Like most North American birders, I never pay much mind to the European (Common) Starling (Sturnus vulgaris). Sure, they’re always a dependable, can’t-miss tick whenever you need them to be there, whether it’s the first day of the year, or the first few minutes of a Big Day or Christmas Bird Count. And, if you care to admit it, they do look rather attractive in their own sweet way, with their bright yellow beaks and their shimmering, purplish iridescence.

A Starling (undated) by English painter Isaac Spackman (died 1771).

But there’s no getting around the fact that the starling is likely the most detested bird on the continent – as far as birders are concerned, anyway. Learning the truth about starlings is one of the earliest rites of passage for any North American birder. The moment some naïve recruit spots one on a club field trip and expresses the slightest admiration for this handsome songbird with its otherworldly vocabulary of mechanical whistles and squeals, a chorus of more experienced birders can be counted on to chime in to “correct” this misplaced enthusiasm. Starlings, they’ll dutifully explain, are ruthless invasives that have been responsible for the serious declines of several beloved native species, like the Red-headed Woodpecker (Melanerpes erythrocephalus) and the Eastern Bluebird (Sialia sialis). And there’s a good chance that, while they’re at it, they’ll trot out that dubious bit of trivia about the starling being brought to America as a part of some scheme to introduce all the birds mentioned in the works of William Shakespeare to New York City’s Central Park.

So, I too was trained to ignore starlings early on, counting them when I have to, but for the most part, overlooking them in favor of our native avifauna. But I have to admit I’ve been giving a little more attention to them this year than I have in the past. Beginning this year, New York State embarked on its third-ever breeding bird atlas, and it’s the first one I’ve been able to participate in as a birder. And, whether I like it or not, the much-reviled starling turned out to be one of the very first species for which I could confirm breeding in this citizen-science endeavor — and for that, I had to give them a bit more attention than usual.

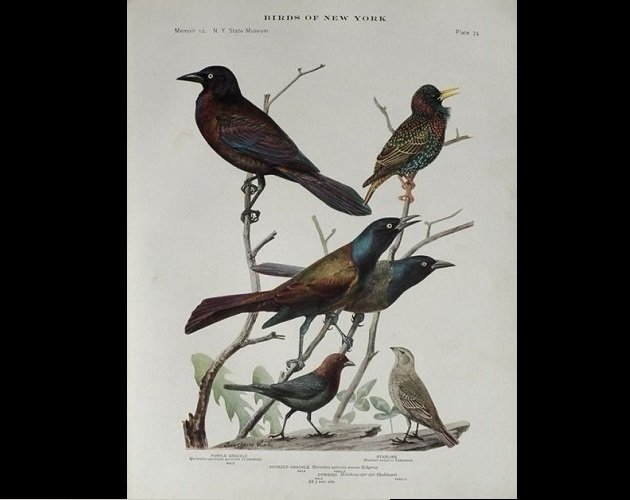

American ornithologist and artist Louis Agassiz Fuertes (1874-1927) chose to depict the European Starlings with native birds of the family Icteridae — birds it commonly associates with — in his two-volume Birds of New York, commissioned by the New York State Museum in 1904.

European Starlings are fond of farms and human activity in general, so it came as no surprise that I was able to find evidence of them breeding so easily at Normanskill Farm, a working farm in Albany, New York that’s become my favorite local patch. Over the last several weeks there, I’ve watched them gather bits of straw and other sundry materials and ferry these back to their nest holes in the old barn walls and eaves. It wasn’t long before their efforts paid off and begging starling fledglings began making an appearance outside the nest, strutting awkwardly around the barnyard and screeching for food.

A starling with nesting material at Normanskill Farm in Albany, New York, in May.

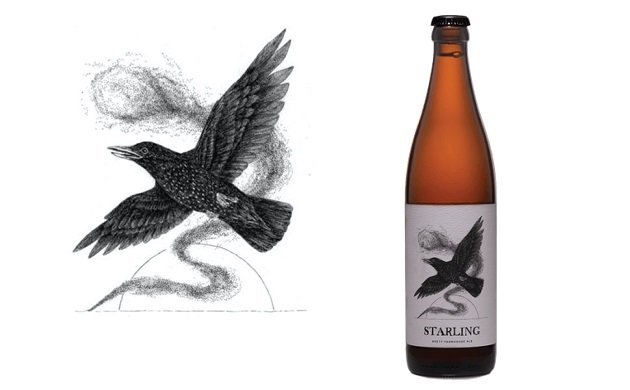

There must be starlings nesting at Arrowood Farm Brewery too, a Hudson Valley hop farm about sixty miles south of me and the brewery behind this week’s beer, a farmhouse-style ale named Starling. While Arrowood might lose some birder cred for that species selection, at least the brewery had the good sense to decorate the undeniably attractive label with a swarming murmuration of starlings – one of those spectacularly twisting and swooping flocks that’s usually the only behavior for which even the grumpiest of birders will admit the slightest bit of appreciation for the nonnative Sturnus vulgaris.

While I don’t think it was an intentional analogy, the signature flavors in Starling (the beer) are contributed by wild yeast of the genus Brettanomyces, undomesticated strains that are generally as unwelcome in most brewing and winemaking operations as the European Starling is outside of its original range. But some brewers have embraced the presence of Brettanomyces in their brewhouses, mostly notably in the making of a handful of archaic Belgian styles that were long little appreciated outside of that country. Lately, however, once the rest of the world finally caught on to the pleasures of Belgian brewing, brewers from far outside the Low Countries began experimenting – with some caution, perhaps – with the sometimes unpredictable but often unique flavors made possible with by letting loose this wild yeast in a carefully-crafted beer.

One such Belgian original that owes its characteristic flavor to Brettanomyces yeast is the iconic ale Orval, brewed by Trappist monks at Abbaye Notre-Dame d’Orval, near the French border. Arrowood’s Starling Farmhouse Ale appears modeled on this classic and it even rivals the original in its complexity. It’s brewed with New York barley and wheat, producing a straw-colored, pale golden beer with a soft, foamy head. In brewing marketing, the label “farmhouse” beer can mean lots of things (though – it’s worth pointing out – it almost never means that a beer was literally made in such a building), but it usually indicates that the drinker should expect some rustic funkiness from the beer, such as the flavors produced by various strains of wild yeast. Starling has these features in spades, with heaps of earthy, musty aromas redolent of leather and woodsy, white pepper, all woven together with an impressive palette that recalls pineapple, orange soda, candied ginger spice, and warm banana bread. The fruitiness takes a less tropical turn with the first sip, with white grapes, green pears, and a touch of clove offset by some smooth bitterness and a slightly prickly tartness. Starling’s finish is dry and crisp, but supple, with an herbal hint of lemongrass at the end.

Starling may not be named for everyone’s favorite bird, but it’s a fine, intricate beer that’s perfectly enjoyable now, and may even get better with a few years stored away in the cellar. And it just goes to show that it’s alright to show a little appreciation for an unwanted species once in a while, whether it’s yeast or bird.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Arrowood Farm Brewery: Starling Brett Farmhouse Ale

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Five out of five stars (Outstanding).

Leave a Comment