating to watch in a small frame format as on the screen, though sometimes in different ways.

The Eagle Huntress is a documentary about Aisholpan, her path to becoming an eagle hunter, a cultural heritage usually taken on by males, the family that supports her, and the Mongolian Kazakh community that seeks to continue the ancient tradition with its Golden Eagle Festival. Many readers have hopefully already seen this film in the theatre. It has been released in DVD, and I’ve found it just as captivating to watch in a small frame format as on the screen, though sometimes in different ways.

The film has a simple narrative, which is part of its charm. It’s constructed in three acts: Home, Festival, Hunting. In Act 1, we meet Aisholpan and her family—her eagle hunter father, Rys, her hard working mother, Almagul, her younger sister and brother, and her grandfather, also once an eagle hunter. Eagle hunting is a family tradition that goes back at least 12 generations, part of the larger nomadic Kazakh culture. So, when Aisholpan tells her father that she too wants to work with a Golden Eagle, he is sweetly supportive, and says, “She’s not afraid of it at all. maybe it’s in her blood as well.”

Aisholpan, in traditional eagle hunter garb, first trains with her father’s eagle, and then, in the climax of the act, we witness her and her father stealing a young eagle from its nest on the side of a steep cliff. It’s a gripping scene, especially as Aisholpan struggles to capture the lively young bird on the small cliff ledge as the parent eagle flies overhead. Her confidence is amazing. “Girls can do anything boys can if they try, ” she says at one point. (And filmmaker Bell confirms in the DVD commentary that this was one of the first things Aisholpan, a shy girl, says to him.) We’ve already seen Aisholpan at boarding school in town, studying, laughing with friends, taking care of her younger sister. We know from the beginning of the film that this is a determined, smart girl who doesn’t grumble or whine. She just does it.

Photo by Asher Svidensky, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

But, let’s go back to that eagle stealing for a minute. This is probably where some birders will stop and say, “What? They’re stealing the eagle? That’s not right.” But, this isn’t our world; this is the world of the Kazakh culture where this form of falconry has cultural and historical resonance. Significantly, The Eagle Huntress begins with an older eagle hunter releasing his Golden Eagle. This is part of the tradition, to release the eagle into the wild after seven years. The opening scene speaks to the relationship of respect Kazakhs have developed with their eagles and the generational cycle that Aisholpan is about to become a part of. (I was also happy that there were two eaglets in the nest, so the parents were not bereft.)

Aisholpan’s father, Nurgaiv; photo courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

The Golden Eagle Festival in Olgii (also called Bayan-Ulgii), Mongolia, is full of color and sound. The center of attention are the eagle hunters, erect on their horses, hands protected by thick leather gloves holding their hooded eagles, arms propped up by handmade wooden rests attached to the saddle, weathered faces framed by splendid fur-trimmed hats. (If this image sounds familiar, it may be because photographs of Kazakh eagle hunters are on the cover and title page of the encyclopedic Birds & People by Mark Cocker.) The hunters look at Aisholpan curiously (in his DVD commentary, Bell says that the people in charge of the festival were told she was coming, but most of the participants did not know), you can hear laughter and a little scoffing in some scenes, and for the first time Aisholpan loses her smile. But, not for long.

The scenes where Aisholpan and her young eagle compete are filled with tension and joy. Bell uses the musical score by Jeff Peters smartly, bringing up the volume to emphasize the majesty of the hunters riding in and the suspense of Aisholpan’s eagle in flight, and lower it so it is barely underlying the sounds of the festival. These scenes also give us a sense of the larger Kazakh community. There is a courtliness in the way they treat each other, but the camera also picks up the women in the background, making the post-festival meal but not partaking of it. That’s for the hunters, including Aisholpan.

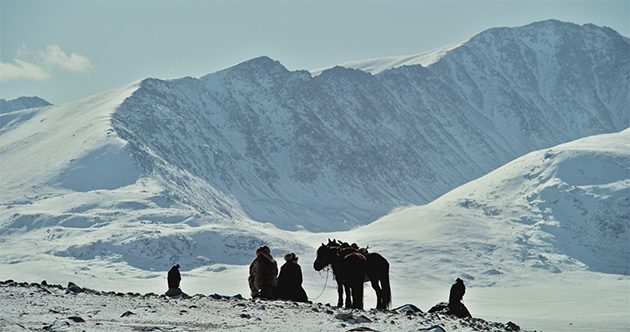

In Act 3, the scene changes from town and crowds to the vast wilderness of far western Mongolia. Aisholpan will not be considered a true Eagle Hunter till she successfully hunts. The community elders express skepticism about her ability in a scene that is both funny and sadly familiar. So, Aisholpan and her father travel to what looks like the ends of the earth—a land of nonstop snow and little else. And, it’s cold, bitter cold. We learn just how cold it is in the DVD commentary, where Bell talks about equipment breaking and the impossibility of shooting more than a few hours a day.

Hunting in western Mongolia; left to right: Aisholpan’s father, Nurgaiv and Aisholpan and their Golden Eagles. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

It’s a little disorienting to go from the conviviality of the festival to the struggles of the hunt. It takes days to find a fox for the girl and her eagle to hunt, and the first effort does not go well. And, if you’re like me, you’re a little distracted by wondering how the crew actually got the magnificent overhead scenic and parallel action shots. But then, a fox is sighted and we get truly magnificent scenes of the bird in flight and all attention is focused on the beauty of this Golden Eagle. And, when the eagle fights and ultimately kills the fox, we get a bloody glimpse into another side of eagle hunting—its savagery and its original purpose. It’s exciting. It’s part of the natural order of things. And, it’s an important step in Aisholpan’s path to becoming an Eagle Hunter—a role usually reserved for boys and men, but one that she assumes with talent, determination, and grace.

The Eagle Huntress was conceived and directed by Otto Bell, a British filmmaker currently based in New York City. The breathtaking cinematography is by Simon Niblett, with additional photography by Martina Radwan (who filmed the school scenes) and Christopher Raymond (according to the DVD commentary, photographer Asher Svidensky also filmed, though he is credited as a producer). The film is narrated by Daisy Ridley. Morgan Spurlock, the documentary filmmaker who made Super Size Me, is executive producer. (There are many producers and executive producers listed, including Ridley, but Spurlock is credited by Bell as being the prime mover for financing and moving forward when the filmmakers ran out of money.)

The story behind the film is this: Asher Svidensky, an Israeli photographer, went to western Mongolia to photograph the eagle hunting tradition and found Aisholpan. He took stunning photos of the girl, 11 years old at the time, in hunter dress—red hat bordered broadly with fur, black tunic embroidered with gold–holding her father’s Golden Eagle (you can see the photos and read his story on his web site). Svidensky’s photographs were published on the BBC website, where they were seen by Otto Bell. Bell was struck by the story in the photos—a young girl adept at an historically male tradition in a beautiful, remote setting—and decided he had to make this film.

Aisholpan and her father Nurgaiv; Photo by Asher Svidensky, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

I highly recommend watching the DVD with the director’s commentary to learn more of how The Eagle Huntress was made. The film makes everything look easy. In the commentary, Bell talks about how the filming was a learning curve on the job: With no electricity, a generator had to be brought in, powered by gas; they would run out of gas for the generator and have to siphon it from their vehicle, but not too much or else they wouldn’t be able to go home. A GoPro camera attached to Aisholpan during the eagle stealing episode produced mostly useless footage. The five days scheduled for the hunt grew into 22 as everything went wrong, including equipment breaking down in the extreme cold.

Bell also explains in detail how the magnificent eagle scenes were shot– what cameras were used and the techniques they developed out of necessity and lack of resources. Cameras attached to drones succeeded in giving us a sense of the eagle’s power and swiftness. A GoPro camera was attached to the eagle’s head using a small harness. Cinematographer Simon created a 9-meter lightweight crane that could be folded up and stored in a snowboard bag. The other ‘extra’ on the DVD is a 10-minute behind the scenes film, in which we see additional footage and get to see the filmmakers’ faces. From both we learn details about Aisholpan and her family and their way of life—the way the eagles are kept indoors with the family in bad weather, the ease with which the family take the ger down to move to their winter home, and how it was Bell’s fiancée who noticed Aisholpan’s purple nail polish in the footage from Bell’s first visit, and sent back fresh supplies (which we see Aisholpan sharing with her younger sister).

Cinematographer Simon Niblett, director Otto Bell and camera assistant Ben Crossley, with their driver and interpreter, observing camera on drone. Photo by Andrew Yarme, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

The Eagle Huntress has been well received in Europe and the U.S. It was introduced here at the Sundance Festival, noted as both a New York Times and an L.A. Times Critics Pick, nominated for many awards, winning some, and gaining good word-of-mouth as it was screened in theaters across the country. That is why I thought it was curious that the film also encountered something of a backlash. Some critics questioned the story’s veracity, a consequence, I think, of the film’s straightforward, simple story. Sometimes, truth is stranger than fiction. We know that. There were accusations that the eagle scenes were staged. Bell emphasizes again and again in his DVD commentary that the eagle scenes were filmed as they happened, and his detailed descriptions of the process and what went wrong and what went right and what they learned for the next time bolsters his story.

Camera assistant Ben Crossley shooting at the Eagle Festival. Photo by Andrew Yarme, Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics

Then, there were accusations from Adrienne Mayor, an independent scholar associated with Stanford, that Bell misrepresented Kazakh culture. In articles and online commentary, Mayor argues that there have been other female eagle hunters and that there is no prohibition against female eagle hunting in Kazakh culture. It’s always good to view a film with a critical attitude, especially a documentary, but I was struck by the unnecessary vehemence of Mayor’s critique. First of all, the claim that Aisholpan is the first eagle huntress derives more from the film’s marketing than from the film itself. Aisholpan does say that she wants to be the first eagle hunter in Mongolia, but you must keep in mind that this is a young girl living in a culture whose main source of news is the radio. She was most likely unaware of the two huntresses Mayor cites. The film’s marketing has been changed to focus on Aisholpan’s position as the first eagle huntress in her family and community.

Second, Mayor’s charge that Bell has exaggerated the sexism in Karakh culture probably came as a surprise to him. Like a good documentarian, Bell filmed what was in front of him and then arranged the footage to tell a story. Documentaries are not ethnographic research films, they are mediative realities, reflecting an individual’s perspective on a specific person or event. Bell allows his footage to show Aisholpan’s supportive family and, in contrast, the more traditional, dour elders. He gives a nuanced portrait of Aisholpan’s life with the school and dormitory scenes. It may be that Kazakh culture does not forbid women from being eagle hunters, but it is very clear from the footage itself that this is an exceptional event.

The Eagle Huntress is ultimately a story about a talented, determined, charismatic girl and her coming of age. It is also a film about Golden Eagles–their wild beauty and power of personality and grace of flight. I originally saw the film in a theatre in New York City with two birder friends, one of whom has a special love for and much knowledge about raptors. I was curious what Mary thought about the film, how much she thought was authentic. I was answered in one sentence. “Let’s go out and find us some Golden Eagles to take home!” The line was in jest, but the thought behind it was an enthusiastic appreciation of the film and its depiction of raptors. I thought the film in DVD format might be less of a thrill, but it is just as engaging and fascinating. The cinematography and editing are so well done that you feel the power of the eagle’s flight on the television screen. And, if anything, the small screen expands the power of Aisholpan’s smile. She is a heroine we birders can celebrate with optimism and pride.

The Eagle Huntress

Directed by Otto Bell; Director of Photography Simon Niblett

Starring Aisholpan Nurgaiv, Rys Nurgaiv, with Narration by Daisy Ridley

Music by Jeff Peters, title song sung by Sia.

Language: Kazakh with English subtitles

87 minutes

Produced by Kissaki Films & Stacey Reiss Productions

Distributed by Sony Classic

2016, DVD issued 2017, $22.98, discounts available from the usual sources; also available for streaming from Amazon Video and other streaming services.

Sony Classic Pictures web site for The Eagle Huntress has a history of eagle hunting and the Kazakh culture on its web site, and a Study Guide for teachers emphasizing the concepts of self-esteem, belonging, and gender equity.

Thanks to Sony Pictures Classic for allowing me use of film photos, before and behind the scenes.

Your article appears fairly well-researched but based on 6 years of following this story including its media-marketing shenanigans and articles like this one…All I can tell you is that once the truth comes out on what was left out of the film and the critical lack of veracity fact-checking, you and others will be very surprised. Gauranteed.