Larry Chen is an obsessive but frequently-distracted birder who has recently taken up spending far too much time looking for plants, insects, fish, and other decidedly unfeathered taxa on top of birds. He is frequently puzzled at the notion of a slow and relaxing international vacation as his trips abroad invariably involve some mixture of 4 AM wakeups, remote forest preserves with copious leeches, and extensive spreadsheets covered with subspecies names and map coordinates. Larry is decidedly unskilled at photography, and hopes that pretty landscape photos, friends open-handed in ‘lending’ their bird images, and questionable humor will carry him through the blogging world.

How did you get into writing the eBird species entries?

It was part of my first on-campus job when I started my undergraduate program! During my freshman fall at Cornell, I met with some folks at the Lab of Ornithology, and they were kind enough to offer me a position (a fair number of bird- and nature-interested undergraduates are generally working at the Lab at any given time, as far as I know). I worked with the Macaulay Library on the Merlin Bird ID app, and they were still pushing to have Merlin coverage for all the world’s species at the time, and my account-writing back then was part of that push.

When writing an entry, how do you prepare, particularly if it is a species you have not seen yourself?

I started off writing about species in eastern China, most of which I had seen—species with which your readers would be familiar with from your Shanghai posts, such as Blue-and-white Flycatcher, Red-billed Starling, and Falcated Duck. Even for those species, though, I didn’t want to rely solely on my personal knowledge. I checked a range of references, including (but not limited to) field guides and what was then the Handbook of the Birds of the World Online (now Birds of the World). I also looked through photo and audio files in the Macaulay Library, and videos as well—though these were often a bit on the sparse side in Asia, it was great to see various bird behaviors that couldn’t be as well-captured in a photo, especially for species I’ve only seen briefly (or not at all) in life.

How many entries did you roughly write?

To be fully honest, I lost track quite early on, as I did the accounts in batches, and I did several batches, all with different numbers of accounts each. I think the final count was somewhere between 2000 and 3000.

How does writing these entries relate to your career or studies – do you study ornithology? If yes, what are your plans after you have finished studying?

You’re definitely not the first person to ask if I study ornithology! A lot of folks are rather disappointed–or at least surprised–to hear that Cornell doesn’t technically have an ornithology program—the Lab of Ornithology is part of the university, but there isn’t a formal major for the subject there (at least not when I was there—there was always some informal talk of developing one, but I have no idea if any of that’s come to pass). I majored in Environment & Sustainability, and a lot of my other birder friends majored in Biology. Writing these entries has been fun, and could potentially be construed as being “technical writing” of sorts, but they probably won’t end up relating to my career too much, ultimately. I actually just finished a Master of Public Policy program at Duke University, and am looking at a range of different employers, none of which, thus far, have been particularly tied to ornithology or birding.

What other birding or ornithology-related activities have you done?

I’ve birded a fair bit, and have had the privilege to bird internationally over the past few years! I was not the most serious or intense birder while living in China, which I deeply regret, and I tried to make up for it during winter and summer breaks when visiting my family back in Shanghai. Even still, I’m missing quite a few really very readily gettable species in China, with some of the common rural species around Beijing being some of the worst offenders (quite a few of my Beijing-based birding friends have all but spewed blood when I told them that I’ve still not seen a Pere David’s Laughingthrush or Beijing Hill Babbler). Here in the United States, I’ve seen a good majority of the expected species outside of a handful in the Aleutian Islands, some of the scarcer pelagic species off the west coast, and the native and non-native species on the Hawaiian Islands. Nowadays, I mostly spend my free time in the US looking for new species among other groups—plants, fish, invertebrates, that sort of thing—and post them onto iNaturalist, which is a really fantastic biodiversity community science site.

As for ornithology proper, I’ve never done formal research, unfortunately. A good number of my friends have (and are!) though, and it’s always a phenomenal time getting to hear about their stories, whether from the field, in the lab, or just dealing with the various characters in that realm. I have always counted myself fortunate to be surrounded by capable, accomplished peers who have done—and I am certain will do—incredible work in the biological field.

I am somewhat puzzled by the connection between Merlin, eBird, and the HBW Online. My understanding is that both are operated by Cornell University, and they seem to share many elements, but sometimes have diverging descriptions. Can you explain?

I’m a little hazy on the precise details of this situation, but Merlin and eBird have always been a part of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, as far as I’m aware. The written species accounts on Merlin are the same as on eBird—my old coworkers may be a little more positively inclined for them to be called “Merlin accounts” (vs “eBird accounts”), as Merlin is where they first appeared, but functionally, both terms refer to the same thing. HBW Online (HBW being short for “Handbook of the Birds of the World”) was originally its own independent site, which compiled information on all the world’s bird species—or, rather, all the species that it recognizes, which is where things sort of get a bit fuzzy. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology (back in the early 2020s, I believe) purchased HBW Online and subsumed that site’s information into its own compiled archives. Back before this point, the Cornell Lab had a site called the Birds of North America (or something along those lines), which had detailed species accounts for all North American bird species—the purchase of HBW Online set up the creation of analogous accounts for all of the world’s bird species, at least those recognized by the Clements checklist, which is the taxonomic authority the Lab of Ornithology uses.

Much of the HBW site’s original information was then copied over to a new “Birds of North America” type format, which is what became “Birds of the World Online”—now a resource under the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s banner. However, because the old HBW Online used a different taxonomic authority than the Lab’s Clements list, the taxonomic details are often a bit out of sync—Birds of the World Online accounts that have minimal information because they were transferred over from a taxon that was only recognized as a subspecies by HBW, and so forth. The BOTW team is working hard on these issues, but it’s a sizeable task and is still in progress, at least as far as I know.

Of course, I am also curious about whether you have any favorite birds or bird families…

My favorite bird back when I was a kid, first getting into birding, was the Common Kingfisher! I haven’t had any reason to bump it out since then, so it remains my favorite by default. Quite a common bird in Shanghai (and, of course, throughout much of northern Eurasia), and I’ve actually had the privilege of seeing the Moluccan “Cobalt-eared” subspecies as well as the ones in mainland East Asia—quite a striking and different-looking little bird compared to their more widespread cousins.

As for a family, I’m not sure! There are plenty of bird families I like, but none that I’d say are unequivocally a favorite. Charadriidae, the plovers and lapwings, are up there for me, as are the Australian family Maluridae, which Birds of the World refers to as the “fairywrens”, but which also includes emuwrens and grasswrens. All are charming, rather stout-bodied little birds with long, slender tails and some really striking patterns. The parrotbills of Paradoxornithidae are also up there (a predominantly Asian family, many members of which have adorable round heads and tiny bills), as are Sittidae, the nuthatches. The monotypic Wallcreeper (family Tichodromidae) is also one of my favorites—this crazy little long-billed bird, which crawls around on cliffs and other vertical rocky surfaces (my lifer was on the crumbling defensive walls of an old fortress in Tibet), and which fans and flashes its brilliant red-and-black wings like a butterfly. I could go on and on about these, but either way, I’m afraid I don’t have a straight answer for your question here …

…and any favorite birding destinations?

Oh man, there are too many good ones here too…I’m going to assume that you’re asking if there are places I’ve been to that are favorites, since there are definitely too many I’d like to go to. One would be the rural village of Malagufuk in western Papua, on the Vogelkop (Bird’s Head) Peninsula. It’s deep inside the forest, and the folks, in opening up their community to ecotourism, built this long, slippery boardwalk connecting it to the main road. The birding there is incredible, and really felt extraordinarily easy (before going to Papua, I was finding several accounts describing how difficult birding on the island was), with birds just about everywhere, including some species that can be fairly difficult to see elsewhere—the Tawny Straightbill is one, and the Red-breasted Paradise-Kingfisher is another. Folks have also had New Guinea Eagle there, as well as Doria’s Goshawk, Forest Bittern … the list goes on and on. I had some incredible insects and amphibians there as well, and every morning (after waking up to the song of the Twelve-wired Bird-of-Paradise) we’d find the tracks of the Western Long-beaked Echidna … never did see one of those though, yet another reason to go back!

Another favorite was what the Nanhui wetlands in eastern Shanghai used to be—I would guess that readers on your blog are familiar with that name? The habitat’s mostly been trashed now, but back when I first started birding in Shanghai as a kid (early to mid 2010s), that area was just full of expansive reedbeds, shallow ponds, and roadside “islands” of shrubby trees that were thronged with migrants in spring and fall—now, only the little roadside “islands” remain, though the mudflats do still get some good shorebirds and waterbirds. It was crazy good back then though–novice birder that I was, I could still see more than 100 species pretty readily in a given morning, which is pretty wild given that I was (1) not very skilled back then and (2) did not start identifying birds by vocalization until I arrived at Cornell around 2017/2018.

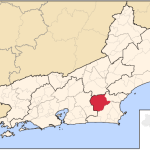

I could go on and on here, as well—so many cool places out there! Two of my most recent favorites were Itatiaia National Park, in southeastern Brazil, and Wawushan in central China, but I’ve already spent too much time on this question … maybe another post …

Finally, as you have birded extensively in both the US and China, what do you think are the main differences related to birding and birders?

This is a tough one, as I’ve felt both inside and outside with regards to these communities, but I’ll give it a stab …

I think that one of the main points of difference is that there are more folks who would consider themselves birders or birdwatchers per capita in the US than in China. I don’t have numbers for each, and the birding community in China is growing at an incredible pace, but birding overall seems more widespread and popular in the US. The US birding community is also very well-established, with oodles of national- and regional-level field guides, listservs, group chats, etc. The Chinese birding community also has plenty of different groups of varying sizes, but there are fewer field guides overall, and things often feel a bit ‘newer’ overall.

Another key distinction (and this is the one that a lot of my birding friends who’ve transferred from Asia to North America for academia will often note) is the level of coverage throughout the two countries. While there are very much regions in the United States that receive less attention comparatively when it comes to birding and ornithological surveys, there is so much of China that receives way less. To a lot of folks who move from China (as well as other Asian countries) to North America for birding, the birding stateside feels quite ‘boring’ in that they don’t get the same sense of discovery and novelty when it comes to the possibility of, say, finding a new regional record, a new breeding range extension for a particular species, that sort of thing. Something I’ve definitely heard (and been guilty of repeating myself at times) is that you can find what feels like a rare bird here in the US, but upon looking at eBird, find that it’s already the 7th record for a hotspot with a name like “Cherry Grove County Park–Duck Pond.” In terms of coverage and understanding the status and distribution of birds in North America, this is very much not a bad thing—but to someone who’s coming from a different birding background, it can definitely feel a bit disappointing and discouraging.

Another point of difference is that the bird community in China often feels more photographer-heavy—and I say ‘bird community’ here and not ‘birding community’ because the bird photography scene in China is, on average, quite distinct from birding, at least that I’ve seen. There’s also definitely a sizeable bird photography in the US as well, but they often feel like they grade more smoothly into birding, though this is definitely not a monolithic thing. Bird-baiting (the use of food to lure birds into view, sometimes onto these artificial mossy-carved-wood setups) for photography purposes is definitely more prevalent in China; in the US, bird feeders are abundant (and not just limited to dedicated birders), but are generally not for dedicated photography use. Bird feeders in the sense they’re used in the US are very rare in China.

Given your knowledge and background, would you be interested in writing for 10,000 Birds?

I’d love to!

Larry is decidedly unskilled at photography, and hopes that pretty landscape photos, friends open-handed in ‘lending’ their bird images, and questionable humor will carry him through the blogging world. ARE WE RELATED???

This was a great interview. I was surprised that China is more photography-heavy than the US. I don’t know why this surprises me – perhaps because in the US it seems that birding and photography are practically synonymous. I guess I do occasionally see a birder without a camera – but if feels very infrequent. A lot of birders in the US practice their smartphone w/ spotting scope skills. Also, I was looking for the discussion of “leeches.”. Did I miss it? I recently spoke with a birder who had returned from visiting a leech infested area – Borneo maybe. Even her stories were eye-opening.

From my experience, in China, many older people are just bird photographers but not birders at all. They come to a hide or a location and ask questions like “Where is the beautiful bird” or “Are there any big birds here”? Not sure whether this could happen in the US – I assume there a basic interest in and knowledge of birds could be expected.