We’re birders and we’re used to seeing feathers. They may be stray feathers from a Northern Flicker, the yellows shining in the grass, or the grayish remains of a Mourning Dove, probably preyed on by a Cooper’s Hawk, or a piece of fuzzy down falling from a nest you didn’t realize existed. Birding on my favorite beach this summer, I walked along a line of small, white feathers, probably from the molting Common and Foster’s Terns who frequent the nearby mudflats. We see feathers far less than a nonbirder might imagine, and they are usually there for a reason. If we pick one up, we’re likely to hear someone caution that it is illegal to take feathers under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, so we take photos and measurements and try to identify what bird the feather belonged to, usually with the help of an online feather guide, and try to figure out why it’s no longer a part of that bird. For Roxie Collie Laybourne, however, feathers were a biological challenge, a lifelong passion, and a way to make the world safer for people and wildlife.

©2025, Donna L. Schulman, probable Common or Forster’s Tern feathers, Suffolk County

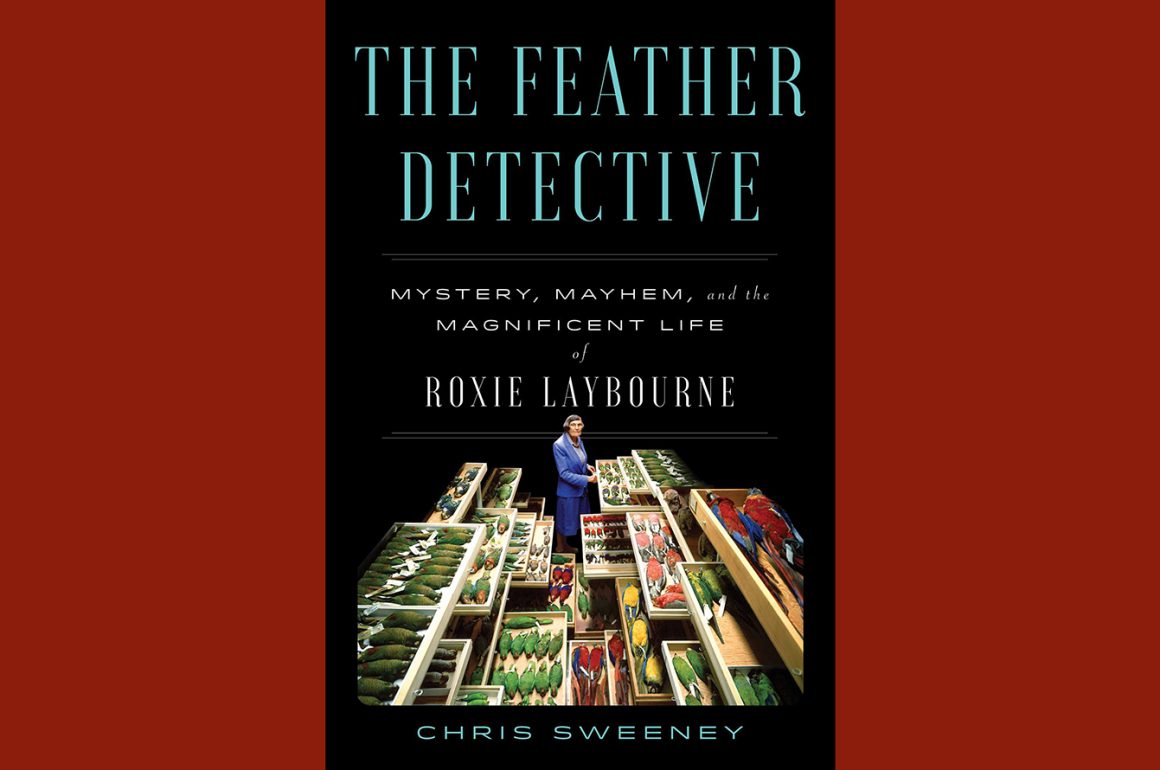

In the bird room at the Smithsonian Institute, Roxie studied feathers using techniques she had invented and tested early in her career. She testified at criminal trials and wildlife protection investigations; she was key to developing aeronautic standards and policies for avoiding bird strikes, preventing horrendous plane crashes, and protecting Army test pilots; the mountain of data she sent to the government became the core of the FAA Bird Strike Database. She created a forensic science that scientists, aviation professionals, and government officials didn’t know they needed. In The Feather Detective: Mystery, Mayhem, and the Magnificent Life of Roxie Laybourne, Chris Sweeney presents the life of this singular scientist. It’s a fascinating read. It’s not easy to tell a scientist’s story, but Roxie wasn’t an ordinary scientist. Sweeney does a great job illustrating the diverse facets of her work and her personal history, emphasizing her pioneering status as a woman research biologist in the Smithsonian’s Division of Birds and her significant role in educating and mentoring men and women in this very niche, crucial field.

There are many stories told in this book, but for me the one that most resonated is related in the second half of the book, when Roxie, 77 years old and still working for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, becomes part of a raid on the Virginia estate belonging to billionaire John Kluge. It’s a shocking story, about gamekeepers who established a “Shoot” for Kluge’s wealthy, jet set friends, and in the process shot and killed 91 Red-tailed Hawks, seven Cooper’s Hawks, five Great Horned Owls, three Turkey Vultures, two Killdeer, one Red-shouldered Hawk, one Barred Owl, one crow, and one snipe plus dogs of neighbors, all in the name of “protecting” the pheasants needed for the shoot (p. 199). Most of the bird remains were found in two large pits; Roxie’s job, with the assistance of her protege Beth Ann Sabo (who talks about the event in the Criminal podcast), was to sit by the rank smelling pit and identify and document the sad remains, providing proof that the birds shot were protected by law and that the gamekeepers were committing felonies. Roxie, according to Sabo, was very matter of fact about an investigation that one young Wildlife agent called “one of the vilest crime scenes he’d ever worked” (p. 198). As horrible as it was, there is something very satisfying about this story in which the federal government holds one of the richest men in the U.S. accountable (though Kluge did manage to distance himself from the crime, his reputation was temporarily tarnished) and knowing that a bird loving lady (because Roxie was a birder at heart and in practice) was an important part of that effort.

Roxie Collie was born in 1910 and raised in Fayetteville, North Carolina, the eldest of 15 children. (Recordings show that she held on to her deep Southern drawl into old age, a characteristic that Sweeney thinks may have contributed to the scientific and government world not always taking her seriously. You can hear her on the podcast Criminal, which devoted an episode to her forensic exploits in 2023, utilizing excerpts from her Smithsonian oral history.) After attending Meredith College, a small women’s college in Raleigh, during the Great Depression, she worked for the North Carolina State Museum of Natural History, mostly as an unpaid taxidermist and exhibit preparer, till a graduate school professor directed her to a war-time job as a taxidermist in the Smithsonian Institution’s Division of Birds in Washington, D.C. Two years later, the war was over and the appointment was too. Fortunately, Roxie found a new position with U.S. Fish and Wildlife, ironically, still working in the bird room at the Smithsonian. She obtained a master’s degree in botany from George Washington University, but never completed her ultimate goal of a Ph.D. Family and work got in the way. Roxie married twice and raised two sons, though motherhood, by her own admission, was far more challenging than being the only woman biologist in the Division of Birds.

Roxie Laybourne stands behind the counter in the Birds Division with dozens of a single species of songbird laid out in rows. She holds one in her hand and looks at the camera. Smithsonian Institution Archives, Acc. 04-086 Box 2, Folder 5; [SIA2014-07445]

Remarkably, much of this work took place after 1974 when Roxie was forced out from Fish and Wildlife by a nasty administrator. Roxie continued to work in the back of the Bird Room as a Smithsonian research associate, a title which allowed her access but not a salary. According to Sweeney, she operated “a one-person consulting firm from her small, cluttered office in the back of the bird collection…charging typically around $250 per feather identification” (p. 153). She also worked three days a week for Fish and Wildlife’s Office of Law Enforcement, finally retiring in 1988. But still she worked in the back of the bird room! When physical impairments forced her to stay home on her farm in Manassas, Virginia, she continued to advise, mentor, and identify feathers, with the help of the ornithologists she had trained to take her place, till her death in 2003.

A long life, a long, noteworthy, pioneering career. The question for the biographer is how to take this material and create a narrative that engages the reader. Fortunately for Sweeney, there is a lot of material: oral history tapes recorded by the Smithsonian’s institutional historian on eight visits to the Manassas farm, a Meredith College oral history, Smithsonian archival records, newspaper articles about Roxie’s FBI criminal and wildlife criminal cases. Many of the people who worked with Roxie in her later years were available for interviews. Sweeney, a journalist who has written for Audubon Magazine, The Guardian, and Popular Science, amongst other publications, smartly focuses on the dramatic stories associated with Roxie’s work. The deadly plane crashes, outrageous wildlife slaughters, violent murders of women, boyfriends, civil rights activists become tent poles on which to string Roxie’s story, as well as detailed illustrations of her hard work and dedicated intelligence.

Sweeney seems to have relished researching and writing background histories for the diverse fields and institutions in which Roxie operated. We learn about the early aeronautics industry, the roots of the Smithsonian Institution (I had no idea it was originally funded by a bequest from an Englishman named Smithson), and the British brothers who transformed the North Carolina State Museum. Ironically, the one area we don’t learn much about is how bird skins, the scientific specimens whose preparation started Roxie’s career and which she used unstintingly for feather identification, are an essential resource for taxonomic, morphological, anatomical, evolutionary, and medical research. This might have given a wider context for understanding the environment in which Roxie operated for most of her work life.

Sweeney does struggle to portray Roxie, the person, inside Roxie Laybourne, the forensic scientist. She was in many ways a contradiction. Her articulated work mantra was “Do the work, keep your mouth shut, and they will respect you” (p. 73), yet she insisted on doing her work her way, even when her job was eliminated. Her feather identification process involved long hours of observation of microstructural patterns and systematic comparisons, yet her work area was notoriously cluttered and messy. She worked alone for most of her career, but she enjoyed attending ornithological conferences and their social functions (well, maybe that isn’t a contradiction!). The portrayal of Roxie’s personality and relationships becomes more insightful and complex as the biography progresses into her later years and Sweeney can use sources other than Roxie’s own words. Her proteges and late life colleagues appear to be delighted to talk about her and she emerges as a sometimes cantankerous, sometimes charming, singularly obsessed woman who inspired deep respect, wonder, laughter, and devotion. I’m glad we have this biography to document her unique career and remarkable life.

Portrait of Chris Sweeney ©Kent Dayton, 2025

The Feather Detective: Mystery, Mayhem, and the Magnificent Life of Roxie Laybourne

by Chris Sweeney

Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster, July 2025

320 pages, illus.; $30.00; eBook, Kindle, & Audio book formats also available

ISBN-10 : 1668025841; ISBN-13 : 978-1668025840

Had not heard about this book Donna. Definitely my kind of reading. Thanks for this intro profile of Roxie Collie and for such a thorough review. To me your final paragraph portrayal of Roxie is of precisely the kind of person we need to do this kind of work. If not for her, and people like her, who would do the detail work that is behind, well, everything. Born in 1910, the eldest of 15 kids, crazy, as in amazing! I am going to look for this book. I must admit I would prefer paperback for reading, but I am definitely going to check it out at Barnes & Noble today. Will need to order, of course; but at least it’s not Amazon.

Excellent review of what appears to be an excellent book. Thanks, Donna. (Am a retired public librarian and obsessive birder.)

Got the book! B&N had one copy in stock. Decided to bite the bullet on hard cover price. Just reading the cover and the first page was enough to take me there.