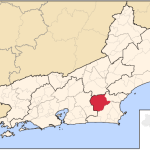

Rather more than half a century ago I visited Spain’s Ordesa National Park for the first time. Established way back in 1918, today the park is known as the Parque nacional de Ordesa y Monte Perdido. Its size has also been increased since my initial visit, and it now covers over 150sq km (60sq miles) of spectacular mountain scenery. Limestone is the dominant rock, and there are huge cliffs, impressive canyons and fabulous mountains. Monte Perdido (the lost mountain) is the tallest peak in the Pyrenees, reaching 3,355m (11,007 ft).

The view towards Monte Perdido

My first visit wasn’t to admire the scenery, as much as I enjoyed it, but to try and see a Lammergeier or Bearded Vulture. I was in company with two other teenage birdwatchers, and we were driving home from visiting Spain’s Coto Doñana National Park. At the time Lammergeiers were extremely rare, the Pyrenees their last sanctuary in Spain. I’m not sure how many pairs remained then, but I do know that in the late 1980s there were thought to be a mere 40 pairs in the whole of the Pyrenees.

We didn’t know anyone who had seen a Lammergeier in Ordesa, and we had also heard that these giant vultures were rarely seen from public roads, so we weren’t optimistic when we arrived in the park and scanned the cliffs that towered above us. It was mid October, and there was a distinct autumnal chill in the air: Monte Perdido was already capped with the first snow of the season. Our chances of success didn’t look good.

A Lammergeier high overhead. The diamond-shaped tail is distinctive

However, we succeeded against the odds, gaining fine views of two birds that soared and flapped over the valley, looking more like giant falcons than vultures. The flight silhouette of the Lammergeier is unmistakable, with its narrow, pointed wings and long, diamond-shaped tail. There’s nothing else you can confuse it with. That first view was made all the more memorable by the low October sun illuminating the birds’ buffy, almost orange underparts. We often talk about unforgettable views: this was one.

Quebrantahuesos – a portrait of a Lammergeier, by Timothy Greenwood

One of my companions was a young man called Tim Greenwood: he went on to make a successful career as a wildlife artist. Tim later gave me a watercolour portrait of a Quebrantahuesos – a bone-breaker, which hangs in my study today, a delightful memento of that first sighting.

Mountain bird guide Alberto Marin from Senderosaordesa

I was reminded of all this earlier this month, when I made my first visit to Ordesa for several years. I had the opportunity to go high above the tree line, something that I’d never done before. This was thanks to my guide, Alberto Marin, and his 4×4 VW minibus. Alberto collected me and my companions in Aínsa, and from there he drove us north up the valley of the Rio Cinca to Bielsa, shortly afterwards turning off onto a permit-only gravel road that wound its way high into the Sierra de Liena.

Alpine Marmot, a common mammal above the tree line. We also saw Chamois

We were lucky, as the previous day’s cloud and rain had moved on, leaving a cobalt blue sky empty of clouds. Later, the clouds did creep back, but for the first few hours we enjoyed brilliant sunshine illuminating what is one of the finest mountain landscapes in Europe. We had clear views across to Monte Perdido. There was no snow on the mountain, but we could see its glacier, a feature that is melting fast and seems unlikely to survive for another decade.

Juvenile Northern Wheatear. In summer these wheatears are one of the commonest birds above the tree line in the Pyrenees

Alberto had explained that September isn’t the best of months for finding birds in the high Pyrenees, for many of the breeding birds, like Red-backed and Woodchat Shrikes, had already left. There were, however, still plenty to see. Northern Wheatears, one of the commonest breeding birds here, flew in front of our van. We had to look harder for Water Pipits, as most had already left the high tops, but there were still a few around. Alpine Choughs were elusive but finally revealed themselves.

A juvenile Rufous-tailed Rock Thrush. The rufous tail is conspicuous when the bird flies (Photographs courtesy Richard Hanman)

One of the loveliest of alpine birds is the (Rufous-tailed) Rock Thrush. We weren’t lucky enough to spot any adults (they had probably already left), but there were a number of scaly-plumaged youngsters to be seen and enjoyed (above). Another red-tailed bird that was common was the Black Redstart, here of the handsome Spanish race aterrimus, which has jet-black as opposed to grey plumage.

A Black Redstart of the race aterrimus

End of the road at almost 3000m: time to hike in search of Wallcreepers

We eventually reached the point where we could drive no higher, so it was a matter of hiking to a vantage point where, Alberto told us, we should see Wallcreepers on the facing cliff. It was a stiff climb, culminating in a path that traversed a scree slope – I was glad of my stick, as I’ve never had a head for heights. However, Wallcreepers hold a strong lure, so I was prepared to put some effort into seeing them. I have been lucky enough to have encountered these delightful birds many times since my first in Ordesa in September 1976. As we scrambled to our commanding view point, a fine adult Lammergeier soared over.

On top of the world. The author in a grand mountain setting

Wallcreepers may be distinctive, but they are very small birds, and we were sitting facing a huge cliff face. We’d been watching for some time before my companion Chris Collins gave a shout: he’d spotted our quarry, and had two birds in view. We all eventually managed to see them – there were three individuals – but frustratingly they were so distant that it was only their behaviour and movements that identified them, and we never even glimpsed the crimson in their wings.

Wallcreeper: one of the most sought-after of Pyrenean birds. This was not one of the birds we saw – they were too distant for photography

In summer Wallcreepers are birds of the high tops, favouring sheer cliff faces where they are always a challenge to see. They are much easier to find in winter when they drop to lower altitudes. On one memorable trip I saw seven different birds in two days in the Sierra Guara, the pre-Pyrenean mountain massif just a few miles from where we were watching. This is almost certainly the easiest place in Spain to see these delightful birds, with March the best month.

Alpine cattle graze the high pastures in summer, but are brought down from the mountains in the winter

Mountain birding is never easy, and there are always birds that you hope to see but fail to find. Alberto told us that the scree we had walked across was a good site for (Rock) Ptarmigan. The tiny and isolated Pyrenean population here is reckoned to be a relict of the Ice Age. It’s a bird I’ve only ever seen in Scotland and Norway, and I still haven’t seen a Spanish bird. Nor did we manage to find an Alpine Accentor, another bird of the high tops that drops to lower altitudes in the winter.

A juvenile Honey Buzzard, heading south (Photograph courtesy Richard Hanman)

However, frustrating though it was to miss such good birds, there were compensations, such as the juvenile Honey Buzzard photographed so well by another of my companions, Richard Hanman. Our lunch of local cheese and meats, with fresh bread and a glass of vino tinto, was memorable not only for the food and the fantastic scenery, but also the pair of Golden Eagles that soared overhead. We ate surrounded by a herd of placid cows, their bells providing an evocative background soundscape. There are few finer places to look for birds than Spain’s Parque nacional de Ordesa y Monte Perdido, though it helps considerably to have a good guide and fine weather.

The distinctive silhouette of a Golden Eagle. The blue sky had gone, and the clouds were now obscuring the high mountain tops

Our specialist birding guide in Ordesa was Alberto Marin. Email him at info@senerosordesa.com, or look at his website: https://senderosordesa.com/. For more information on birding in Aragón, go to https://birdingaragon.com/en/birding-aragon/. There is a wide choice of accommodation in the area. I stayed at O Chardinet d’a Formiga, a charming guesthouse based in a beautifully modernised 17th-century farmhouse. The hospitality was as warm as the cooking was good, while birders are specially welcomed.

Great read thank you

Wallcreeper is such a great bird. I’m glad you saw it. Agree, too bad it was not closer for you. I am surprised to read that Rock Ptarmigan can be found in the Pyrenees. It seems so unlikely. The Lammergeier a very nice sighting and nicely photographed. I’ve only see on TV nature shows.