Long-distance migration requires birds to reliably determine the correct direction. They use many cues, including the position of the sun, stars, coastlines, and other familiar landmarks. In addition to these, a substantial body of research shows that many species can detect Earth’s magnetic field and use it for orientation. This post outlines the chemical mechanism currently considered the most likely basis of this magnetic sense.

Evidence for magnetic orientation

Studies on species such as the European Robin demonstrate that birds maintain directional orientation even when exposed to experimentally altered magnetic fields. When researchers shift the magnetic field around the birds, their preferred migratory direction shifts accordingly. The effect persists even when other cues are removed, indicating the presence of a dedicated magnetic sensing mechanism.

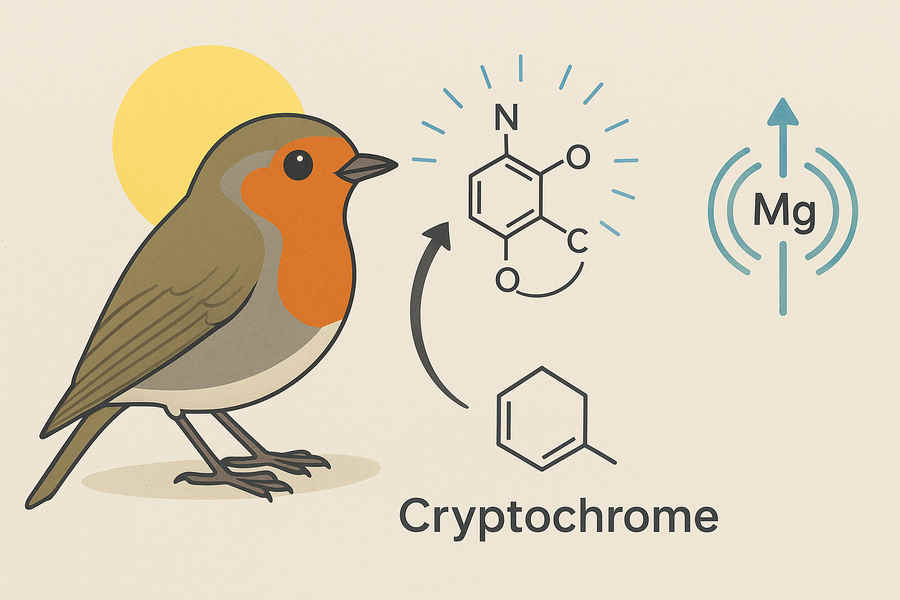

Cryptochromes and radical-pair chemistry

The leading explanation for this ability involves cryptochromes, light-sensitive proteins located in the retina. When cryptochromes absorb blue light, they can form “radical pairs”—molecules with unpaired electrons. These electrons can occupy different spin states, and transitions between those states are influenced by weak external magnetic fields.

Because the chemical reactions that follow depend on the electrons’ spin states, changes in Earth’s magnetic field can alter the reaction outcomes. This provides a plausible biochemical pathway for detecting magnetic information.

Processing magnetic information

The way the nervous system interprets these chemical changes is still being clarified. Current models propose that variations in cryptochrome reaction products are processed in visual pathways, effectively adding directional magnetic information to the bird’s sensory perception. Several experimental findings support this hypothesis:

- Magnetic orientation in many species requires dim blue or green light and does not occur in complete darkness.

- Disrupting cryptochrome activity interferes with magnetic orientation.

- Low-level radio-frequency noise, which can affect electron spin transitions, reduces orientation accuracy in controlled studies.

Together, these observations strongly support the involvement of radical-pair reactions in magnetoreception.

Significance of the chemical mechanism

If the radical-pair mechanism is indeed responsible for magnetic sensing, it represents a rare case in which quantum-level chemical properties have a functional role in animal behavior. Because cryptochromes are found widely among birds, this mechanism may apply across many species.

What remains unknown

Several aspects of avian magnetoreception remain unresolved. These include the precise neural pathways that convert cryptochrome-based chemical changes into directional information, the degree to which different species rely on magnetic cues, and how magnetic information is integrated with visual, olfactory, and spatial cues during navigation.

Nevertheless, current evidence points to a light-dependent biochemical process in the eye as a key component of the avian magnetic compass. This makes magnetoreception a clear example of how chemical reactions can underlie complex and large-scale behavioral patterns such as migration.

Note: Birds have a fourth cone type sensitive to ultraviolet light, but current evidence indicates that this plays no role in their magnetic sense. Magnetoreception relies instead on cryptochrome, which is activated primarily by blue light.

Leave a Comment