The introduction of the Merlin Bird id app by Cornell University has had a huge impact on birdwatching. Downloading the app on your telephone is free, while it’s easy to use, not only identifying the birds that it hears, but also providing a photograph of that bird (obviously not that individual), plus information about the particular species. The app works in many countries, including all of Europe and North America. At the time of writing it has 1724 supported birds.

Merlin is a simple app to use

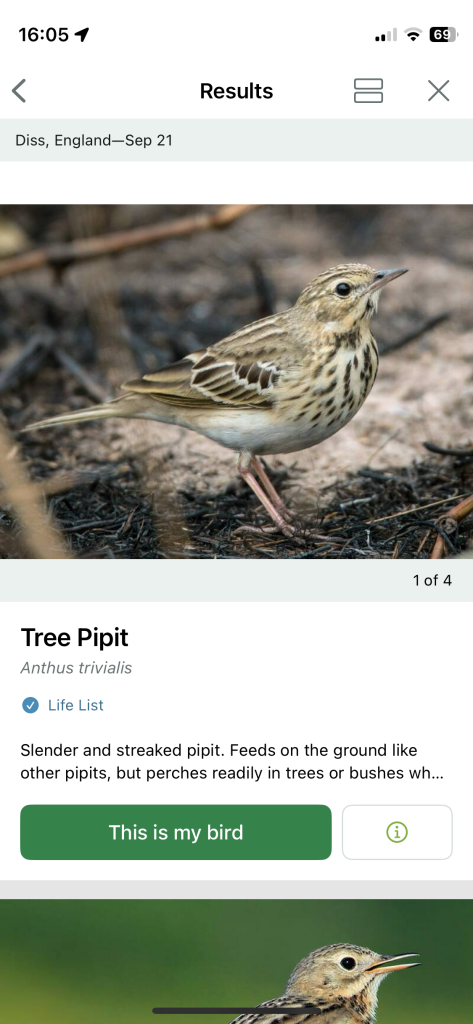

It will also identify birds from a photo you have just taken, or one from you photo library. A few details are needed, such as where and when the photo was taken, then you just press the identify button and within seconds the bird will be named for you, though alternative possible species will also be provided. However, if your photograph isn’t clear enough, it will respond with “Merlin doesn’t have a likely bird”, which is fair enough.

Merlin successfully identified this Jungle Babbler

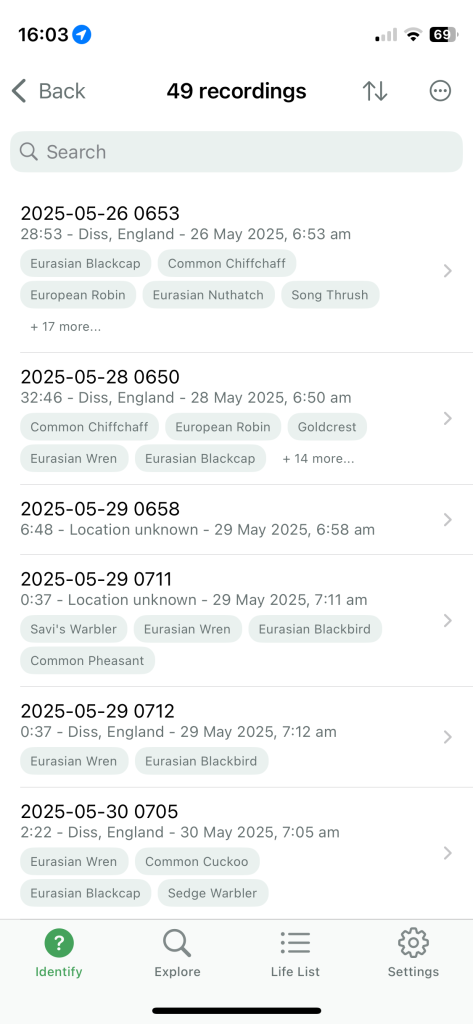

I’ve used Merlin extensively in the field to identify bird song and calls, and have been hugely impressed with its ability. It not infrequently picks up birds before I do (and I’m not bad at identifying birds by ear), while it’s also useful for confirming birds that I have heard. Of course, it does make mistakes, but that’s hardly surprising in view of the fact that certain birds have very similar voices to each other. Never forget that artificial intelligence isn’t infallible.

Merlin does register your location, so it usually knows where you are, though it sometimes struggles with this presumably due to a poor signal. If you are using it in England and it hears a Marsh Tit it’s unlikely to tell you that the bird is a Black-capped Chickadee, as the geographical location rules the latter out. I was once birding in a huge quarry in northern Greece where I was hoping to find European Eagle Owl. Merlin claimed to have heard one, though I was never able to confirm it. My suspicion is that it was right, as it didn’t know that I was in suitable habitat for an Eagle Owl, or that this was a bird that I was looking for.

It’s mistakes are usually obvious. On one occasion, in my garden in England, it registered a Tropical Kingbird, a bird I know from the American tropics but which has never been recorded in Europe. Curiously, my Merlin not infrequently comes upon with Savi’s Warbler, despite the fact that there’s not the slightest possibility that there’s a singing Savi’s within 100 miles of me. Friends using Merlin at the same time have never come up with a Savi’s, so why does mine?

A test of Merlin’s ability to identify a bird: it correctly named the Tree Pipit

Merlin is definitely better on songs than calls, which you would expect, as many calls are similar to each other. If it does come up with an unlikely suggestion, the best thing is to try and see the bird yourself so you can visually identify it. Sometimes it totally ignores a nearby call or song for reasons best know to itself – very frustrating.

Never use Merlin if you are undertaking a bird survey. The British Trust for Ornithology states that “you should not solely rely on the Merlin Bird ID app for submitting data to BTO surveys; instead, use the app for identification and then confirm the bird’s identity by sight or sound in the field before recording it in your BTO survey data, such as BirdTrack. The BTO cautions against using auto-identification tools as the sole basis for data records because they can sometimes be inaccurate.”

One of the best things about Merlin is that has inspired many thousands of people to take an interest in birds. I know lots of people who certainly wouldn’t describe themselves as even amateur birdwatchers who enjoy using Merlin. Identifying a singing bird is a certain catalyst for taking a greater interest in birds in general, which has to be a good thing.

I’ve never had good luck with Merlin. Downloaded it the first time I was headed to the Solomon Islands (which, to be fair, was an unfair baptism) and it didn’t help me at all. Tried it in Kenya and it also came up blank. At home in Trinidad it seems to know more and can pick up a few species but I don’t ever use it here unless I’m demonstrating how to use it.

Mimics throw Merlin off the scent but it is a good app. I use it like David does but never for the primary id. It definitely needs to get better in the tropics although Faraaz was pushing it with the Solomons…

David does a great job with this question. Agree with him on the never uses and the great value it has added to birding. Even non-birders have the Merlin app on their phones. Merlin is getting better and better all the time and, if you are birding in, say the US, it’s likely to be enormously accurate. But it still gets things wrong and non-birders may not necessarily know when that happens. As Faraaz points out, Merlin was completely unhelpful to him in places where it was unlikely to have adequate data to scrub from. As Peter suggests, Merlin can be thrown off course by different sounds. Birds make all kinds of calls and many have a variety of songs too. I use it for calls or songs I hear, but which I cannot bring to memory.