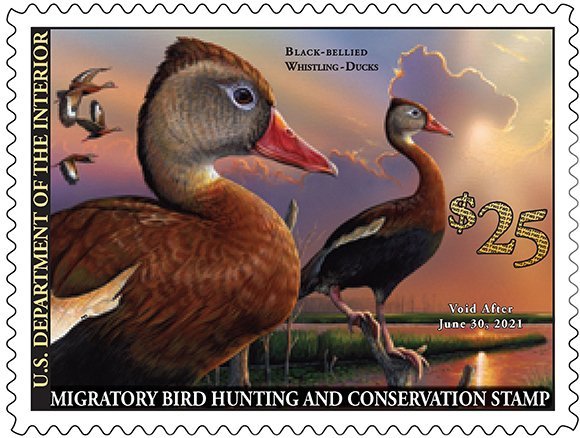

On June, 26, 2020, the 2020-2021 Federal Duck Stamp was released. Birders have been encouraged by the American Birding Association and others to buy Federal Duck Stamps. The argument is straightforward: birders buy stamps and the federal government turns around and obtains important bird habitat, no matter who is in the White House. Since appropriate habitat is both essential and quickly vanishing, the reasoning is that there there are few better ways to preserve birds.

But what kind of impact does it really have for birders? How important are 10,000 or 100,000 or even 1,000,000 acres and where are those acres anyhow?

In 2018, I posted a list of the 25 best National Wildlife Refuges for birding. And the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has published a list of NWRs that have been created or expanded with Duck Stamp funds. I compared the lists to see whether any land in the Top 25 refuges was obtained with Duck Stamp funds and, if so, how much.

The short answer is that Duck Stamp funds have contributed enormously to many of the Top 25 refuges for birding, including many of the marquee NWRs.

The longer answer is below. But initially, some background is helpful.

# # #

A “Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp,” more commonly known as the “Duck Stamp,” currently costs $25 and income from sales goes into the Migratory Bird Conservation Fund (“MBCF”). There are several sources for the MBCF, but two predominate: (1) Duck Stamp sales, and (2) import duties on arms and ammunition.

In fiscal year 2017, funds available to the MBCF totaled about $87 million. Duck Stamps and import duty contributions were similar, at about $34-38 million each. There was approximately $9 million carried over from the previous year and smaller contributions from a variety of other sources.

Acquisitions made with the MBCF are approved by the Migratory Bird Conservation Commission (“MBCC”). The members of the MBCC are set by law: the Secretary of the Interior, the Secretary of Agriculture, the Administrator of the EPA, two U.S. Senators, and two U.S. Representatives. Tradition dictates that the congressional members are divided evenly between Republicans and Democrats.

So Duck Stamp money goes into the MBCF and the MBCC decides how to spend those funds. To date (since 1934), the MBCF has either purchased or obtained conservation easements for approximately 6 million acres of habitat.

# # #

But what is the impact on the Top 25 NWRs for birding, and, by extension, birders? (For these purposes, we will set aside the obvious value of preserving habitat even if that land is not available for birding.)

The answer ranges from virtually everything to nothing, depending on the refuge. But broadly speaking, the impact of Duck Stamps is enormous. FWS reports include the overall size of a refuge in acres and the number of acres obtained with MBCF funds. From that, FWS calculates the percentage of the refuge obtained with MBCF money. This provides a rough sense of the importance of MBCF dollars to a specific refuge.

For example, Santa Ana NWR in Texas is a legendary birding location and it was in the news because the Trump Administration proposed building part of the border wall directly through it. (It received a reprieve, though surrounding areas did not.) Santa Ana NWR is relatively small at 2,087.50 acres, but 1,980.50 acres, or 94.9% of the entire refuge, was obtained with MBCF funds. In other words, virtually all of Santa Ana NWR was purchased with MBCF money.

This is hardly unique, as several others also have more than 90% of their acreage purchased with MBCF funds, including: Bombay Hook NWR in Delaware (95.2%), Bosque del Apache NWR in New Mexico (99.2%), Horicon NWR in Wisconsin (98.7%), Lee Metcalf NWR in Montana (96.3%), Parker River NWR in Massachusetts (97.7%), Pea Island NWR in North Carolina (99.2%), and Quivira NWR in Kansas (99.1%).

The list of NWRs from 80-90% is impressive as well: Anahuac NWR in Texas (80.0%), Edwin B. Forsythe NWR in New Jersey (84.3%), Laguna Atascosa NWR in Texas (86.3%), and Ottawa NWR in Ohio (83.8%).

Others are between 25.0% and 80.0%, including: Aransas NWR in Texas (42.7%), Chincoteague NWR in Virginia (69.9%), and Malheur NWR in Oregon (25.8%). Of course, there are some with little or no land purchased with MBCF funds, including Harris Neck NWR in Georgia (0.0%), Desert NWR in Nevada (0.0%), and Kilauea Point NWR in Hawaii (0.0%). A number of these NWRs were created with land transferred from other federal agencies, so the land was not purchased by FWS at all. For example, Kilauea Point NWR in Hawaii was created in 1985 with land transferred from the U.S. Coast Guard after the lighthouse there was deactivated.

Many of the NWRs that have received the most MBCF support contain hotspots in the eBird Top 100 in the U.S. (as to number of species in June 2020). They include: Hotspot No. No. 2 Bosque del Apache NWR (375, species and 99.2% of acres obtained with MCBF money); No. 3 Aransas NWR (367 species and 42.7% of acres obtained with MCBF money); No. 7 Parker River NWR (363, 97.7%); No. 10 Laguna Atascosa NWR (361, 86.3%); No. 22 Santa Ana NWR (348, 94.9%); No. 48 Anahuac NWR (331, 80.0%); No. 70 Pea Island NWR (322, 99.2%); and No. 72 Edwin B. Forsythe NWR (321, 84.3%).

In other words, some of the most popular and diverse marquee birding hotspots in America were disproportionately obtained with Duck Stamp/MBCF money.

A chart with the details for all of the Top 25 is below. While my Top 25 list is subjective and one might quibble at the margins, there is surely no denying the fact that many are among the most popular and highly-regarded birding locations in the country.

The bottom line for any conservation-minded birder is that many of America’s best birding locations would not exist or would be much smaller if not for Duck Stamps and the MBCF. Although the statistics do not address the quality of the land purchased or other qualitative factors, it is safe to assume that when it comes to protecting habitat, size matters.

# # #

My view is that every birder should buy a duck stamp every year. It is surely one of the cheapest and most effective avian conservation purchases a birder can make and it can be made annually. As an added bonus, Duck Stamps are tiny works of art and allow free admission to any NWR that charges a fee.

Top 25 NWRs for birding and percent of acres purchased with MBCF funds:

- Anahuac NWR (Texas): 80.0%

- Aransas NWR (Texas): 42.7%

- Bear River MBR (Utah): 36.9%

- Billy Frank Jr. Nisqually NWR (Washington): 56.3%

- Bombay Hook NWR (Delaware): 95.2%

- Bosque del Apache NWR (New Mexico): 99.2%

- Chincoteague NWR (Virginia): 69.9%

- Desert NWR (Nevada): 0.0%

- Edwin B. Forsythe NWR (New Jersey): 84.3%

- Harris Neck NWR (Georgia): 0.0%

- Horicon NWR (Wisconsin): 98.7%

- J. N. Ding Darling NWR (Florida): 7.4%

- John Heinz NWR (Pennsylvania): 8.1%

- Kilauea Point NWR (Hawaii): 0.0%

- Klamath Basin NWR Complex (California and Oregon): 0.0% to 44.6%

- Laguna Atascosa NWR (Texas): 86.3%

- Lee Metcalf NWR (Montana): 96.3%

- Malheur NWR (Oregon): 25.8%

- Minnesota Valley NWR (Minnesota): 0.0%

- Ottawa NWR (Ohio): 83.8%

- Parker River NWR (Massachusetts): 97.7%

- Pea Island NWR (North Carolina): 99.2%

- Quivira NWR (Kansas): 99.1%

- Santa Ana NWR (Texas): 94.9%

- St. Marks NWR (Florida): 42.5%

Photos: Signs by Jason Crotty; Duck Stamp by USFWS.

This post was originally published on August 14, 2018, and has been updated.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

New writers welcome – please contact us for details.

Would like to see someday just a Migratory Bird and Conservation Stamp–leaving out the word “hunting.” And our Secretary of Interior, Zinke, is looking to open up more refuges to waterfowl hunters and big-game hunters. Yikes! Hate the idea of watching a bird, aside from guns, smoke and dogs, knowing that it could become a cripple next week. “Why The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Is Problematic For Modern Wildlife Management.” M. Nils Peterson & Michael P. Nelson. 2016. {pdf} Also: North American Model: What’s Flawed, What’s Missing, What’s Needed.” Michael P. Nelson et al. 2011. {pdf}

Jeffrey and Jason,

It is easy to track the impact of duck hunters on habitat. Duck Hunters have a different set of operating principles in direct opposition to birders. My next film is taking a very direct look at this subject. Birders have a pitiful record of habitat conservation and literally should be ashamed.

I have been a birder since I was 4 years old, and in hindsight, this becomes more clear.

Thank you so much for posting the two pdf’s which are very instructive! I feel the future is being clarified, but the instruction manual is missing or not being read.

There is no reason to not have a Federal Birder Tax, Birder Stamp and to have an expanded Am. Bird Conservancy program. If birders want to have a say- we need to pick it up now. Saving both ends of the habitat required for migratory species like a Cerulean Warbler is a complex set of problems. So we need to address these in a comprehensive manner.

Popular birding is simply not engaged enough with habitat. Comparing a Duck Unlimited banquet to an Audubon Society tea is ridiculous. National Audubon has done nothing in comparison to DU.

Please note- I am NOT a hunter at all. Period. But DU is now undertaking a $1 Trillion dollar effort to save Boreal forest habitat in Canada. There will be more Magnolia Warblers, more Bay-breasted Warblers habitat saved from this effort than any Birder led effort which I am aware of.

Passing everything off to the government or USFWS is a dangerous precedent. DU does press Federal agencies too, but put up millions to match and works as a more effective leader.

IMO- this is the problem.

If Birders want influence, we have to address power. Money is power.

We are in a time of great change. Let’s not waste it.

Timothy– I agree, in part, to your comments. It depends on what one defines as a “birder.” Audubon was a birder, and so was Teddy Roosevelt. And so is the person today who goes to Central Park to bird on weekends. In recent decades, birders have lost much of a conservation ethic. A quote from A SHADOW AND A SONG: The Struggle to Save an Endangered Species (Mark Jerome Walters 1992) “A life-long birder, Kale was saddened by the sudden loss of interest [Dusky Seaside Sparrow relegated to subspecies status]. Many birders, he realized, were not so much supporters as collectors. Many birders are often not so much lovers of birds, as lovers of lists….” As for DU, their goal has always been strictly for human-centered fulfilment (conserving habitat for the sport of killing). True, DU and sport hunters have saved habitat (especially wetlands), but the difference has always been between those who strive to preserve nature and species for their own fulfilment, and those who want only to exploit it. By the Way, we are living in a time of great change–with the present administration we’re going backwards fast.