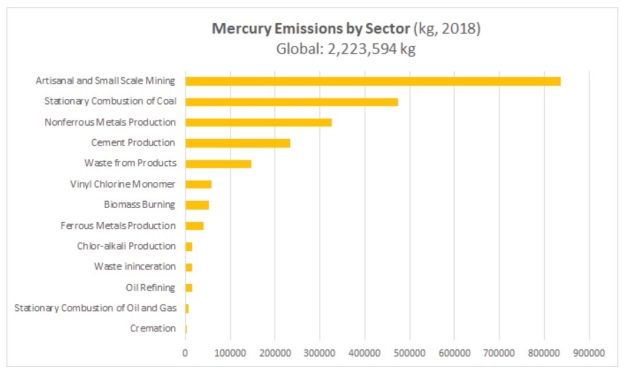

Human activities, such as mining, coal burning, metal production, and cement production, lead to the release of large amounts of mercury into water.

Source: EPA

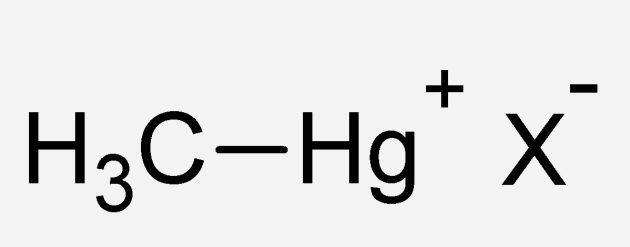

Anaerobic bacteria in wetlands and sediments then convert inorganic mercury into methylmercury, a highly toxic, fat-soluble organic compound.

Methylmercury bioaccumulates – invertebrates are eaten by small fish, these are eaten by larger fish, which are then eaten by fish-eating birds such as herons, loons, ospreys, eagles, and penguins. So, the animals at the top of the food chain get the highest doses. Other bird families, such as shorebirds and ducks, ingest mercury by foraging in contaminated mud.

In the avian body, the methylmercury forms complexes with the thiol groups in proteins (i.e., with cysteine residues, as these are the ones with thiol groups).

Depending on what the function of the proteins is, this causes different types of damage:

- When binding to structural proteins, mercury can alter folding or stability, leading to misfolding and aggregation.

- When binding to transport proteins (proteins that transport amino acids in the body), mercury changes amino acid availability

- When binding to hemoglobin, mercury changes the oxygen transport efficiency

- When binding to enzymes, mercury destroys the catalytic activity of the enzyme. This is generally regarded as the most serious effect of mercury. For example, binding to glutathione peroxidase impairs the antioxidant defense, while binding to thioredoxin reductase disrupts redox regulation. These failures then have consequences such as cell damage.

Apart from the damage caused by this binding to proteins, mercury also catalyzes the production of reactive oxygen species. These are unstable molecules that contain oxygen and easily react with other molecules in a cell, which may cause damage to DNA and RNA.

Finally, mercury disrupts the selenium biochemistry as it forms mercury-selenium complexes. The resulting depletion in selenium weakens antioxidant defenses in the avian body.

All these chemical reactions have effects on the health of the bird:

- Neurological effects: Methylmercury leads to poor coordination, tremors, reduced foraging efficiency, and impaired vision, thus making it harder to catch prey or avoid predators.

- Reproductive toxicity: Methylmercury reduces egg production and hatching success. Embryos exposed to methylmercury often die early or develop deformities.

- Hormone disruption: Methylmercury affects hormone regulation, which may weaken the immune system

- Behavior: Methylmercury may lower parental care and reduce singing

Birds have one defence mechanism – some store mercury in their feathers, where the mercury binds to the keratin (which has many thiol groups). This deposition in the feathers lowers the mercury content in the body. Analyzing feathers also allows for determining the mercury exposure of birds without killing them.

Larger fish-eating birds (Common Loons, Bald Eagles, Ospreys), shorebirds (sandpipers, Dunlins, etc.), and terns/gulls are among the most affected bird species and families affected by mercury.

Photo: Osprey, Nanhui, Shanghai, November 2019

Not good for human brains either. Mercury is nasty and the most immediate effect of burning coal isn’t climate change, but mercury poisoning.

After German reunification, environmental pollution in the former GDR (East Germany) was investigated. I provided several molted feathers from ospreys for this purpose. Very high concentrations of methylmercury were found in them. At that time, agricultural seeds were treated with fungicides containing methylmercury.