I recently asked whether Puerto Rico should be part of the American Birding Association’s ABA Area. That post led to a spirited discussion on the ABA Facebook page.

I will suggest an answer to the question: this post makes the argument that both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands should be added to the ABA Area.

# # #

Now that Hawaii is in the ABA Area, the next additions should be Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI). The Hawaii vote made it clear that that the ABA Area is about political borders, not geographical or ecological ones, and the two Caribbean territories have long been part of the United States.

Both Puerto Rico and the USVI have active birding communities that are currently excluded from full membership in the ABA family. And both have fascinating populations of New World birds, from Puerto Rican endemics to Caribbean specialties to Neotropical migrants. The absence of the Caribbean means that ABA Area—and the ABA—excludes important aspects of the avian diversity of the United States.

Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands

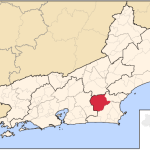

Puerto Rico is a U.S. territory in the West Indies where it is the easternmost and smallest of the Greater Antilles. Puerto Rico became a territory in 1898 and a commonwealth in 1952. It is now an unincorporated organized territory of the United States. The capital is San Juan, an important center of Caribbean culture and transportation. According to the 2010 Census, the population was about 3.7 million, though many have moved to the mainland due to its economic crisis and the impact of Hurricane Maria.

The U.S. Virgin Islands are 40 miles east of Puerto Rico and consist of St. Croix, St. John, St. Thomas, and a number of smaller islands. The islands were purchased by the United States from Denmark in 1916. The population is approximately 105,000 and the capital is Charlotte Amalie on St. Thomas.

Individuals born in both territories are U.S. citizens: they carry U.S. passports, but do not need them to travel to the mainland, just as mainlanders can leave theirs at home when they visit. Both use the U.S. Dollar and the U.S. Postal Service.

Although different territories, they are nearby and share many of the same birds. The USVI are smaller and have fewer habitats and, as a result, fewer bird species. Because it is much larger, this will focus on Puerto Rico.

All Americans Should be Full Members of the ABA Family

In Birding magazine, ABA President Jeff Gordon argued that adding Hawaii would “bring an unjustly excluded community of birders into full membership in the ABA family.” But even with Hawaii, there are many U.S. birders who are still not “full” members of the ABA. In fact, the population of Puerto Rico alone is more than that of twenty states. Indeed, if the goal was to add excluded Americans to the ABA, Puerto Rico should have been added before Hawaii.

Not only are they Americans, there is a vibrant birding and ornithological community in Puerto Rico. The Sociedad Ornitológica Puertorriquea Inc. (SOPI) is the leading ornithological organization and it performs research, education, and outreach. There are three Christmas Bird Counts in Puerto Rico (and three in the USVI), with the first count in Puerto Rico occurring in 1980. There is also a Puerto Rico eBird regional portal. Much of the research regarding Caribbean ecology and ornithology has been conducted in Puerto Rico.

Adding Puerto Rico and the USVI would largely achieve the goal of bringing all Americans into full membership of the ABA family. The only other populated U.S. territories are Guam (pop. 160,000), American Samoa (55,000), and the Northern Mariana Islands (54,000). There are arguments for adding all territories, but experience demonstrates that the ABA moves glacially when it comes to the ABA Area.

The ABA Area should Reflect the Avian Diversity of the United States and Canada

The ABA purports to be the national association of birders for the United States and Canada. The ABA Area includes all of Canada, which has both provinces and territories. For the United States, the 50 states are included, as are Washington D.C. and Midway Atoll, but other territories are excluded. While this might make sense if the territories did not have birds or birders, the Caribbean territories have both.

Puerto Rico has a checklist of 269 species, 207 of which are migratory and the USVI has a checklist of 149 species, 124 of which are migratory. (Herbert Rafaelle includes 284 species in his field guide, which covers both territories.) Both are situated at the convergence of the Greater and Lesser Antilles, and have species from each region. Indeed, Puerto Rico is second only to the much larger Cuba in terms of bird species in the West Indies. Note that the West Indies are generally considered part of North America and are part of the Atlantic flyway.

Many native birds are either endemics or widespread Caribbean species. Some are already on the ABA Checklist: Bananaquit, Gray Kingbird, Red-legged Thrush, Yellow Warbler, White-winged Dove, Scaly-naped Pigeon, and Zenaida Dove. But other species have not been recorded in the ABA Area, including, of course, all 16 Puerto Rican endemics. Some of these are unique examples of U.S. avian diversity: the Puerto Rican Parrot is the only remaining native parrot species and the sole representative of the Tody family (Todidae) is the Puerto Rican Tody.

However, the majority of birds in Puerto Rico and the USVI are “mainland” birds, primarily Neotropical migrants. Numerous warblers winter in the territories, including Northern Parula, Black-and-white Warbler, American Redstart, Ovenbird, Northern Waterthrush, Black-throated Blue Warbler, and others. Many more stop during migration.

Puerto Rico is also important for migrating shorebirds. Cabo Rojo NWR is one of the most important stopover site in the Caribbean. Species include Least, Western, Semipalmated, Stilt, and White-rumped Sandpipers, and Lesser Yellowlegs.

Simply put, the current ABA Area does not reflect the true diversity of the birds of the United States, a manifest shortcoming for a national birding association.

The ABA Area Should Reflect Bird Conservation in the United States

Although the ABA Area generally follows political borders, is inconsistent with how the federal government treats both Puerto Rico and the USVI when it comes managing and preserving birds and administering federal public lands. While there is obviously no requirement that the ABA align itself with the federal government, not doing so results in some oddities.

For example, the Endangered Species Act and Migratory Bird Treaty Act—America’s most important avian conservation laws—apply in both territories. Both territories are also part of the U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan and other avian conservation plans.

The current ABA Area also excludes parts of our iconic systems of federal lands, including the National Park System (e.g., Virgin Islands NP), the National Wildlife Refuge System (e.g., Culebra, Laguna Cartagena, and Vieques NWRs), and the National Forest System (e.g., El Yunque NF). These are the most important systems of lands for birds and bird conservation in the United States. Some are unique: El Yunque is the only tropical rain forest in the National Forest System.

Thus, one can currently go birding in Virgin Islands National Park yet be outside the ABA Area, but be inside when birding under the French Tricolour in St. Pierre et Miquelon. And one can go birding on federal lands (e.g., Cabo Rojo NWR) and see ESA-listed endemic birds (e.g., Yellow-shouldered Blackbird), but not be in the ABA Area. This makes no sense at all for a group that purports to be the national birding organization for the United States.

Expanding the ABA Area would Promote Avian Conservation in the Caribbean

Like Hawaii, the conservation argument is compelling: the Caribbean is one of the world’s most threatened biodiversity hotspots. Puerto Rico and the USVI exemplify many of the conservation issues in the region. Both were largely deforested for agriculture and urbanization has further reduced the available habitats for birds. Moreover, invasive species have impacted much of what remains. Obviously, hurricanes pose a threat to some species.

Puerto Rico has a number of endangered birds, several of them endemics, including Elfin-woods Warbler, Puerto Rican Parrot, Yellow-shouldered Blackbird, and Puerto Rican Nightjar, as well as the Puerto Rican subspecies of Sharp-shinned Hawk, Broad-winged Hawk, and Plain Pigeon. The Puerto Rican Vireo is declining.

Although most conservation research focuses on northern breeding grounds, many ABA Area birds spend most of the year elsewhere. Despite their significance, migration and wintering grounds are under-researched, though there are some exceptions.

The Guánica Avian Monitoring Project, led by Drs. John Faaborg and Wayne Arendt has been tracking bird populations in the Guánica Commonwealth Forest since 1972. Guánica has large now-rare tracts of high-quality subtropical dry forest and has historically supported a large and diverse population of wintering birds. But recent trends are disturbing: after years of stability, the wintering bird community declined dramatically after 2001. Although the declines are clear, the causes are not. Research is ongoing.

Similarly, recent analysis of migrating and wintering shorebirds have shown precipitous declines. Studies at Cabo Rojo NWR have shown that virtually all species have declined more than 70% between 1985 and 2015.

Puerto Rico has been at the forefront of ecological research in the Caribbean, in large part because of the U.S. Forest Service (particularly the International Institute of Tropical Forestry) the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. Studies include the ecology of wintering warblers, and the impact of hurricanes and urbanization on birds. The Puerto Rican Parrot and its captive-breeding program has been extensively studied, as has the Pearly-eyed Thrasher, among others. Much of the research has been applied throughout the Caribbean and beyond, but there is much to be done.

Adding Puerto Rico is Consistent with the ABA’s Commitment to Diversity

Birding has a well-known diversity problem, namely that it is overwhelmingly a pastime of affluent, educated, middle-aged whites. Even a cursory analysis of any birding festival indicates that minorities are the rarities. A FWS survey found that “Ninety-three percent of birders identified themselves as white.”

The ABA and other birding organizations consider diversity important and have attempted outreach to minorities. For example, the ABA has sponsored conferences and its publications and blog have addressed diversity. But progress is slow.

Most Americans now live within the ABA Area, but by far the largest excluded group is the Puerto Ricans and the overwhelming majority of them are Hispanic. Thus, despite the absence of any malicious intent, the Americans excluded by ABA Area are virtually all Hispanic. This is akin what lawyers call an “adverse impact,” namely neutral line drawing (here, states but not territories in the ABA Area) that has a disproportionate impact on a group (here, Hispanics).

This is a problem and it should be corrected. In addition to other benefits, expanding the ABA Area into the Caribbean would be a step towards diversifying the ABA.

The Arguments Against are Unpersuasive

Currently, there is no organizing principle for the ABA Area. As ABA President Jeff Gordon has stated, the “ABA Area is more a political, cultural, and recreational construct.” It seems to be a combination of geography, ecology, political boundaries, and tradition, selectively and inconsistently applied. Depending on the area desired by the advocate, these factors are weighed differently or not at all. However, the Hawaii vote makes it clear that neither geography nor ecology are the driving forces to the majority of ABA members.

But even if they were, unlike Hawaii, both territories are part of North America and their native birds are New World species, most already on the ABA Checklist. Sometimes it can literally be the same bird: a Black-and-white Warbler that winters in Guánica likely breeds in or around Pennsylvania. The birds not already on the ABA Checklist are generally related to ABA Area birds. For example, the two endemic warblers (Elfin-woods Warbler and Adeliade’s Warbler) are both in the genus Setophaga, just like most other North American Warblers.

Although there has been little substantive discussion about adding Puerto Rico and the USVI to the ABA Area, a few arguments have been either suggested or implied.

Not a State: The most common objection appears to be that territories are not states. But Washington D.C. is not a state, and neither is Midway Atoll, but both are in the ABA Area. Thus, statehood cannot be a requirement.

Moreover, it is not clear why statehood should matter to a national birding organization. The U.S. Government makes no distinction when it comes to birds or bird conservation or federal public lands. As indicated above, ESA applies and there are units of the National Park System, National Wildlife Refuge System, and National Forest System in the Caribbean territories. But most significantly, the residents are U.S. citizens. There is no credible reason why statehood should matter, particularly when other non-state areas are already part of the ABA Area, as are Canadian territories.

This is sensible: why should political subdivisions within a nation apply to a national birding organization?

Travel: To the extent travel is relevant, going from the mainland to Puerto Rico is easy, though the impact of Hurricane Maria has caused a significant short-term challenge. Indeed, from most major U.S. cities it is more convenient than Alaska or Hawaii or many smaller cities in the lower 48. There are many direct flights served by several major airlines. The flight from Atlanta (the busiest airport in the U.S.) to Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport in San Juan (the busiest airport in Puerto Rico) is about 1,550 miles. For comparison: Atlanta to Denver is 1,200 miles, Atlanta to San Francisco is 2,100 miles, and Atlanta to Honolulu is 4,500 miles. The USVI are almost as easy: Cyril E. King Airport on St. Thomas is accessible from several mainland airports on flights by major airlines. Both San Juan and St. Thomas are also among the most popular ports of call for Caribbean cruise ships that depart from the mainland.

Changing the Rules: There are some who believe that the ABA Area should not have changed for Hawaii and certainly shouldn’t change again. But there is nothing sacred about the current area, which lacks a meaningful organizing principle. Moreover, listing rules effectively change all the time, from what species can be counted, to taxonomic changes, to changes in areas that can be accessed, to say nothing of the rise of technology and the near-instantaneous distribution of information about rarities. In any event, membership rejected this argument when it added Hawaii and there are now multiple listing areas available to ABA members.

Of course, many arguments for Hawaii also apply to the Caribbean territories. There are interesting birds, including endemics and Caribbean specialty species. Expansion might focus needed attention on Puerto Rican birds (several imperiled) and countless migrants, many in steep decline. Both territories have been overlooked by birders despite being part of the United States. Both have splendid year-round weather, tropical beaches, and diversions for non-birding significant others, an unusual and valued birding attribute. They are also fine birding locations: the ABA held a birding rally in Puerto Rico in October 2016. Both the forests and the birds will survive hurricanes Irma and Maria: they have evolved with hurricanes and are resilient.

Conclusion

Adding Puerto Rico and the USVI to the ABA Area would open an entire region—the Caribbean—to increased interest by ABA birders. It would grant an unjustly excluded community of birders “full” membership in the ABA family and would encompass more of the full avian diversity of the United States. It would also make the ABA Checklist the de facto checklist for all of the United States (and Canada), not just most select parts of the United States. It would be a step toward greater diversity in the ABA.

At the end of the day, the ABA Area is simply a geographic area within which the ABA “counts” certain birds for one of the lists it recognizes. But anyone can keep a list of any area (e.g., World, ABA Area, Canada, Idaho, San Mateo County, a backyard, etc.) and Birding magazine will print achievements for just about any list in its “Milestones” section. Given the declining significance of any particular list, it makes sense to cover as many American and Canadian birders as possible and let people select whatever list (or no list) they like. Any changes regarding conservation or interest by birders are likely to be modest, but including all Americans seems like a worthy goal.

While there is no “correct” ABA Area and no single area that will satisfy everyone, it is worth considering an ABA Area that consists of all of the U.S. and Canada including all provinces, states, districts, and territories. It is the fairest, most inclusive, and simplest option that could be adopted, and it is consistent with the addition of Hawaii. It would also have a guiding principle and would bring essentially all Americans and Canadians—and the full avian diversity of both countries—within its ambit.

Photos (from top to bottom): Trunk Bay, St. John, USVI; Bananaquit; Black-faced Grassquit; El Yunque NF; White-cheeked Pintail, Bridled Quail-dove; by Jason Crotty.

The related discussion on the ABA’s Facebook page:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/ABAbirds/permalink/10156258404895715/