By Peter Hinow

Originally from Dresden, Germany, Peter Hinow is a mathematics professor at the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA. One day, when left unsupervised at home, he toyed around with a 300 mm lens that his better half had bought as part of a camera package, and which had sat several years unused in its original box. It turns out, they can make distant objects appear closer! The first “victim” was an American Robin (Turdus migratorius), and the list has only been growing ever since.

The book under review is published by MIT Press, the publishing house of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. To me, this suggests that the target audience of this book is professional ornithologists and behavioral scientists. A general “birder, scientist, or student” (from the preface) will find this book enjoyable, but must be willing to put in quite a bit of extra legwork. I certainly noticed where I benefited from being a mathematician. The authors are eminent neurobiologists and behavioral scientists with impressive records of field work and publications in peer-reviewed journals.

The book begins by placing the birds into a phylogenetic tree of living amniotes, a clade that comprises most living terrestrial animals. Birds are, as every parent who has taken their kids to a natural history museum will remember, dinosaurs. Next is shown the phylogenetic relationship of the approximately 10000 bird species that are known today. An important fact that is pointed out more than once is that “basal” does not equate to “primitive”. Birds are known to have a relatively large encephalization, which is, roughly speaking, the ratio between an animal’s brain size and its body size. There are many diagrams showing the anatomical organization of bird brains and the pathways connecting the different regions (Figures 1.8-1.13). One would wish for more explanation about the relevance of this organization and how it contributes to the greater intelligence of birds compared to reptiles.

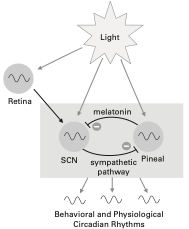

Reproduction of Figure 2.4 on the circadian rhythm.

Chapter 2 discusses daily and seasonal rhythms and how they affect birds’ (and more generally, animals’) behaviors. As an example, I am reproducing here Figure 2.4, which shows a directed graph with pointed and blunt arrows. I have the advantage of having seen such pictures before and, in fact, even worked with them in my own research. This is what I mean when I say that an uninitiated reader may have to use quite a few additional resources to follow the story here. Pointed arrows generally stand for excitatory pathways, while blunt arrows stand for inhibitory pathways, and this is true in both biochemistry and neuroscience.

Chapter 3 treats the problem of locomotion and motor control, and it is here that I had my first moment of fascination. Think about the following “engineering” problem: on the one hand, you want to be able to control the legs in a “standard” pattern alternating between the left and the right side, moving forward while the other side stays put. On the other hand, the wings should always move in synchrony. Although there are many open questions and this is an active field of research, the ingenious solution is that birds apparently have a different spatial organization of their spinal cords in the cervical and lumbar regions, respectively. A part of the separation between the two body sides falls to the mysterious glycogen body, a structure that is unique to birds and whose precise role remains unknown.

The book is written in a clear and engaging style. I appreciate the simple, yet profound comparisons drawn with tasks that other animals (e.g., us, Homo sapiens) face. For example, if we want to walk straight, we mainly must keep an object in the center of our visual field in place. A bird with its eyes oriented laterally has a different problem to solve to fly straight: it must ensure that objects on either side pass at the same rate. In this sense, birds move “through” the world and not “into” it, as we do. At least occasionally, I may ask myself how my brain “knows” that I am correctly positioned on my bicycle or similar things.

Beyond the chapters that were reviewed here in detail, the book contains chapters on homing, migration, feeding, sex and social behavior, birdsong, cognition, tool use, and the relationship between humans and birds. It is very clear that humans have many and mostly negative impacts on wildlife, including, for example, that domesticated birds have a smaller brain size (relative to body weight) than their wild counterparts. The book ends with a long list of references and links to videos. At the end of this review, here is my personal obsession in every scientific text I read: the use of imperial measurement units. Yes, this book is probably written mostly for the American market, but even for this readership, feet and miles should no longer be used. It is even more puzzling that body weights are listed correctly in grams. All in all, I enjoyed reviewing this book.

Publisher: The MIT Press

Publication date: August 5, 2025

ISBN-13: 978-0262552738

Leave a Comment