What do you do when you are a bird guide in a Central American country incredibly rich in birds and other natural resources but which has no birding field guide? You write your own. And, what do you do when you can’t find a publisher? Publish it on your own—in paper, not digitally, with illustrations by three noted nature artists. This is exactly what Robert J. Gallardo did. Guide to the Birds of Honduras is an extraordinary creation, noteworthy for both the excellence of the work itself and the years of work that went into making it a reality.

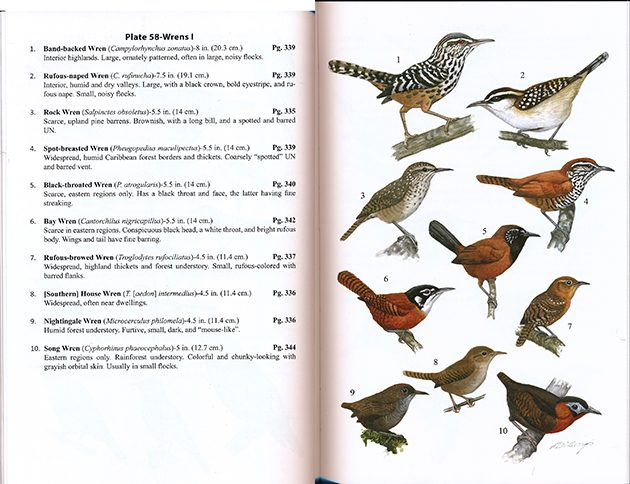

Wrens I by Michael DiGiorgio

Gallardo has been a professional bird guide in Honduras since 2001 and first came to the country as a Peace Corps volunteer in 1993 (his “Chronology of Field Work in Honduras” is a chapter in the book). A friend of 10,000 Birds, he talked to Corey about his mission to create this guide in 2012 and wrote about his goal to create a Spanish-language version of the guide in 2017. Many birders are familiar with Gallardo’s fundraising initiatives, which included a speaking tour in the U.S., selling original art plates, and sponsorships and donations from birding and conservation companies and agencies from the U.S., Europe, and Honduras itself. I hope that he will one day write an article about how it all came together, but I know from social media that he is currently putting the finishing touches on Guía de Aves de Honduras and developing a manual of activities for school children that will be available to Honduran teachers when the book is published.

Guide to the Birds of Honduras was self-published in 2015, text by Gallardo and artwork by John Sill, Michael DiGiorgio, and Ian Griffiths. It gives species accounts for 761 birds (I counted, but I could have missed a couple) out of the 763-770 species documented in the country (eBird lists 763 and Gallardo says there were 770 at the time of publication). Illustrations are old school, in a separate section, with images of the right and brief descriptions of the left–73 plates offering 1,000 images. It’s the book I wish I had had available for study before my trip to Honduras (in 2015, but right before the title was available), and I’m glad Mike’s trip to Honduras earlier this summer prompted me to go to my bookshelf and take a closer look at this significant achievement.

Special Sections

The Guide offers a lot of goodies not ordinarily found in bird identification guides: a chapter on “Bird Migration in Honduras” that covers both the long-distance migration and more local movements; an extended section on “Where to Find Birds in Honduras” that includes a table of GPS coordinates of bird watching hotspots (in a way, you’re getting two books in one); a 16-page table on “Species to be Expected” in Honduras and where they will likely be found; and a list of “Hummingbird Nectar Sources”–a listing of flowers that attract hummingbirds and which hummers they attract, based on Gallardo’s observations.

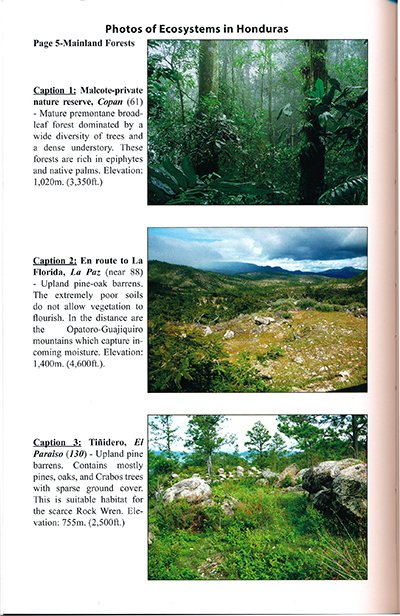

The section on “Ecosystems in Honduras” is located in the central illustrations section; Gallardo has narrowed down the country’s 40 ecosystems to 15–diverse forests and wetlands, from Lowland Rainforest to Arid thorn scrub forest (home on the only endemic, the Honduran Emerald) to flooded forests–and illustrated most of them with 33 color photos. There is a foldout map of Honduras, showing Ecosystems on one side, in deep colored blocks and waves, and Important Birding Sites on the other side, correlated to the bird finding section of the book. And, there is the usual introductory material on bird terms, bird topography, and brief overviews on geology and climate.

Species Accounts

The Species Accounts are arranged in a rough AOS taxonomic order. It isn’t clear exactly which taxonomy of which year was used and there is not table of contents of families, so the best way to find a specific species is to use the scientific and common name indexes in the back of the book. The common name index is, thank heavens, arranged by major name, so if you are looking for a flycatcher but can’t remember which one, there they all are, all 45 species with ‘flycatcher’ in the name, listed in the F section. Each index entry gives the page number of the species account and the plate number in bold print.

A lengthy description of the bird family (or, in some cases, combination of family groups) introduces each family group: traits, number of species in Honduras and in the world, sometimes taxonomic notes, and a description of the family’s status, distribution, migration patterns, habitats, nests, and behavior in Honduras. These descriptions are quite helpful, especially if you are not familiar with the family group. So, for “Typical Antbirds,” we learn that they are often the nuclear species in mixed flocks and that many species found in Honduras are obligate ant followers. Under “Tanagers,” we’re informed that Mountain Apple attracts “an amazing number and variety” of tanagers, and that nearly half of “typical” tanagers are sexually dimorphic.

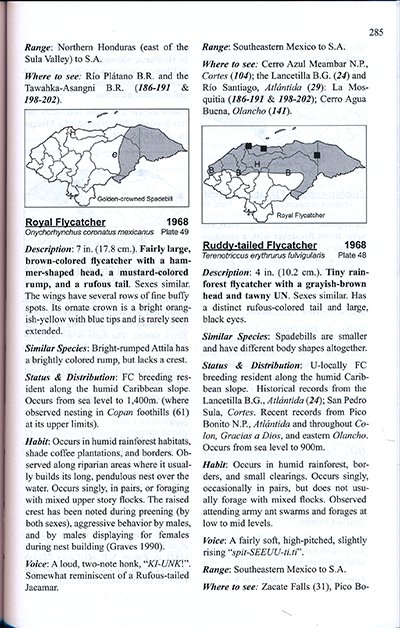

Each specific Species Account gives common name, scientific name, date the species was officially documented in Honduras, and Plate number. This is followed by measurements; plumage description, including separate descriptions by sex and age if required, with distinctive features bolded; Status & Distribution; Habit (i.e., habitat); Voice; Range of species beyond Honduras; and Where to see–places where you are most likely to see the species.

The ‘Status & Distribution’ sections are lengthy for a bird guide (meaning more than two lines of text); in addition to the usual info on migrant, resident, and visitor status, altitudinal range limits are given, plus historical records, unusual sightings, and the author’s sightings. They are accompanied by black-and-white range maps that show distribution (but not migration routes), expanded with codes for recent sightings (often the author’s), eBird sightings, and historical records.

Artwork

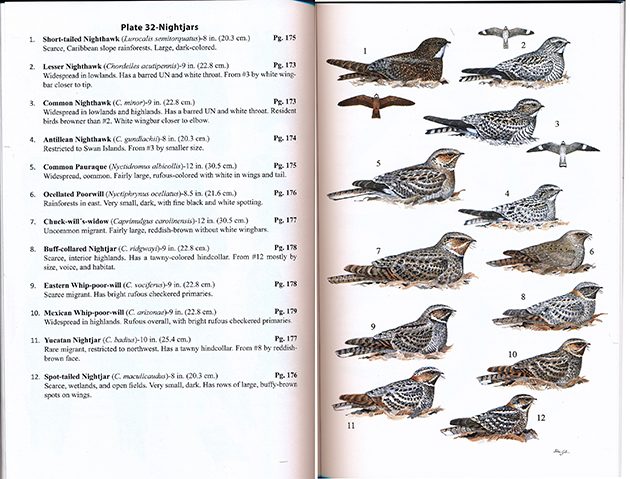

Nightjars by John Sill

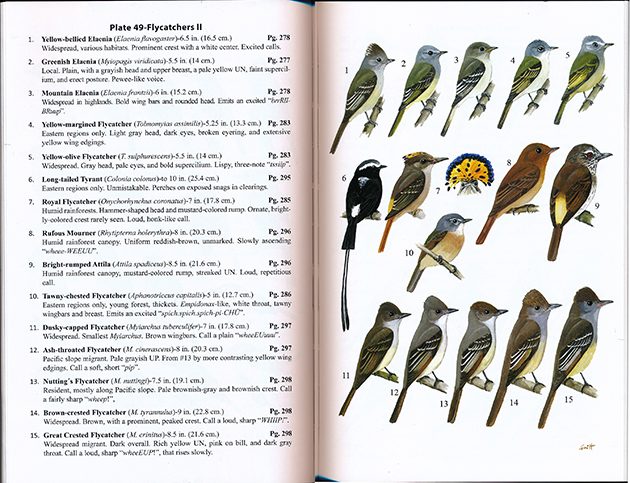

Three artists created the plates, and the distribution is a little uneven, most probably reflecting John Sill’s status as the artist originally announced for the guide. Sill has illustrated 44 plates–herons, shorebirds, pigeons and doves, raptors, swifts, and hummingbirds, woodpeckers, cotingas & manakins, and jays & crows. Michael DiGiorgio does kingfishers & puffbirds, tityras & allies, vireos, and the last 18 plates, which include swallows, wrens, wood warblers, tanagers, cardinals, sparrows, and blackbirds. And Ian Griffiths, though with the smallest number of plates, arguably had the biggest challenge with the illustration of ovenbirds, woodcreepers, antbirds, and flycatchers.

Each plate is accompanied by a page identifying the image by common and scientific name, measurements, and a 1-2 line description of distinctive plumage features, status as migrant or resident, habitat, and vocalization. This theoretically allows the birder to use the plates in the field, apart from the rest of the guide, if you are the kind of person who likes to rip books apart or, probably the better alternative, scan them and add the scans to your smartphone or digital tablet. The images don’t always follow the order of the species in the text section, but each image is meticulously referenced to the longer species account and vice versa.

What about the quality of the images? I think they are all lovely in and of themselves and of excellent field guide quality, meaning each species is differentiated from others by careful detailed work, and the images are presented on the page in a way that enables the birder to compare similar species by size, shape, and plumage. The work of each artist is unique; you can tell which artist did which plate without looking at the signature. Sill’s watercolor images are particularly noteworthy, with their delicately detailed depiction of plumage shades and patterns; his nightjars (above) are a joy. Though a popular bird artist, with many children’s books and calendars to his credit, I think this is his first bird identification guide.

The colors are a bit askew on certain images. Griffith’s Northern Bentbill, for example, lacks the yellow of what should be a greenish-yellow upperside, and a grayish-yellow breast, and the rest of the underside is such a pale yellow it takes an effort to see it. (To be fair, images of this bird vary in color in every bird guide I have, which makes me wonder about variability in the species itself.) And the reds and yellows on the Orioles plate are too pale; these are colors that should jump out at you. Most of the images for all three artists, however, are strikingly colored and subtlety shaded where they should be. My main issue with the artwork is that I’d like more of it–more flight images, more immature images for breeding birds, more close-ups of wonderful details, like the crown of the Royal Flycatcher.

Flycatchers II by Ian Griffiths

Conclusion

The main “competitor” to Guide to the Birds of Honduras is the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of Northern Central America, by Jesse Fagan and Oliver Komar, with illustrations by Robert Dean and Peter Burke, which came out in 2016. (I put competitor in quotes because, in my opinion, you can never have too many field guides, especially for a country that four years ago had none.) They are both excellent guides. Guide to the Birds of Honduras of course has the advantage of focusing on Honduras, while the Peterson guide covers four countries. The Peterson guide is compact and light, a true field guide. The Honduras guide is larger and heavier, you can carry it in your car, I would hesitate to carry it in my backpack. But, the Honduras guide has that section about where to find birds in Honduras and material on Honduran ecosystems, needed information if you are planning your own trip with a local guide or birding on your own.

It’s not quite an apples and oranges choice, but it is a choice that should be made based on your individual birding needs and goals. In the best of all worlds, you’ll be able to purchase both books. Guide to the Birds of Honduras has come down considerably in price, though it’s still the more expensive choice. This is a consequence of self-publishing, the economics of quality, always an issue in the publication of field guides, are even more stark when you are doing all the work yourself.

Would you be able to write and publish your own field guide? This was the question that was running through my head as I sat down to review Guide to the Birds of Honduras. Just think about writing all those species accounts! And, creating all those range maps! I was relieved and happy to discover that Robert J. Gallardo has created, with the help of his artists and colleagues around the world, a professional, comprehensive identification guide, enriched by his years of experience birding the country. I hope that his dream, of utilizing the book, in both English and Spanish, to educate people in and out of Honduras about the richness of the country, to encourage conservation from people and government, comes true.

Guide to the Birds of Honduras

by Robert J. Gallardo; illustrated by John Sill, Michael DiGiorgio, and Ian Griffiths.

Self-published, 2015, 554 pages, 11 plates with 33 color photos, 73 plates with 1000 color illustrations; b/w distribution maps, 1 fold-out color map.

Flexi-binding; 6.5 x 1.4 x 9.4 inches.

ISBN-10: 9992649968; ISBN-13: 978-9992649961

$39.95 – $48.95 (check out Buteo Books, NHBS Books, Book Depository)

I take my hat off, impressed by this endeavour, especially the Spanish version to teach the locals and ensure the future of nature protection in the country