In “The Restaurant at the End of the Universe” (Douglas Adams), a cow introduces itself to the diners with the words “I am the main Dish of the Day. May I interest you in parts of my body?”

Unfortunately for birds all over the world, most animals suitable as avian prey are far less accommodating. They even resort to chemical warfare just to avoid being eaten. Some birds think this is grossly unfair and point out the prohibitions of the Geneva Convention, but without much effect. So, let us ignore the morals of this defense and look at the chemicals used by different groups of animals.

Insects

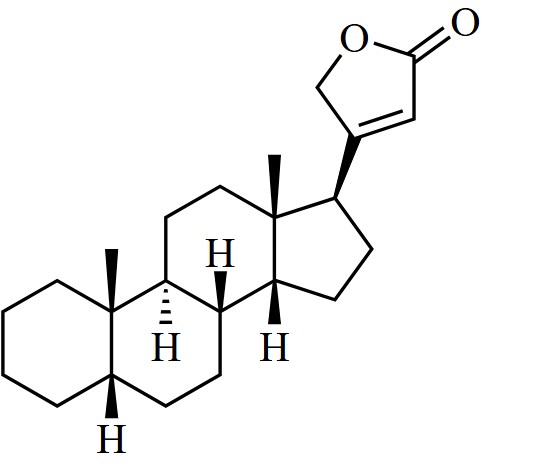

Milkweed butterflies ingest cardenolides (a type of steroid) contained in the milkweeds that they mostly feed on. This cardenolide deters most predators, except a few that have evolved to become cardenolide-tolerant, such as the black-backed orioles. Other birds, such as starlings, learn to avoid these butterflies after eating them once and experiencing vomiting and distress.

Cardenolides are toxic to animals through inhibition of the enzyme Na+/K+-ATPase, which is responsible for maintaining the sodium and potassium ion gradients across the cell membranes (source).

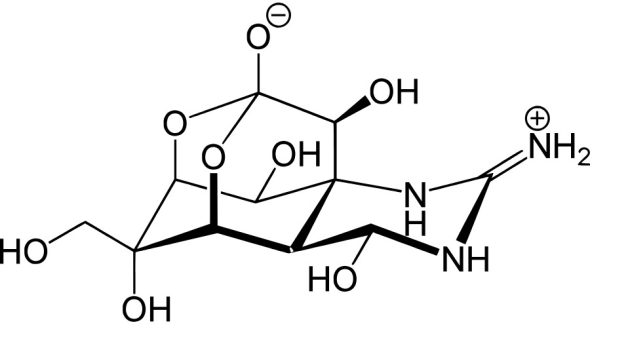

A cardenolide. Cardenolides are C(23)-steroids with methyl groups at C-10 and C-13 and a five-membered lactone at C-17

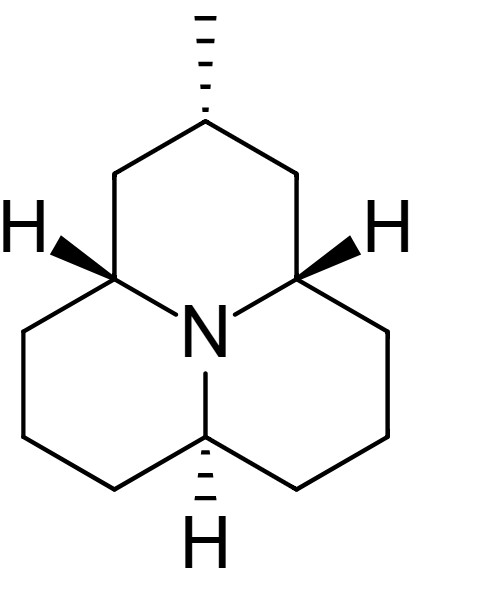

Ladybird beetles (these are the cute red ones with the black dots) secrete an alkaloid-rich venom from their leg joints. Chemically, it consists of coccinellines – alkaloids composed of three fused piperidine rings that share a common nitrogen atom (source). These taste bitter and are toxic to many birds.

Precoccinelline, an alkaloid produced by the seven-spot ladybird

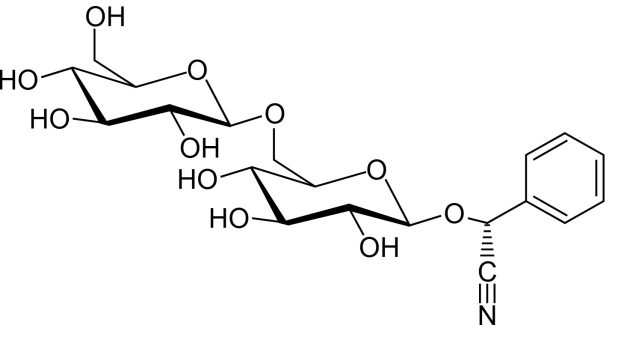

Burnet moths contain cyanogenic glycosides that release cyanide when crushed, which has been shown to lead to rejection by chickens (source). Interestingly, the moths can both deal with cyanogenic glycosides produced by plants (i.e., they are not poisoned by them) and have also developed their own internal way of synthesizing them as a chemical defense (source).

Amygladin, a cyanogenic glycoside. Note the -CN group that can be released as cyanide.

Amphibians

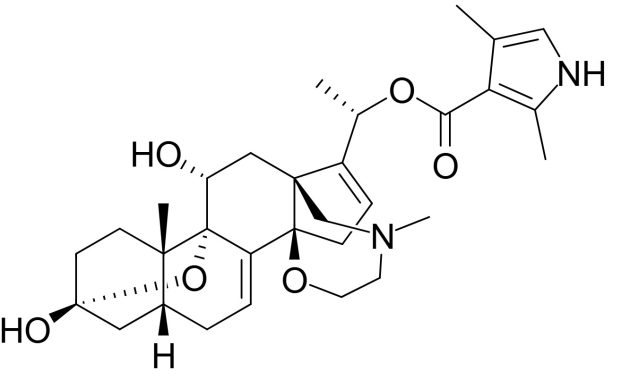

Poison dart frogs contain poisons such as batrachotoxins, which are highly toxic to birds. And yes, the name comes from some Amazonian hunters using the frogs’ secretions to poison the tips of blowgun darts. The frogs get the toxin from batrachotoxin-containing insects that they eat, and then secrete it through the skin. Interestingly, there are even a few birds (pitohui) that are toxic based on the same process and toxin.

Batrachotoxin, a cardiotoxic and neurotoxic steroidal alkaloid. It opens the sodium channels of nerve cells and prevents them from closing, resulting in paralysis and death (source).

Many tropical birds, including motmots and jacamars, therefore avoid brightly colored frogs (which even leads to some non-toxic frogs adopting similar warning colors).

The rough-skinned newt produces tetrodotoxin, which can kill birds if they swallow a whole newt. The working mechanism is similar to that of batrachotoxin.

Tetrodotoxin

Reptiles

Some snakes, such as gartersnakes, eat toxic newts and, rather than being poisoned, sequester the tetrodotoxin and become toxic themselves.

Marine Animals

Both pufferfish and blue-ringed octopus are also toxic due to tetrodotoxin, most likely via ingestion of tetrodotoxin and/or tetrodotoxin-producing bacteria (source). One paper describes a Great Egret catching and immediately releasing a toxic pufferfish “with bill washing and discomfort movements afterwards”.

There are many other examples in the different categories, whether caterpillars, bombardier beetles, and bees for insects, fire salamanders for amphibians, or the thiols used by skunks to deter raptors.

Birds generally quickly learn to avoid toxic prey, with their learned prey aversion often lasting lifelong. Poisonous species also often advertise their toxicity using bright colors.

Photo: “Poison dart frog, Excidobates condor, Dendrobatidae” by In Memoriam: Ecuador Megadiverso is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

I saw a pair of Black-backed Orioles just today. I had no idea they are poison resistant.