Hummingbirds are quite popular with birders (though not all of them—some think they are overrated). They are admired for their iridescent beauty and their flight abilities. But from the viewpoint of a chemist, their metabolism is equally impressive, as they are uniquely capable of rapidly processing sugars and shifting to another energy source, fat. This metabolic flexibility enables their sustained hovering and quick movements.

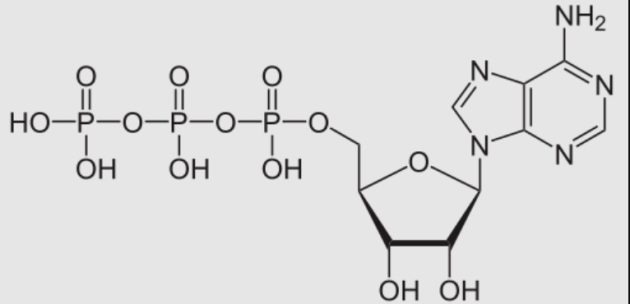

Hummingbirds rely heavily on floral nectar, composed mainly of sugars, particularly sucrose. They can digest and use this sugar almost immediately after ingestion, supported by exceptionally high sucrase activity. Sucrase breaks sucrose (a disaccharide consisting of two linked simple sugars) into glucose and fructose, which can directly enter the bloodstream and reach the flight muscles, where they are used to produce ATP. As a result, a hummingbird can fuel much of its hovering flight with sugars consumed only minutes earlier—a form of near-real-time energy use rarely seen in other birds.

ATP, Adenosine triphosphate

When nectar intake stops, even briefly, hummingbirds depend on stored energy. Most vertebrates—including humans, who are not generally known for their iridescent beauty—shift between carbohydrate and fat metabolism slowly, but hummingbirds can make this transition rapidly, guided by hormonal signals that reflect nutrient availability. When no sugars are available, metabolism shifts toward the oxidation of stored fats. Though hummingbirds carry only small fat reserves, these are mobilized efficiently, supporting continued activity when feeding is interrupted. This ability to change fuels quickly is one of the most distinctive aspects of hummingbird metabolism.

But what about nighttime? Because of their exceptionally high daytime metabolic rates (all the hovering and flights from flower to flower), hummingbirds would soon deplete their energy reserves if they maintained the same pace while roosting. Some hummingbird species avoid this problem by entering torpor, a controlled reduction in body temperature, heart rate, and metabolic rate. In this state, energy consumption drops sharply, and fat oxidation becomes the primary energy source. Torpor thus means the biochemical processes shift from high turnover to conservation of resources.

The metabolism of hummingbirds is closely tied to the demands of hovering, which requires continuous high-level energy provision. This can only be achieved via high sugar consumption and efficient oxygen delivery. Hummingbird flight muscles achieve this through very high mitochondrial densities, rapid calcium cycling during contraction, and an oxygen transport system adapted for constant, intense activity. Together, these systems enable a form of flight that is uncommon in other bird groups.

The ability of hummingbirds to use nectar sugars almost immediately, transition quickly to fat metabolism, and reduce energy needs through torpor are all based on chemical processes. So, at least chemical engineers should highly appreciate this family.

Photo: “Costa’s Hummingbird (male)” by steveberardi is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Leave a Comment