Whoever coined the term wake for a gathering of feeding vultures clearly had a sense of humour, but had not, I expect, ever witnessed such an event at close quarters. I did just that in the Spanish Pyrenees last week: it was a memorable experience that I’m unlikely to forget. The fact that as many as 300 vultures came to the wake made it visually spectacular, but it was their behaviour that was so entertaining.

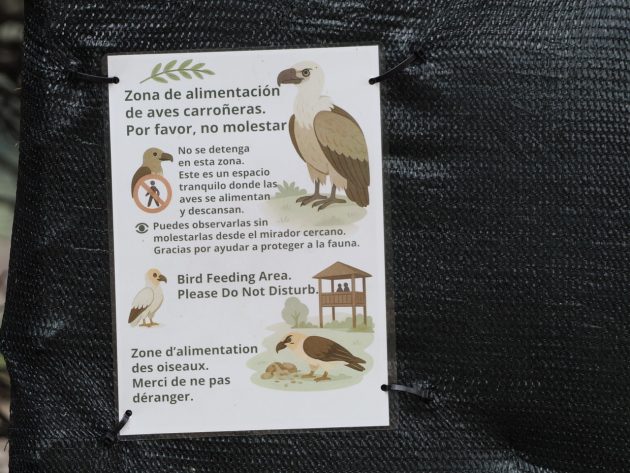

Vulture restaurant – do not disturb

The Land-Rover Defender bringing the vulture’s breakfast

The view from the hide. The first vultures are already arriving before their breakfast has been unloaded

First of all, I will set the scene. The wake I attended was just outside the attractive Pyrenean village of Aínsa, a medieval settlement on the banks of the tumbling Rio Cinca. (Look for Dippers and Kingfishers – I found both). Surrounded by impressive massifs, it’s 869m above sea level (almost 3,000ft) and is in the heart of vulture country. Spain supports more Griffon Vultures than any other country in the world, and these huge birds are at their greatest density here in the province of Aragón. Look to the sky when you are in Aínsa and it’s difficult not to see a soaring vulture.

Griffons are among the largest of Europe’s birds

Griffon Vultures are big birds that need a lot to eat, so all over Spain there are now vulture restaurants, where fallen livestock or waste from the local abattoir is put out for the them. As a result Spain’s population of Griffon Vultures is higher than it has ever been. In the past these birds were heavily persecuted; many were shot, while great numbers died from poisoning, often by eating meat laced with strychnine put out to kill wolves or foxes. Today vultures are not only protected, but the local people have come to appreciate the valuable role they perform. An information board at the Aínsa vulture restaurant informs readers as to how much more environmentally friendly disposing of waste meat with vultures is, compared with incineration or other methods.

Griffon Vultures can be aged by the colour of the iris. This is a young bird (under five years of age) with a hazel-coloured iris

But back to the story of the wake I attended. My companions and I arrived at the restaurant at 9am, breakfast-time for the vultures that had already gathered on the nearby hillside. We followed a brand-new Land Rover Defender (lent to the project by the company JLR), into the restaurant, taking our seats in the two hides overlooking the feeding area, a grisly patch of ground covered in horns and bones – the inedible bits of dead animals. By the time we had taken our seats the action had already started. Despite the fact that the contents of the Defender’s trailer (an unappetising mixture of cow stomachs and bits of sheep) were still being unloaded the first vultures were already pouring in, with squadrons more following behind.

A fresh-plumaged adult Griffon, with bright white ruff and trousers

At least 200, possibly as many as 300, Griffons were now just a few feet in front of us, feeding as fast as they could. There were brief fights, numerous squabbles and a lot of hissing and screeching as they gobbled up their breakfast. I’ve been to a number of wakes, but never one quite like this. It was much noisier than I expected, and a lot more violent. The fights were clearly quite ritualised, with the aggressor pecking, barging or even knocking over its rival, using both feet and beak, with wings raised, neck outstretched. These encounters looked to be serious, but they were are all over in seconds, with no obvious damage other than a few flying feathers. You barely had time to point your camera at the squabbling birds before order was restored.

Fights and disputes are usually over quickly

After all the griffons had arrived a single adult Egyptian Vulture joined them, looking surprisingly small and smart. A bit like a scrum-half in a rugby match, it dodged confidently among its bigger cousins to pick up the scraps. It didn’t stay long, but a few minutes later another came, or was it the same bird returning?

An Egyptian vulture joins the fray

Unlike the largely resident Griffons, Egyptians Vultures are summer visitors to the Pyrenees

Before long birds that had eaten sufficient had hopped away to the edges of the restaurant, sitting around happily with a full crop. Others continued feeding, but it was not long before all the easy meat had been consumed, and soon all but a few of the vultures were just sitting quietly. They did so for some time, with only the odd bird flapping off, but then there was sudden mass departure, with only a single bird remaining. Most flew to the scree slope on the nearest mountain, where they just sat and waited, anticipating the second course which arrived an hour later. We then enjoyed a repeat of the action.

A Griffon departs

This time the birds hung around for much longer, giving the chance to compare plumages, The oldest birds were the palest with the whitest ruffs, the juveniles darker and plainer. One fresh-plumaged adult was late to join the party: he was a very smart bird with immaculate white trousers and ruff. Close inspection of the assembled company revealed a wide range of ages. The old birds have an iris that is a pale yellow-brown, while with the younger birds (up to five years) it’s hazel-coloured. The older birds also display much paler plumage than the youngsters.

Old Griffons become increasing pale, as can be seen with this bird on the left

By now it was becoming hot and stuffy in the hide. The vultures were no longer proving any action for photography, so there was a chance to look at the other birds at the site. Two cock redstarts were flitting about continuously, while other birds to put in an appearance were Pied and a single Spotted Flycatcher, a juvenile Whitethroat, a Tree Pipit, a pair of Serins and a crowd of House Sparrows. A Blackbird and a Robin also appeared briefly. Fly-overs included a single Red Kite, a pair of Ravens and a pair of Carrion Crows.

A passing Raven

A cock Common Redstart prospecting among the bones

It’s not just vultures: this migrant Tree Pipit was also photographed from the hide

This particular restaurant was, we were told, popular with Lammergeiers or Bearded Vultures, and we were were hoping that individuals would come in. The Spanish name for this bird is Quebrantahuesos, which translates as bone breaker, for bones form the major part of this vulture’s diet. They tend to arrive after the Griffons, as they are interested in the bones rather than the meat. Frustratingly, none came in, though a single individual flew over just as we left the hides at 2pm.

Later in the afternoon we visited the Eco Museo de la Fauna Pirineaica, housed in Aínsa’s old castle, where we had the chance to learn more about the raptors of the Pyrenees, and the importance of the Quebrantahuesos to the ecology of the area. The presentation we were given was outstanding, and much recommended. It was here that I managed to photograph a whole flock of Bearded Vultures (see below), though these weren’t the pictures I was hoping for.

The hides my photographs were taken from are owned and managed by The Fundación para la Conservación del Quebrantahuesos, a charity which has done much to restore the Bearded Vulture in the Pyrenees. Birding tourism is much encouraged in Aragón, with dedicated lodges and experienced guides throughout the province. For more details look at https://birdingaragon.com/en/birding-aragon/. The website includes details of the birds you can see, the best routes to take, as well as such essentials as to where to stay.

Next week David describes a day in Ordesa National Park in the high Pyrenees.

Fantastic photos and I can imagine the riveting experience. Thanks for sharing both and I am looking forward to the next.

A good wake is a celebration of life and should be a tad rowdy. I’m more flummoxed by the name for a group of flying vultures: a kettle?

But such a great story again, David, thanks

That last picture was priceless! Thanks for a great read.

I haven’t been to Europe for about 5 years and do not miss it much, but this post makes me think again.