Joan Strassmann’s book starts with a message of hope to all of us birders who, to some extent, believe – or are being made to believe – to be nerds:

“Bird-watching has a rather staid reputation, in which the birder is thought to be a quiet, bookish observer, carefully noting species and habitats with the quasi-academic bent of an ardent plane-spotter. But unlike planes, birds are social, and their lives are full of drama, intrigue, cooperation, and competition. They skirt danger, form couples and communities, sneak around and steal, and flirt like their lives depend on it. All this makes bird-watching fascinating—more like picking up a juicy beach read or tuning into a thrilling miniseries than recording the airplane tail numbers at a local runway.”

Thus morally supported, the birder – whether a social person or not – can start learning about the social lives of birds*. And there is a lot to learn from this book, both about the topic itself and about the scientists and the research involved in uncovering it. To illustrate this, I will just pick one example for each of the topics dealt with in the ten main chapters of the book, all illustrating different aspects and (mostly) benefits of being social:

Flocks: Common Redshanks in the UK are safer from attack by sparrowhawks, particularly if they stay close to other redshanks.

Roosts: Bushtits roosting together at night lose less weight than those roosting alone, as staying together reduces heat loss.

Mixed Species Flocks: Here, Strassmann highlights the importance of nuclear birds – those birds at the core of mixed flocks, which give the loudest warning calls when they perceive nearby predators. She also points out the increased vulnerability of such mixed-species flocks to environmental disruptions.

Bird Colonies: Despite greater competition for food and greater risk of disease, birds such as Bank Swallows nest in dense colonies, as this gives greater protection against predators, partly via mobbing.

Seabird Colonies: Similarly, in birds such as Common Guillemots, denser colonies reduce the predation risk for individual chicks.

Leks: Having all male Greater Sage-Grouse at the same location allows the females to shop for the best.

Parental Care: Here, Strassmann describes early research on sterilizing male Red-winged Blackbirds – and the surprising finding that the pairs with sterilized males still yielded chicks. Nowadays, genetic testing allows much more specific insights into infidelity among birds.

Helpers: An interesting fact I learned in this section – looking at increased nesting success among Florida Scrub-jays with helpers – is that the improvement came less from better provision of food and rather from a decrease in predation. The helpers reduced predation by warning of approaching danger, which then allowed for joint mobbing.

Communal Nesters: This was perhaps the most surprising chapter for me, describing how several pairs of birds, such as Groove-billed Anis, share a single nest. Not without conflict, though – while some incubation and feeding duties are shared, eggs are being tossed out as well.

Supersocial Groups: This is another fascinating aspect of the social lives of birds such as Acorn Woodpeckers or Social Weavers. For the latter, each family has its own separate dwelling, but all are responsible for the enormous superstructure that contains the individual nests.

Having read such a dry list of facts, you will wonder whether Strassmann writes in the same style. Fear not. Not having a background as a management consultant, she writes in a much friendlier tone, weaving in personal bits such as a visit to her daughter or spending a year in Berlin.

That also means that occasionally, Strassmann falls into the “wide-eyed and wondering” tone that I personally do not like very much, though I am sure many readers of 10,000 Birds will disagree with me on this. I am thinking of passages like “Wake up to flocks and you will start to see them everywhere, from the ducks in a city pond to the chickadees or tits hunting for insects deep in winter. From now on, I hope you’ll look at them just a little bit longer and with a little bit more wonder.”

But that does not make the book less worth reading. Strassmann has collected an enormous amount of research on the social lives of birds and summarizes it in an entertaining and accessible way. If you have any interest in the social lives of birds and do not want to delve into hundreds of original research papers, then this is the book to read.

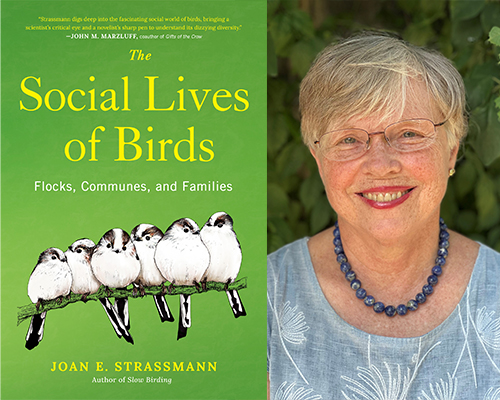

From the press release: JOAN E. STRASSMANN is an award-winning teacher of animal behavior, first at Rice University in Houston and then at Washington University in St. Louis, where she is Charles Rebstock Professor of Biology. She has written more than two hundred scientific articles on the behavior, ecology, and evolution of social organisms. She is a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a fellow of the Animal Behavior Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and has held a Guggenheim Fellowship. She lives with her husband in St. Louis, Missouri, and Leland, Michigan.

The Social Lives of Birds

Joan E. Strassmann

ISBN 9780593853061

Published September 23, 2025

Tarcher

*At this very early point of working on the review of her book, I got sidetracked by a related question: Are birders more or less social than average adults? Not wanting to spend serious research on the question, I asked ChatGPT, only to get a rather inconclusive answer: “In comparison to average adults, birders tend to be more socially active within the context of their hobby—through citizen science, group outings, online platforms, and shared passion. That said, many also cherish the solitude birding can offer, and their overall social orientation outside of birding varies.”

Leave a Comment