The Sri Lanka Grey Hornbill is – unsurprisingly, given its name – a Sri Lanka endemic.

To bring the point home, the scientific name is Ocyceros gingalensis, and Singala apparently is French for Sri Lanka. Not that I would really know – though I once did a year of French in high school, I tend to agree with Dorothy Parker’s apocryphal description of the French language as “a venereal disease of the tongue”. On the other hand, France is currently the 11th-biggest country among the readers of 10,000 Birds, so I should probably be careful.

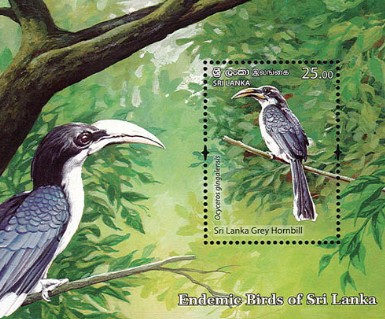

Males and females can be distinguished by the color of the bill – apparently, the females are more fond of black, as it better matches their feathers.

Typically, Sri Lanka Grey Hornbills nest in a tree cavity, in which the female encloses herself and is fed by the male through an opening.

An alternative arrangement is described here – the hornbills using a large aluminum flower pot in a suburban garden as a nesting location (the source also has some nice photos of juveniles).

According to another paper, this suburban nesting is already a bad sign as it may indicate the loss of good breeding conditions in the forest.

Nevertheless, the species is listed as Least Concern.

Compared to the other Sri Lanka hornbill species, the Malabar Pied Hornbill, the Sri Lanka Grey Hornbill is forecast to be relatively unaffected by climate change – perhaps a reason why I did not see any individuals of the species driving around in electric vehicles.

The study analyzing this is surprisingly modest compared to what is often claimed in the last sentence of scientific abstracts: “This study provides supporting evidence for the possible influence of climate change on hornbill species distribution.”

While I have no idea how much value Sri Lanka attributes to individuals of the species, its value on an old local banknote is only a bit more than 3 US cents …

… though it is worth a bit more on a stamp (about 8 US cents).

The carpenter in me wants to travel to Sri Lanka and start building nest boxes. Or maybe I just want to visit what is obviously a very nice place.