Birds are under attack from a large variety of parasites, and have consequently developed a number of strategies against them. A review groups them into five categories:

- Body maintenance (e.g., preening, bathing, scratching, sunbathing)

- Nest maintenance (e.g., removing parasites, site selection, nest abandonment)

- Avoidance of parasitized prey (for example, oystercatchers avoid eating the largest cockles, which are likely to be infested with parasitic helminths)

- Migration (which works partly due to something cruelly called ‘migratory culling’: highly infected individuals die during the stressful migration, reducing the infection risk of survivors

- Tolerance (e.g., compensation for the parasite infestation – infested chicks beg for more food)

And a few of these – particularly in the first two categories – involve chemicals. Let’s look at them.

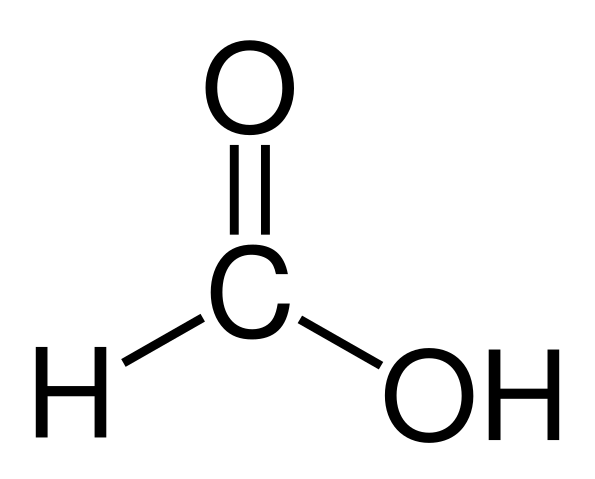

One of the ways some bird species maintain their body health is a behavior called anting. Birds rub ants on their feathers or allow ants to crawl over them. This delivers formic acid, which is secreted by many ants, directly to the feathers. And the formic acid then acts as an insecticide against feather mites and lice. It probably also has antibacterial and antifungal properties.

Formic acid, the simplest carboxylic acid. It is even named after ants (formica is Latin for ant)

Bird species known to practice anting include jays, crows, and thrushes, possibly even owls.

A broader definition of anting (found here) includes the deliberate skin and plumage application of pungent substances other than formic acid, such as citrus fruits (which contain aromatic oils) or mothballs (naphthalene or paradichlorobenzene).

The same source argues that anting serves some function that favors it despite the increased risk of predation, as birds are often easier to approach when engaged in it.

Nest maintenance and sanitation is the second area in which birds use specific chemicals to defend themselves or their nestlings against parasites.

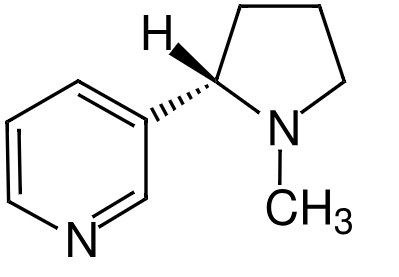

A well-described example is the active incorporation of filters from smoked cigarettes into bird nests. There is evidence that the nicotine in the cellulose acetate filters repels parasites. A follow-up study on house finches in Mexico City showed that they bring more filters to their nests if the parasite load is higher.

Nicotine, a chiral alkaloid and a known repellent (after all, the tobacco plants produce it as a defense mechanism against herbivores and insects).

Unfortunately for the birds, the nicotine also induces genotoxic damage in chicks and parents.

Many birds collect plants containing active chemicals to line their nests. This reduces the parasite load of both adults and chicks. Generally, the chemicals released are volatile organic compounds with a repellent or toxic effect on parasites such as fleas and mites.

Here are some examples of plants with their relevant chemicals:

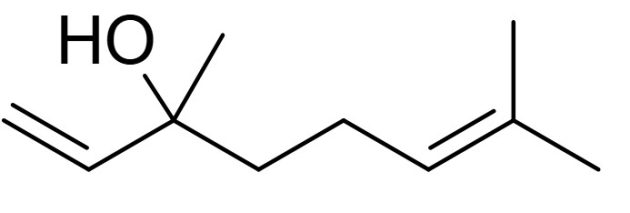

Lavender contains Linalool, a terpene alcohol which has insecticidal and antifungal properties. Blue Tits have incorporated lavender into nests, leading to healthier nestlings (source).

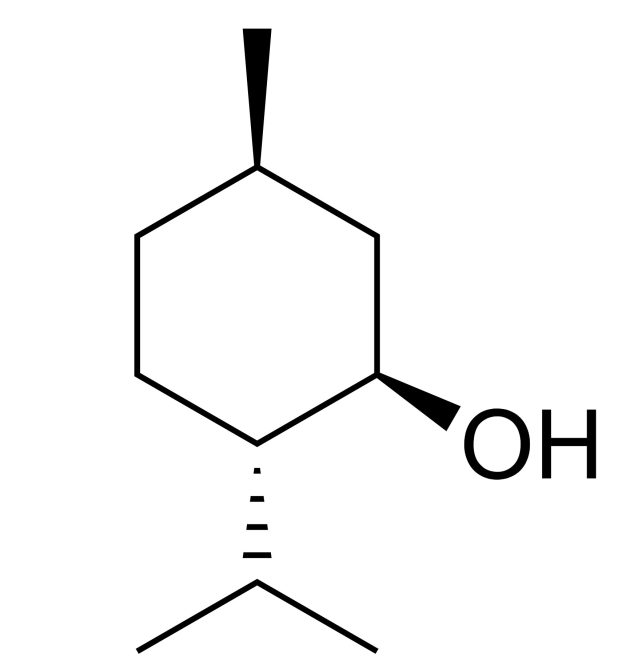

Mint contains Menthol, a monoterpenoid with antibacterial properties. When experimentally adding mint to the nests of Great Tits, the condition of the nestlings improved (source).

Yarrow: contains various Alkaloids, Monoterpenes, Sesquiterpenes, and Flavonoids with insect repellent, insecticidal, and antimicrobial properties. Yarrow is used as nest-building material by Common Starlings (source). And while it is not naturally incorporated into the nests of Tree Swallows, experimental addition to their nests reduced the number of parasites (source).

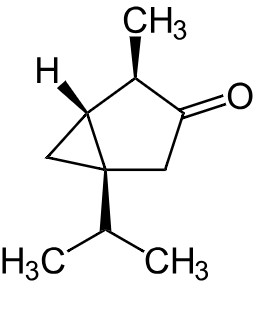

Wormwood: contains Thujone, a monoterpene ketone known to be toxic to arthropods. A study on Russett Sparrows in China found that they incorporate wormwood in their nests, and that this leads to healthier nestlings.

These examples show that some birds use chemicals to repel parasites, thus improving the health of adults and chicks.

Nicotine also induces genotoxic damage… reason not to light another one, I’d say. If you have ever seen the biting insects in a nest box you know how vicious some of these parasite are. Nature isn’t a nice place. I always feel like I need to give the birds access to something like DDT. Seems like they already figured out something without my help. 😉