Two birders I know visited Greenland last year, 2025, which is two more than before 2025. Greenland has historically gotten short shrift from birders, who usually opt to visit Iceland, 180 miles away (using their closest points) when looking for pristinely beautiful, icy landscapes with few passerines and many alcids. But the country, a territory of Denmark with self-rule, has been in the news, and its visibility may have sparked interested from ecotourists. There is little about Greenland in the birding literature, one of the reasons I welcomed the opportunity to review The Seabirds of Greenland. This large book with stunning photographs, many full-size, has all the basic characteristics of a scrumptious ‘coffee table’ book, yet it also features articles by research scientists, giving it an authenticity and depth that many coffee table books lack. The authors’ aim “is to try to share our fascination with seabirds,” to answer questions “you may have after a trip along the coast of Greenland–or on your couch at home,” and, I think, to make a case for the unique value of this major resource and why it should be conserved and treasured. It’s important to note that all proceeds from the sale of this book will go back into more research, via the Oceans North Kalaallit, a Greenlandic NGO, another major reason why I wanted to do this review.

Organized into nine chapters that artfully balance text and photographs, The Seabirds of Greenland is about the seabirds themselves; the ways in which they are studied; the biological and behavioral adaptations that protect seabirds from extreme cold and enable them to nest on land and live in the sea and on the air; the ecology of the seabird food chain (complete with cool diagrams); the seabird life cycle (long lives, long youth, long term pair bonds, few children, sharing of childrearing responsibilities, breeding in colonies that are often crowded but have a great view); migration; the long-term, changing relationships of seabirds with the people of Greenland; effects of climate change on the seabird life cycle and food chains. Topics are expanded and enriched by illustrated information boxes, some encompassing two full pages, that focus on specific topics: The Master Diver, an in-depth look at Thick-billed Murre; The Two Most Important Fish in Greenland (capelin and polar cod, both eaten by birds and people); SEATRACK, the collaborative research project that processes data from light loggers to track seabirds in the North Atlantic; Qoororsuaq, Little Auk Valley, an isolated area chock full of Little Auks (Dovekies) where researchers find the remnants of an early hunting settlement are just some examples. This is a book that can be read sequentially or, my preference, by artful browsing, though the size and weight make it tricky to read while watching television (probably a good thing, forcing me to focus).

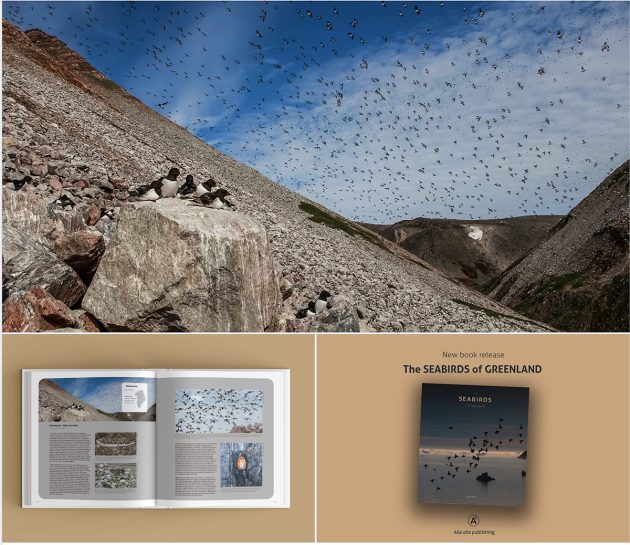

©2025, The Seabirds of Greenland, Alle Alle Publishing, pp. 92-93; photograph of the Little Auks of Qoororsuaq (Little Auks Valley) by Carsten Egevang, the original photograph and how it is used in the book; the other photos are by Egevang and Kasper Lambert Johansen (from Carsten Egevang’s Facebook site)

The authors have made an effort to limit technical scientific language and provide a Glossary in which unavoidable terms like “permafrost” and “tropic mismatch” are defined at length. There is also a list of books and articles for Further Reading, including popular science books like Far From Land: The Mysterious Lives of Seabirds by Michael Brooke (highly recommended) and scientific journal articles on seabird species and Greenland’s seabird ecology, many by co-authors of this book. The list of book authors is impressive. At the top of the credits is Morten Frederiksen, professor at the Department of Ecoscience at Aarhus University, Denmark, whose research on seabird populations, their movements and behavior as tracked by data loggers, is based in Greenland and Denmark. Federiksen is overall editor, author of the Introduction and chapters on challenges and adaptations, seabird food chain ecology, seabird life cycles, and migration, co-author of chapters on seabird species, research techniques, and climate change. Additional authors are David Boertmann, Carsten Egevang, Kasper Lambert Johansen, Aili Lage Labansen, Jannie Fries Linnebjerg, Flemming Ravn Merkel, and Anders Mosbech, most of whom are associated with Aarhus University, Greenland Institute of Natural Resources, and other Arctic-related research projects.

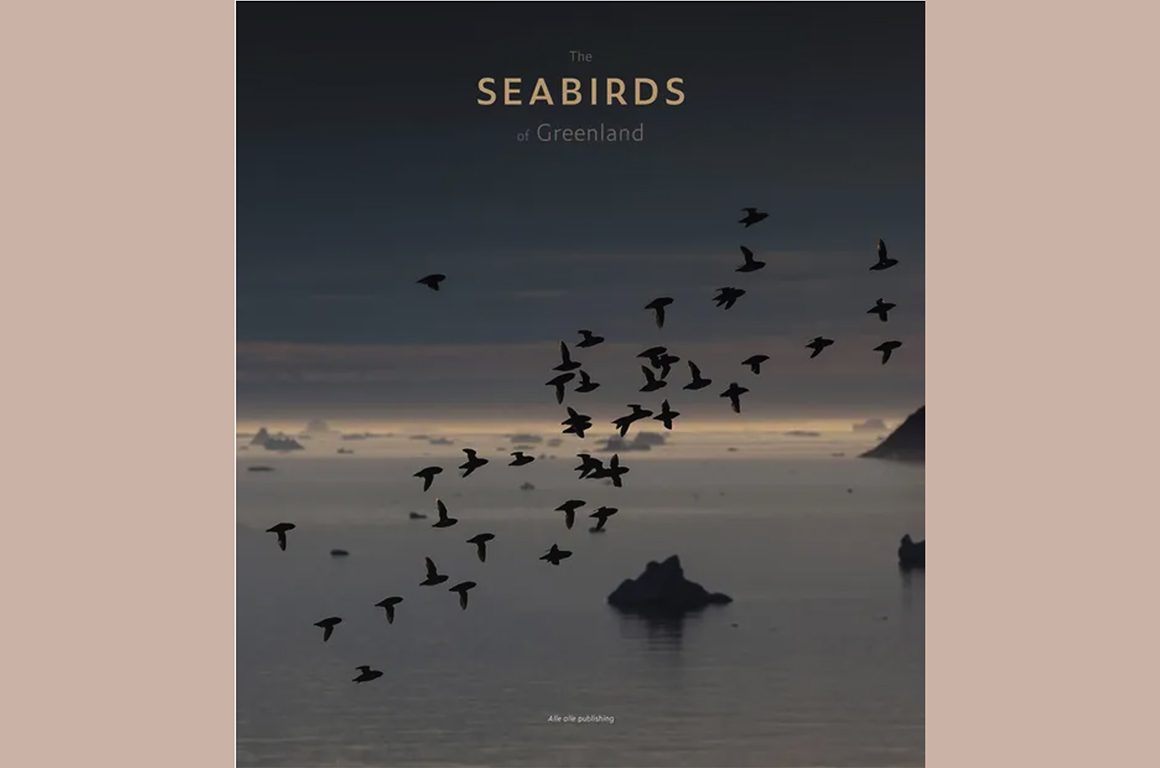

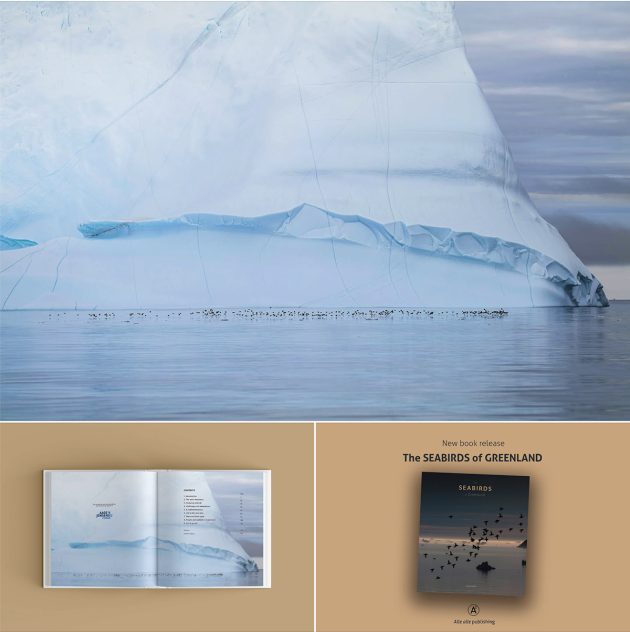

Carsten Egevang is the other major player in this book’s production. With a background in Arctic biology (his Ph.D. research resulted in the discovery that Arctic Terns make the longest migration journey of any animal in the world), Egevang is a passionate documenter and interpreter of Greenland’s birds, mammals, land, and people. His publishing company, Alle alle, has published four books about Greenland, including this one. His photographs in The Seabirds of Greenland are incredible, showing technical details and evoking a spirit of wildness and wilderness, the outer edges of the world and the inner lives of little-known, dream-like birds. I wish I could reproduce them all in this review. One of my favorites is a two-page image of a snow-covered mountain outside of Ittoqqortoormiit, a remote town in southeast Greenland, taken in July, found on pages 144-45, at the end of the text chapters. The white-bluish mountain edge curves gently down from the upper left corner to the bottom of the right page, contrasting with a blue-gray muted sky, and in the bottom third of the left page we see a snowy crag jutting out from the snowy mountain and on that crag we see about 24 black-and-white creatures–Kittiwakes, the label tells us. The image beautifully conveys the monumental wildness of Greenland poised against the vulnerability, the total smallness, and utter strength of its seabirds. The image below, of Little Auks at the mouth of Scoreby Sound, is very similar, though it appears in the book as background for the table of contents. Authors Morten Frederiksen, David Boertmann, Jannie Fries Linnebjerg, Kasper Lambert Johansen, and Flemming Ravn Merkel contributed photographs, as well as Knud Falk, another Arctic researcher, and Henrik Haaning Nielsen, ornithologist and bird guide.

© 2025, The Seabirds of Greenland, Alle Alle Publishing, pp. 2-3; Little Auks at the mouth of Scoresby Sound, photograph by Carsten Egevang, the original photograph and how it is used in the book (from Carsten Egevang’s Facebook site)

© 2025, The Seabirds of Greenland, Alle Alle Publishing, pp. 2-3; Little Auks at the mouth of Scoresby Sound, photograph by Carsten Egevang, the original photograph and how it is used in the book (from Carsten Egevang’s Facebook site)

Amongst the riches here, I was most fascinated by the section profiling seabird species and the later chapter discussing the complex relationship between seabirds and people. There are only 253 species on the Greenland checklist, 178 of them rare, accidental, extinct, or extirpated. Which makes it not surprising that the eBird checklist lists 116 species. Of these, the authors designate 33 species as “seabirds,” using the ecological, broad definition of “those species that primarily rely on resources–i.e., food–from the sea,” but not including species that feed along the shore (p. 11). These “main characters” are 28 regular breeding species and five species that occur in Greenland’s waters outside the breeding season; they include waterfowl, gulls, skuas, and terns, auks (alcids), tubenoses, divers (loons), and cormorants. Of these, six species get special attention because of their importance to Greenlandic ecology and society: Common Eider, Ivory Gull, Black-legged Kittiwake, Arctic Tern, Thick-billed Murre, Little Auk (Dovekie). They are profiled in two-page information boxes in this and other chapters. These are the species on which the authors’ research has focused, and which define Greenland’s seabird life.

Here are some information nuggets I’ve learned from these species profiles: Kittiwakes are easy to capture, which means they’ve been studied extensively in many countries. Although their populations have declined steeply in Norway, Scotland, and Iceland, their numbers have increased in parts of Greenland, a phenomenon thought to be due to an imbalance in marine ecosystems (climate change at work) that has increased the number of small fish favored by Kittiwakes and decreased the number of larger fish eaten by Little Auks. Thick-billed Murres breed in large cliff colonies that number up to 100,00 pairs, sometimes even more. They are densely packed in, but have deep nest site fidelity, “even moving 10-15 cm to the next place in line is a rare occurrence” (p. 24). Happy news for researchers, who need to recapture birds tagged with electronic data loggers! They also dive deeper than any other flying bird, their bodies made for diving, not flying, which they don’t do much in non-breeding season. The Ivory Gull (possibly my favorite gull in the world) is “a true opportunist” and will eat anything, from fish to seal remains to human refuse (p. 63). Such an elegant bird, such a non-discriminating palette! They’re flexible about nesting places too, except that they won’t nest in a place hosting predators. Tiny islands, drifting icebergs, gravel on top of a glacier–all good for the nest as long as an Arctic Fox doesn’t come along. Smart bird.

The chapter “People and seabirds in Greenland” covers a wide swath. There’s the history of bird hunting amongst the early Saqqaq and Dorset cultures, later amongst the Inuit, who developed specialized bird spears. The Inuit use of bird skins for various types of clothing–an inner layer with feathers turned towards the skin in winter, more decorative tops with feathers turned out in summer months. A trade in eider down in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Large scale commercial trade of Thick-billed Murres in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Common Eiders and Thick-billed Murres as significant food sources from early times through the 20th century, hunting becoming more efficient with faster boats, spurring regulations to stem bird population declines. Bird hunting and egg gathering as nature-related activities, along with seal hunting, fishing, and gathering berries, that create community, connection to the past, and identity, spurring resistance to regulation. Add to the sense of identify seabird food dishes, many made by fermenting techniques that involved burying the food in seal blubber or simply buried under rocks. It’s fascinating stuff and the statistically oriented section on whether such exploitation is sustainable (it’s not), clearly elides many stories of stress between Greenland’s people and the government and organizations that are enforcing bag limits and other hunting and egg harvesting restrictions. But it seems that Little Auks are still caught the old-fashioned way in the Qaanaaq area, with long-handled nets that look easy to handle but require “tenacity, skill and knowledge of bird behaviour” (p. 20).

The Seabirds of Greenland, edited by Morten Frederiksen is unique, possibly the only book on birds of Greenland published after 1950. Birders traveling to Greenland are advised to use North American field guides–Greenland is part of North America!–but it seems to me that this is a special place that deserves its own bird book. This collection of educational essays by research and field scientists and remarkable photographs by Carsten Egevang and his colleagues is a very good start. The book is large, expensive (you pay for what you get, and these are quality printed photographs) and not easily available from North America (see below for a suggestion), but I think it is worth the effort.

The Seabirds of Greenland

edited by Morten Frederiksen, graphical design & many photographs by Carsten Egevang

Copenhage: Alle alle Publishing, 2025

252 pp., 190 color photographs, 26,5 x 29,5 cm, 60 euros

Text: English or Danish or Greenlandic

ISBN: English: 9788797178072

ISBN: Danish: 9788797178065

ISBN: Greenlandic: 9788797178089

Available from online bookstore NHBS.

Leave a Comment