Would you know a Firewood Gatherer if it landed in front of your binoculars? Or, come to that, a Greater Thornbird or a Buff-bellied Flowerpecker? To be honest, I wouldn’t be too confident of identifying any of this trio, either, though all three feature on my world lifelist.

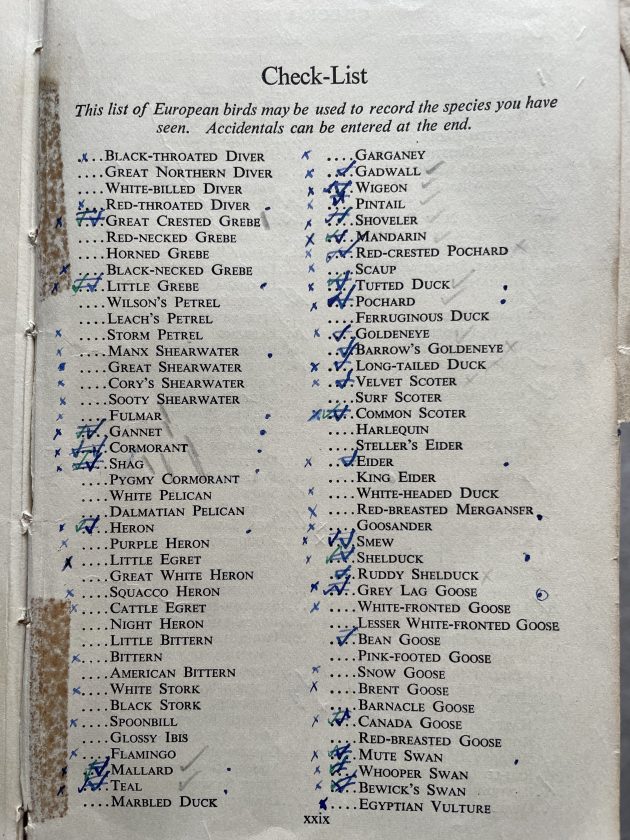

My first-ever check list, in A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. I can no longer remember what my complicated system of ticks and crosses means

Like most of us who watch birds, I enjoy listing. It all started many years ago, when for my ninth birthday I received my first copy of Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. In the front was the first checklist I’d ever seen: it featured all the birds of Europe, and within days I was ticking away merrily. There weren’t too many ticks to begin with, but the list got its first major boost that summer when I spent three weeks camping in Europe with my parents. I can remember puzzling hard over the buzzard plate. Had I seen a Honey Buzzard, or was it just a Common Buzzard? The distribution map showed that both birds were a possibility, but Peterson’s illustration didn’t make it easy to tell them apart, as their shape was virtually identical, and their markings didn’t seem that different, either.

The illustrations in the original A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe didn’t help separating Common Buzzards (above) from Honey Buzzards (below)

In September 1971 my birding career came to its first (and last) major crossroads. Should I go for my birdwatching holiday to the Scillies, the islands off the west cost of England famed for attracting rare migrants, or to Greece? Greece won, as I was much keener to build my European list rather than add a few rarities to my non-existent British list. As a result I’ve never bothered with a British list and have never done much in the way of twitching. I did twitch a Glossy Ibis in North Kent in 1972, but I found it a curiously unsatisfying experience.

Twitching my first-ever Glossy Ibis in Kent was curiously unsatisfactory: seeing the same species in Greece was much more exciting. Today this species is a regular migrant to Britain

I ticked my first Hoopoe in Spain when I was in my early teens

During the 70s my list built slowly but surely thanks to European holidays, but in 1978 it got its first major boost with a three-week holiday in California. I can still recall the thrill of that first morning outside San Francisco, surrounded by new birds. I got 42 lifers that day. Fantastic!

A proper checklist was now needed, so I acquired a copy of Clements’s checklist Birds of the World, and this was to be my base for the next decade. It was a busy one, with birding trips not only to Europe, but also Central America, East, West and Southern Africa, South-East Asia and Australia. It was during this period that I took part in a bird race in Kenya, where I saw 290 species in one day, 442 in two. Thus in 48 hours I’d seen more species of birds than most people see in a lifetime in Britain.

Hamerkop, an interesting bird for world listers as it’s in its own unique family, Scopidae

By the 90s I hadn’t lost my appetite for seeing new birds, but I did enjoy going back to places where I could identify the birds myself, without being told what they were. Though trips to Borneo, Argentina and Sri Lanka gave plenty of new ticks, I most enjoyed birding in Africa.

In the early 80s I led a trip to South Africa when we saw more than 400 species. For two of my group – Michael Lambarth and Sandra Fisher – this was their first serious birding trip, and they were bitten by the bug. By the time Sandra died, she was second only to Phoebe Snetsinger as the world’s second highest lister, while Michael was up there in the top ten, with well over 7,000 species. No, they weren’t skilled birders, but they did have the time and the money needed to travel the world and hire the best guides.

It took a trip to Kazakhstan to add Red-faced Bunting to my world list. I’ve never seen this species anywhere else

Which is what a world lifelist is all about. It has little to do with birding skills, but is mainly about opportunity and money. I’ve been lucky, as I’ve led tours all over the world so my list hasn’t cost me a fortune, but for most serious listers their total is simply a reflection of the depth of their pocket. I don’t know how much Phoebe Snetsinger spent on accumulating her list, but it must have been many hundreds of thousands of dollars, and the same goes for nearly all of the big listers.

One for the list: an immature Armenian Gull, Larus armenicus, in Georgia. Not, perhaps, the most memorable of birds, but a recent split from Yellow-legged Gull

If you’re a keen lister, then it’s essential to follow all the latest taxonomic changes. When I went to Kenya in 2001 it was my first visit for eight years and most of my new birds from that trip were simple taxonomic splits from previous trips. Then when birds do get split, there’s the dilemma of working out when you first saw one or other of the split.

Taiga Bean Geese with Greater White-fronted Geese. Taiga Beans are a recent split – they were formerly lumped with Tundra Bean Geese as one species

A classic example is provide by the Bean Goose, now split into two species, Tundra and Taiga. I saw my first wild Bean Geese at Slimbridge in 1974, but were they rossicus (Tundra) or fabalis (Taiga)? I haven’t a clue, though as they were associating with Whitefronts they were probably rossicus.

Hooded Crow, now lumped with Carrion Crow (below)

My lifelist is now somewhere north of 4,000 species, though I haven’t added it up for a long time. I also need to do some serious work with the latest AviList to check the status of birds that have been split, like the Bean Geese, or lumped, like Carrion Crow and Hooded Crow. However, if, instead of seven trips to Kenya, I’d done just one, and gone instead to Nepal, Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Indonesia, China and New Guinea, my list would be well over 5,000, and probably well past 6,000. But I’m not complaining, as I can remember most of the birds on the list. OK, not all of them, but at least 2,500 of them. As for the Firewood Gather, well, I can’t recall a thing, but my lifelist tells me that I saw it in Argentina in November 1994.

So true how much opportunity and resources play a part in the accumulation of big lists. Thank you for writing this, I really enjoyed reading it.

Another enjoyable column David. Thank you.

Excellent and very true. Thank you for this.