Is Cordelia Cupp the birder we have been waiting for? The cinematic representation of our passion, presented to the world as both the smartest person in the room and the quirkiest person in the building? Is this how we look to the world? Is this how we want the world to see us? Let’s talk a bit about The Residence and other representations of birders (and birding) in film and television.

The Residence is an eight-episode mystery-comedy-drama miniseries created by Paul William Davies, produced by Shondaland, currently streaming on Netflix (my apologies to readers who don’t or can’t subscribe, hopefully it will be available through other venues in time). Cordelia Cupp, played by the incomparable Uzo Aduba, is the star and the heart of The Residence. A world-famous “consulting detective,” Cordelia Cupp is an African American, 40-something years old woman called in to investigate the death of Chief Usher E. B. Whyte. Like her literary and film predecessors (think Sherlock Holmes, the original consulting detective, Hercule Poirot, Benoit Blanc, Lord Peter Whimsey and Harriet Vane combined), Cordelia is quietly confident, unintimidated by powerful people, and solves mysteries with original thought and brilliant analysis. She’s dressed in colors of brown and beige–a British hunting jacket over a V-neck sweater over a shirt that may have little birds on them, with Katherine Hepburn-type pants, and sensible brown brogues. She swings a weathered leather satchel, capacious enough to hold a very large book about birds and a small notebook, which she uses for both birds and to solve mysteries.

© Netflix, 2025

We know Cordelia Cupp is a birder immediately because, rather than immediately going into the White House to examine the body, she birds the White House grounds. We first see her from the White House balcony, where a group of men are incredulously watching her birding in the dark, her face obscured by binoculars. Cordelia walks in full of excitement at seeing two birds on Theodore Roosevelt’s White House bird list, an Eastern Screech-Owl and a Purple Grackle (stretching out the word ‘graakkkllle’ so we too pay attention), before seamlessly transitioning to a silent but intense examination of E.B. Whyte’s body. (She does take a moment to look at the self-important men in the room and say, to the joy of women everywhere, “Wow. It’s a lot of dudes.”). It’s not clear whether Cordelia has agreed to take on the case because it’s an intriguing challenge, or as a favor to her friend, the metropolitan police commissioner, or because it gives her an opportunity to see the birds on Roosevelt’s list, but given her change of demeanor from pure excitement over the Purple Grackle (the name Roosevelt would have used at the time) and her businesslike concentration examining the body and the room, my money is on the latter.

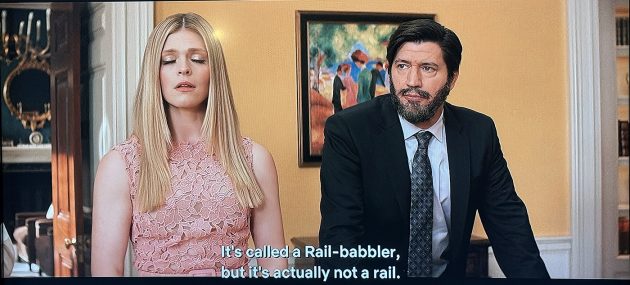

This is the first of many scenes that involve birding, to my mind authentic (mostly) and often humorous. There are bits of insider birder dialog, like when Cordelia talks to real-life birder and author (and consultant for the series) Kenn Kaufman about the birds she saw and missed in Colombia. Sadly, we don’t hear Kenn at the other end of the satellite phone (Cordelia does not own a cell phone), but she does identify him after her phone conversation as the finder of the first Pale-footed Swallow for Venezuela–a bit of trivia I did not know. Moments of humor play on the differences between how birders and non-birders do things, as when Cordelia uses her binoculars (I think Swaros) to examine the dress shirt worn by an Australian diplomat (he’s handsome, but Cordelia is more interested in evidence that it isn’t his shirt). Sometimes it’s a bit of both the authentic and the comic, such as when Cordelia gives her definition of sex to the Australian diplomat (the one she was examining with her bins): “I define it as the thing I enjoy more than talking about real estate and less than looking at birds.” (Don’t deny it–we have all had this thought.) My personal favorites are the bits when White House power players become totally exasperated with Cordelia’s bird-mind, such as when White House insider Harry Holloway shouts, “Can we not with the f****** birds this time. Enough with the f****** birds!” Look at the screenshot below and tell me you don’t have friends or family that look like this when you mention birds.

From Episode 8, © Netflix, 2025

More nuanced are the birding scenes that give insight into Cordelia Cupp’s character and personal history. In episode four, on the beach of an unnamed island in French Polynesia searching for a Tuamotu Sandpiper, she has a conversation with her young nephew Ansel that may sound familiar:

Ansel: “We haven’t seen any birds.”

Cordelia: “We have seen birds. We haven’t seen THE bird.”

Later, Ansel: “What if we don’t find the bird?”

Cordelia: “We’ll find the bird.”

Ansel: Have you ever given up?

Cordelia: No.

Ansel: Never?

Cordelia: No.

Ansel: Never?

Cordelia: No.

Ansel: Never?

Cordelia: No.

Ansel: Do you ever think this is unhealthy?

Ansel’s mother, Cordelia’s beloved sister, thinks her birding passion is single-minded and obsessive. We can relate.

The genius of the script is that these core birding attributes are also what makes Cordelia the world’s greatest detective. She is highly observant, has an incredible memory for detail, listens—really listens to people (and birds and background noise), and has enormous amounts of patience. She also knows her birds, and continually cites examples of bird behavior to prove a point. Sometimes the metaphors a little convoluted—the Mountain Chickadee’s near perfect recall of every place they’re cached their 80,000 seeds somehow relates to people’s ability to remember things important to them, including “the things we have hidden inside,” which somehow relates to the secrets of certain murder suspects is a prime example—but we accept it because we’re birders and Cordelia Cupp is very confident and very convincing and carries around that big bird book. (The book itself is a clever fake, utilizing the lovely birdy cover design of Birds of the World by Les Beletsky but with different birds and a different author, Wendell Phillips, who in real life was an abolitionist. Interestingly, Kenn Kaufman wrote a blurb for the Beletsky book.)

There are a few snafus that birders have cited in social media and interviews. There is that large bird book–wouldn’t Cordelia have been more likely to carry a field guide? Also, it would have been very difficult for Cordelia to identify a Purple Grackle or a Song Sparrow in the dark, these birds are unlikely to be active at that time (and–it’s dark). The falcon featured in the opening of episode two looks CGI-created and is not quite a Peregrine Falcon, nor is it identified as one, it’s simply called “a falcon.” And why is the Giant Antpitta Cordelia’s nemesis bird, why didn’t she simply go to Ecuador and see one at Refugio Paz de las Aves, where they feed out of the hands of Angel Paz and his family?

Kenn Kaufmann addresses most of these criticisms in an article in Audubon Magazine . He basically says that Cordelia was birding in the dark was necessary because of story dictates, the falcon is a “metaphor,” and that he thinks Cordelia was searching for the Giant Antpitta on her own because she didn’t want to see it the easy way, an explanation that really does reflect her character: “Sometimes you have to suspend disbelief just a little. The Residence is a work of fiction, after all. And it is wonderfully entertaining fiction, with abundant mentions of birds, starring a great detective who is totally cool and a dedicated birder. He doesn’t mention the very large bird book, but I’m sure we could come up with some kind of imaginative explanation why Cordelia has an attachment to it. Personally, and as the mom of a television writer, I understand the necessity of compromise when writing scripts and I’m really glad The Residence producers thought to hire a birding consultant. It’s a huge step forward.

Which brings us to the cinematic and video birder images which has haunted us over the years. Chief amongst them is the “Miss Jane Hathaway Birder,” an image so prevalent Corey cited it in his 10,000 Birds review of The Big Year. For those who did not grow up with a TV show called The Beverley Hillbillies (1962-1971), Miss Jane Hathaway was a gawky, strait-laced bank administrator who was an avid birdwatcher and who occasionally showed up in a khaki birdwatching uniform featuring a neckerchief, badges (did the costume designer confuse bird clubs with the Boy Scouts?), pith helmet, and large binoculars. Her appearance was an immediate signal for the audience to guffaw long and loud; obviously birdwatching was for dorks and spinsters only. Miss Hathaway was played by a very intelligent woman named Nancy Kulp who later ran for political office, but who earlier in her career played another avid, awkward birdwatcher on the 1950’s television comedy “The Bob Cummings Show.” Miss Hathaway’s birdwatching friend was played on one episode by Wally Cox, an actor who defined the term “dork” on early television. But it was Jane Hathaway who people remembered and related to birdwatching.

Screenshot from The Beverly Hillbillies © CBS, 1963

I’m not sure how this stereotype came about, maybe from early birdwatchers’ conscious choice to watch birds through opera-glasses rather than shooting them with guns; maybe from the slightly sentimental aspect of the first bird guides, which were written by women and which emphasized nurturing birds and their habitats; maybe from a more general cultural stereotype that smart women needed to hide their intelligence if they were going to snag a husband. Which brings us to the other predominant stereotype of a birdwatcher in film: the arrogant intellectual. Nowhere is this captured more perfectly than in appropriately, Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963). Mrs. Bundy, an ornithologist, pontificates on bird behavior, declaring stories of angry, attacking birds patently ridiculous. She scolds heroine Melanie Daniels: “Birds have been on this planet, Miss Daniels, since Archaeopteryx; a hundred and forty million years ago. Doesn’t it seem odd that they’d wait all that time to start a – a war against humanity?” There’s actually a lot of truth in what Mrs. Bundy tells Melanie and the diner customers–birds are beautiful creatures and it is humans who make it difficult for them to survive–but her condescension and refusal to take anyone with less academic credentials seriously make her unlikeable and not very helpful, and by the end of the film she is cowering in fright with everyone else.

Scene from The Birds, © Universal Pictures, 1963

A lovely update of Mrs. Bundy and Jane Hathaway is presented in a recent episode of Murdoch Mysteries, a Canadian detective television series set in the early twentieth century. In the episode “Murdoch and the Treasure of Lima” (season 17, episode 15, 2024), author Margaret Atwood (yes, author of The Handmaid’s Tale and an avid birder and conservation supporter in real life) appears as Loren Quinnell, an “amateur ornithologist,” who helps detectives William Murdoch and Llewellyn Watts on a treasure hunting mystery that has taken them to the wilds of northern Ontario. But not before she strictly admonishes them to NOT disturb the migrating Sandhill Cranes in their travels and explains progressive (for 1911) thoughts of Edmund Selous, one of the first ornithologists to advocate for not shooting birds for scientific study. Detective Murdoch, a character known for his interest in science, responds, “Lay down the gun and take up a park of opera glasses,” both a paraphrase of Selous’s writing and a reference to Florence Merriam Bailey’s Birds Through an Opera Glass (1898), one of our earliest and most popular field guides. Quinnell’s clothing style echoes Mrs. Bundy’s severe attire, but she tops it off with a jaunty boater (sans feathers, of course), and a soft, flouncy blouse and neckerchief. She is confident, intelligent, explains rather than pontificates (though she rightly admonishing Detective Murdoch for not doing his job after she trips the fleeing murderer with her tripod), and, like Cordelia Cupp, reads bird books and is never without her notebook (see it on the table below!).

Margaret Atwood in Murdoch Mysteries © CBC Gem, 2024

Portrayals of male birders in media tend to continue the trope of the detail-focused obsessive but are often much kinder than the prickly Miss Jane Hathaway and Mrs. Bundy stereotypes. Pretty much all television procedurals have at least one episode in which birders find evidence (a Raven carrying a human eyeball in CSI is one of my favorites), a body, or witness the murderer doing something incriminating. Birders pop up a lot in British mystery series, especially another of my favorites, Midsomer Murders. In “A Rare Bird” (season 14, episode 8, 2012) the members of the Midsomer-in-the-Marsh Ornithological Society fight over a sighting of a rare Blue-crested Hoopoe (a fictional species that is shown to exist in this fictional world); and in “Sauce for the Goose” (season 8, episode 7, 2005) Ralph Plummer only wants to sit in his bird hide and watch Goshawks, totally uninterested in the family relish factory (unfortunately, Ralph’s bird-obsessed dreaminess makes him complicit in the episode’s murder).

Some of my friends like to bring up a major episode of the series Criminal Minds, when we talk about birders on television. “Nelson’s Sparrow” (season 10, episode 13, 2015) features a serial killer who leaves a Nelson’s Sparrow in the hands of his victims, apparently a reference to the bird’s secretive nature and the way it walks, not flies, from danger. I’m not going to include the character in my list of TV/film birders, though. The killer doesn’t appear to be a birder despite his talent for capturing sparrows (I don’t think they ever explain how he does it) as much as a sick individual whose fantasies were inspired by an aunt who was a birder, a founding member of a bird-watching club called the Flappers (the name as much a figment of the writer’s imagination as the Blue-crested Hoopoe).

At the comedy end of the television spectrum, we have Luke Perry as gentle, obsessive birder Aaron in a 2005 episode of the comedy Will & Grace. Aaron encounters Jack while observing the rare (very rare in NYC!) Golden-cheeked Warbler (unfortunately, while Aaron uses the correct, for 2005, scientific name for the bird, the bird call we hear is reminiscent of Tweety Bird and the bird we see is some kind of dressed-up finch–but that’s fodder for another article). He is wearing stereotypical birder clothes, a khaki vest with multiple pockets, a hoodie and some kind of other layer, a cap, binoculars, and glasses. When asked what the female Golden-cheeked Warbler looks like, Aaron replies, “Who cares?” and Jack immediately concludes that this is “the rarest of all gay subspecies, the hot gay nerd.” But we know that this is simply the normative male bias of birding. Indeed, Aaron turns out to be more interested in money than in birds, leading Jack to call him “the hot, gay opportunist,” but two things can be true at the same time and Aaron remains a fun, modern birder stereotype.

© NBC Universal Television, 2005

These early and not-so-early birders appeared as secondary characters, designed to comment on action or spark humor. It took a big, major studio film, The Big Year (2011), to thrust birders into our cultural consciousness. Based on the nonfiction book The Big Year: A Tale of Man, Nature and Fowl Obsession by Mark Obmascik, the film presents fictionalized versions of the three real-life birders who birded the hell out of 1998: Steve Martin’s Stu Preissler, is a wealthy, kind businessman based on Al Levantin; Jack Black’s Brad Harris is frenetic computer programmer based on birder Greg Miller; and Luke Wilson’s Kenny Bostwick, the outrageous birder holding the Big Year record everyone is trying to break, is based on the late, well-known (some might say infamous) twitcher Sandy Komito. They are all obsessed and the film, like the book, does a great job showing the different ways the obsession is expressed and the limits for each birder. As in real life, it’s the Bostwick character that has attracted the most attention. The character crosses ethical boundaries, plays tricks, sacrifices friendships and relationships to get the bird. He is Obsessive Birder Supreme. Black infuses Harris with comic energy, hopefully setting the foundation for a new type of birder stereotype, the one where birders are having an absolute blast, even when they don’t get the bird. The sanest of the Big Year birders, Martin’s Stu Preissler, the birder who sacrificed his trip to Attu to save the jobs of the people who worked for him, has received the least attention in the media and birder culture, which says a lot about how stereotypes and media images are formed. It’s all about the extremes and the emotions they spark, whether it be awe or laughter or fear.

Perhaps that is why the film that offers the most authentic portrayals of birders (in my opinion) is not very well-known. A Birder’s Guide to Everything (2013), an independent film directed by Rob Meyer, is about the quest of four 15-year old birders to find a Labrador Duck, an extinct bird that David, one of the boys, thinks he has photographed while biking. The three boys are members of their high school bird club, and they are smart, dorky (their club secret language is Latin), obsessed with birds and life lists, but also interested in girls. When Ellen, who has access to a good camera from the school, comes along on the quest, they tease her but also sweetly introduce her to birds and the art of using binoculars.

David has lost his mother, the person who taught him how to bird, and his father is about to marry again. The quest for the extinct duck becomes a coming-of-age story in which he works out his grief and anger, mostly grief. His mentor is an older ornithologist, Lawrence Konrad, who has a history of ill-fated chases–he lost a leg searching for the endangered Pale-headed Brushfinch in Ecuador (he didn’t find it), he lost his driver’s license chasing an albino Nighthawk (a high-speed police chase was involved), and he is sure he saw the Ivory-billed Woodpecker in 2005. As portrayed by Ben Kingsley, Konrad is far from a stereotypical crackpot birder–he is excited enough by David’s blurry photograph to follow the boys to the pond where the duck might be, but sensitive to David’s pain when he learns who his mother is, and treats all the young birders with respect. Even when he tells David, “I’m 63 years old and very much alone. I guide assholes for money. I have one leg and no driver’s license. Please do not confuse me with a role model,” he carries himself with such world-weary dignity that you wonder, how can David not listen to him. (Ken Kaufman was also a consultant for this film, and actually makes a non-speaking, non-birding appearance at the end.)

I see some of Lawrence Konrad’s sense of presence, of gravitas, in Cordelia Cupp. I think it’s a quiet dignity, the confidence, that comes from knowing about birds. I see it in the very best birders I know. Knowing about birds is important because you can key that knowledge into so many other things about life, our own individual lives and life in the widest sense–environmental, societal, even political–and Cordelia uses that knowledge. In the last episode, confronting all the possible suspects, Cordelia goes into a whirlwind of bird and birding history. She cites the Passenger Pigeon and the fact that President Theodore Roosevelt was the last trained observer to see them in the wild to show that the unexpected can happen–in this case, a surprise suspect. The makers of the series go all out for this scene, showing us actual footage of the extinct bird and Teddy in the field. And Cordelia lays out the case for why a great birder is a great detective: “The great birder–and Teddy Roosevelt was a great birder–looks for context, understands relationships, history. What you are seeing needs to make sense. And that flock of pigeons made no sense. They were extinct. But, you also have to trust yourself. Because you know what you are seeing, even if everyone else says no, that’s not it.”

I don’t know what an eBird reviewer would make of this statement, but I love this definition of a birder. It takes us beyond clothes, binoculars, and lists, reaches past the process of identification to a more complex combination of analytic observation and self-belief. And it brings us back to my original question–Is Cordelia Cupp the birder we have been waiting for? Is she how we want the world to view birders? Is she how we view ourselves? For me the answer is a qualified yes. I like birders being considered the smartest people in the room, even if that room includes the president of the United States (any president). I love how unashamed Cordelia is of her birding passion, of wearing and using binoculars in all situations, and how she flaunts her birding knowledge in all situations, even if it doesn’t always make total sense. I would like Cordelia Cupp to be one of several new birder cultural images, and I hope film and television creators will be inspired to give us more. Out with the dork, in with the smartest person in the building!

The Residence was created by Paul William Davies and produced by Shondaland. The first four episodes were directed by Liza Johnson & the last four episodes were directed by Jaffar Mahmood.

The Residence stars Uzo Aduba, Giancarlo Esposito, Molly Griggs, Ken Marino, Randall Park, Susan Kelechi Watson, Jane Curtin, Isiah Whitlock Jr., Bronson Pinchot, Jason Lee, Mary Wiseman, and many other noted actors. It was inspired by the nonfiction book The Residence: Inside the Private World of the White House by Kate Andersen Brower.

Great review, Donna. I’m glad you addressed the issues that frankly took me out of the story like choosing to chase an antpitta in possibly the least sensible way imaginable or using lousy bins at night to look for song sparrows. I’d prefer a portrayal of a birder that makes birders feel seen. That said, I definitely enjoyed The Residence!

An excellent review. As one who spends far more time watching birds than watching television, it actually makes me want to see The Residence. Sadly, I haven’t got Netflix, so I will have to stick with birds.

There’s a cool character played by Christopher Walken as Jamie Shannon, a soldier of fortune who will stage a coup or a revolution for the right price, and prior to the real thing, he does a reconnaissance trip posing as a “rare birds photographer”. More: https://www.10000birds.com/cry-havoc-or-a-birding-movie-before-the-birding-movie.htm

Yes, loved your comment: “any president” 😀

Don’t forget Adam Dagleish in the BBC series based upon PD James’ mysteries.