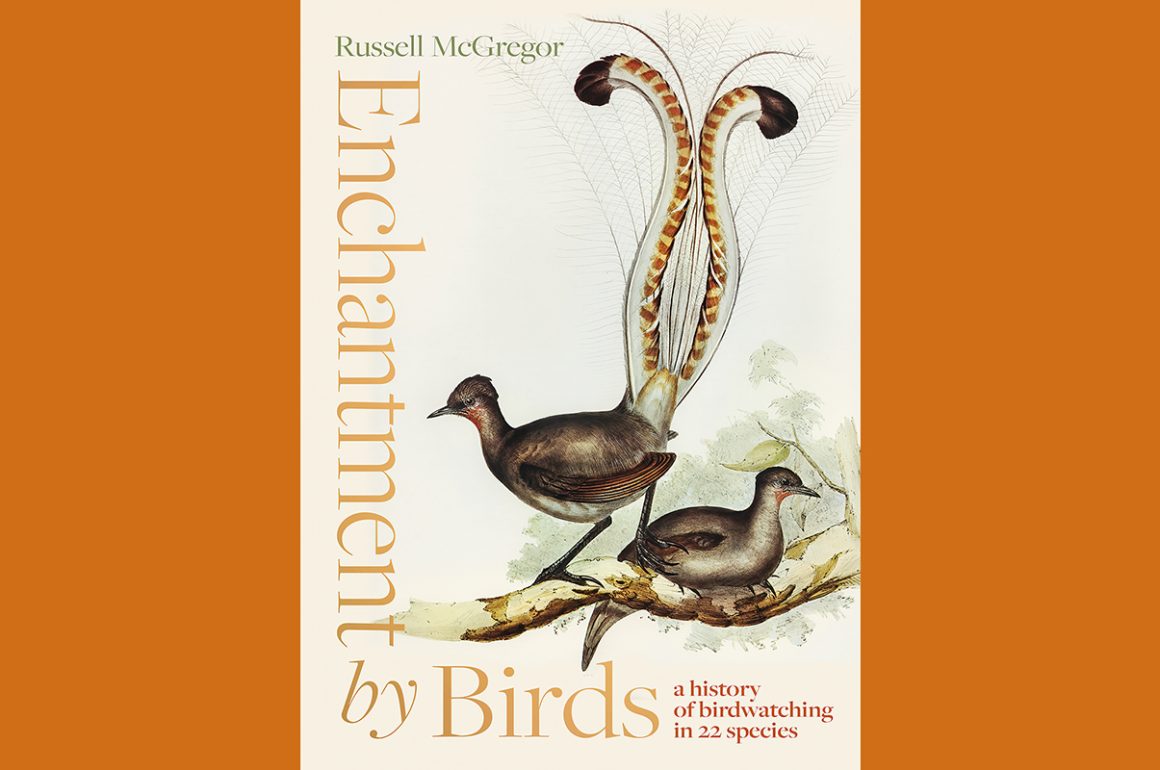

We are birders, so we talk and write and study birds. Sometimes, not too often, we talk and write and study ourselves, our tribe of birders who have grown in numbers, often surprising numbers, around the world Our weddings even make the New York Times!. Books about the history of birding and birders have taken on diverse forms. There are some really good biographies, memoirs, a few traditional histories, an excellent reference book (my favorite Birds and People by Mark Cocker, 2013), and some innovative books that explore the history of birding through art and personal journeys (Kenn Kaufman’s wonderful The Birds that Audubon Missed (2024)) and through objects (the entertaining A History of Birdwatching in 100 Objects by David Callahan (2014), which focuses on birding in Great Britain). In Enchantment by Birds: A History of Australian Birdwatching in 22 Species, Russell McGregor, Australian birder and historian, has chosen a nontraditional way of writing the history of Australian birding. He uses 22 Australian species as entryways to personal yet scholarly discussions of the origins, trends, people, controversies, ethics, and joys of birding in Australia. These bird species (and one subspecies) range from iconic (Laughing Kookaburra) to common (Galah) to intriguing (Tooth-billed Bowerbird) to extinct (Paradise Parrot) to urban magical (Superb Fairywren), but it’s not really about the birds. At least not directly. It’s about what the birds mean to the people of Australia, and often the world, and how important it is to give in to their enchantment.

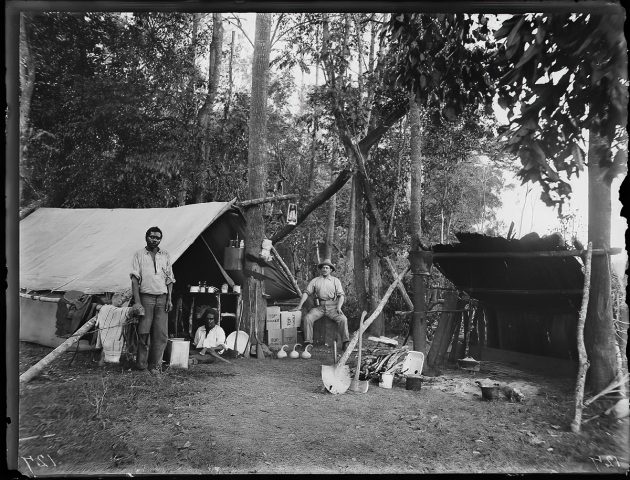

© 2022, McGregor. One of the many black-and-white illustrations McGregor incorporated into his text. It appears in “Tooth-billed Bowerbird: Collecting,” which focuses on the collecting practices of oologist, nest, and skin collector Sid Jackson. The photo is credited to the National Library of Australia, PIC ALBUM 1243/3 #PIC P887/1360-1404; I was able to screenshot it from an open copyright article McGregor wrote about Jackson: McGregor R. 2022. An oologist at Tinaroo: Sid Jackson’s 1908 expedition to north Queensland. North Queensland Naturalist 52: 19-33.

The 21 chapters (plus a bird-named Preface) are discursive essays that explore specific facets of Australian birding from the late 19th-century to roughly the present: the transition from shooting birds with a gun to shooting them with a camera; the development of Australian field guides; bird naming conventions and controversies; birds lost, birds refound, birds saved; aesthetic appreciation of birds through song and behavior; the ways in which birding creates human community. The birds bearing the chapter names are sometimes discussed in detail, but more often serve as gateways to these histories. As McGregor himself comments in the Preface, “most [chapters] emulate the opportunistic practices of birders themselves, chasing new species and themes whenever they come into view” (p. 9). The thematic approach downplays biography, and though we learn about many early egg and skin collectors, pioneering photographers, field guide authors, finders of almost-extinct birds, and RAOU bigwigs (RAOU is the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union), usually it is as actors in the overall historical drama. Only Keith Hindwood, a prolific writer and widely acknowledged expert in all things ornithological, but without the degree that would have accorded him scholarly inclusion, gets his own biographical chapter in the aptly titled chapter Rock Warbler: Belonging. (Hindwood’s first article and favorite bird was the Rock Warbler; the chapter’s theme is the shift to professionalism, but McGregor’s clear admiration for Hindwood takes precedence over thematic generalizations).

A good example of the twists and turns McGregor takes in pursuit of a theme can be seen in Chapter Four–Crested Tern: Photography. The chapter begins with a poetic appreciation of the Crested Tern, one of Australia’s most common seabirds, describing the beauty of the bird and its tousled crest, its mating practices, then a vision of thousands of Crested Terns nesting together near the water. Transition to photography, because a photograph of nesting Crested Terns turns out to be the first photograph of Australian birds (where birds, not nests or eggs were the subject) taken in Australia. The image was taken by A.J. Campbell in 1889 on Direction Islet, off Rottnest Island, near Perth. Side note that Campbell’s son claims the first photograph was of an Osprey, also by his father. A quote by Campbell on how he took the photo, followed by a history of Campbell’s career as a collector of nests and eggs and the author of the Australian landmark book Nests and Eggs of Australian Birds (1900), leading to a detailed discussion of the ethics of egg collecting (which was often accomplished by shooting birds as well as robbing nests), leading to a discussion of collectors who cooked and ate the eggs they collected, leading to a discussion birders who also hunted. Which segueways into the larger historical shift from shooting birds for study to photographing them, a development that McGregor talks about in several chapters. Here, his interest is in the parallels between hunting birds with a gun and photographing them—-both actions use the verb “shoot,” involve the ‘thrill of the chase,’ and reward the birders with a trophy. It’s a fascinatingly structured chapter. We have started with a Crested Tern and somehow gotten into historical socio-psychological aspects of documenting birds, and all the time it feels like we’re reading a good story.

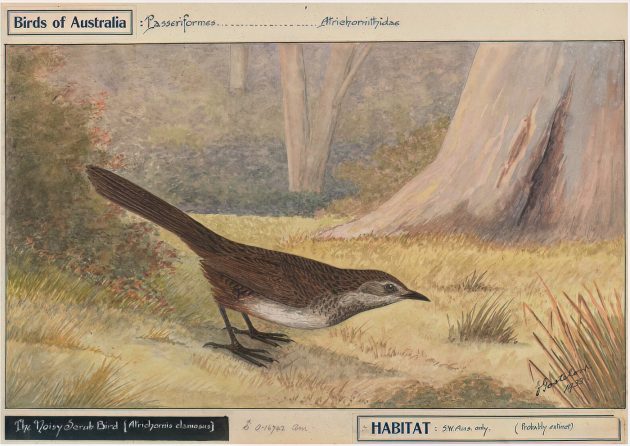

This 1933 painting of the Noisy Scrub-bird by Ebenezer Gostelow is one of the illustrations included in the central color illustration section; McGregor points out that the bird is described as “probably extinct” in the lower right-hand corner. © National Library of Australia.

Other chapters are more focused. “Chapter Three, Tooth-billed Bowerbird: Collecting” concentrates on ornithological collector Sid Jackson’s 1908 expedition to collect the eggs and nests of the Tooth-billed Bowerbird in the Atherton Tablelands. Using Jackson’s field diaries and notebooks, McGregor gives a detailed picture of Jackson’s adventures, which involved advanced tree climbing, collecting as many eggs as possible, and utilizing the talents of three Aboriginal assistants (see photograph at beginning of this review). “Chapter Eight, Paradise Parrot: Tragedy” is all about the unsuccessful fight to save the Paradise Parrot, collected by John Gilbert for John Gould in 1844, assumed extinct in the early 1900’s, then found and identified in 1921 by a young grazier on his Gayndah, Queensland farm, who built a hide and photographed it at its nest in a termite mound. Sadly, the nest failed, and though individual parrots were seen in the area up to 1929, and in another area in the 1930’s, the birding/ornithological community lacked tools and policies for saving the species.

The following chapter, “Noisy Scrub-bird: Hope” relates a happier episode about a skulky bird I actually saw last year in Arpenteur Nature Preserve, Western Australia. I had no idea Noisy Scrub-bird was once considered extinct and rediscovered in 1961–or maybe 1942, since apparently there was some controversy on who saw the bird first and when and who should get credit. I thinks it’s interesting that McGregor decided to make Noisy Scrub-bird the subject of his “Hope” chapter and not Night Parrot, a bird also rediscovered under dramatic, controversial circumstances. Fortunately, by 1966 we had some basis for cooperative efforts that prevented real estate development and created protected habitat for the Noisy Scrub-bird; by the 21st-century, there was no question that protective conservation measures would be taken for the Night Parrot, including involvement of the Ngururrpa people, managers of the Ngururrpa Indigenous Protected Area in the Great Sandy Desert of Western Australia, location of the largest population of Night Parrot (a whopping 40 to 50 birds).

A plate from Neville W. Cayley’s illustrations in What Bird is That? (1931), reproduced in the photograph section. McGregor comments that “Cayley’s illustrations are more artistically accomplished than Leach’s, but his plates are crowded and each image is tiny. © National Library of Australia.

Two chapters, “Laughing Kookaburra: Identifying” and “Collared Sparrowhawk: Innovating” address the development of Australian field guides, a topic also covered in several scholarly articles McGregor published prior to Enchanted by Birds. As a field guide enthusiast and an admirer of Australia’s current surfeit of excellent field guides, I enjoyed reading the detailed comparisons of the two earliest guides, John Leach’s 1911 An Australian bird Book: A Pocket Book for Field Use and Neville Cayley’s 1931 What Bird is That? (with a Laughing Kookaburra on the cover) and about later efforts to produce a field guide for Australia in the mode of Roger Tory Peterson, who almost became an Australian field guide author himself. McGregor spends a lot of time, especially in the “Kookaburra” chapter comparing artwork, placement of birds on plates, taxonomic order, and natural history content and, as a reviewer of field guides, I love that. More importantly, he recognizes that field guides are more than tools for identification, they are gateways to a wider world view of nature. This is always on McGregor’s mind, in every chapter. How do these things and these people motivate us to wonder at and be involved with birds and the wild?

These are some examples of the histories presented in Enchanted by Birds. The book is not meant to be a comprehensive history, but rather deep slices of history interpreted through McGregor’s analytical, often kind vision. Like a good scholar, he defines the parameters of his work in the Preface, named for the critically endangered subspecies, Capricorn Yellow Chat. (This is the only chapter named for a subspecies, understandable since McGregor’s great-great-grandfather, John McGregor, found and shot the first specimen in 1859; its scientific name is Epthianura crocea macgregori). If you’re wondering, like I originally did, why there are no chapters on the Goulds or Australia’s indigenous people, it’s because this is a book about birdwatching as a recreational passion. It starts in the last decade of the 19th century, when the Victorian era’s fascination with the natural world, usually expressed through collections, turned into outdoor observation. The book ends roughly in this century, though McGregor does not get into developments such as eBird or the incredible technology we have now for tracking birds along migration routes. Aboriginal people are part of some of the mini-histories. There are Sid Jackson’s three Yidinji assistants, credited with much of the expedition work and whose photographs McGregor features. He also points out again and again how a species’ numbers have dropped because colonists changed Aboriginal tribes’ environmental practices. In the chapter on the Golden-shouldered Parrot, a bird on the brink of extinction, we learn that researchers have finally realized the importance of the Aboriginal tribes’ environmental stewardship; the 2022 recovery plan for the species depends on the participation, knowledge, and expertise of the Olkola People.

© Vince Lee; portrait of author Russell McGregor

McGregor has written about Aboriginal people, one of his six previous books is Indifferent Inclusion: Aboriginal people and the Australian Nation, which won the 2012 New South Wales Premier’s Prize for Australian History. A retired professor of history at James Cook University, where he taught modern world history, Australian history and historiographic theory, McGregor is also a lifelong birder. It’s clear from looking at his university bio that in recent years he’s been able to combine career and avian passion, writing more about birds and the history of birding, less about environmental history, Aboriginal policy, and Australian nationalism. His previous book, Idling in Green Places: A Life of Alec Chisholm (2020), is a biography of a journalist and naturalist who also figures prominently in Enchanted by Birds. He has also written a number of scholarly articles on topics covered in this book–“An Oologist at Tinaroo: Sid Jackson’s 1908 Expedition to North Queensland,” North Queensland Naturalist, 2022, vol. 52, pp. 19-33; “Alec Chisholm and the extinction of the Paradise Parrot,” Historical Records of Australian Science, 2021, vol. 52, issue 2; “J. A. Leach’s Australian Bird Book: at the interface of science and recreation,” 2022, Australian Field Ornithology, 39 :125-138; “Before Slater: A History of Field Guides to Australian Birds to 1970,” Australian Field Ornithology 2022, vol. 39, pp. 125–138, http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo39125138; “Roger Tory Peterson Down Under: an American’s Influence on Australian Birding Field Guides,” Historical Records of Australian Science, 2025, vol 36, issue 1.

I enjoyed reading these articles, which are more scholarly in tone, heavily footnoted, and full of photographs (surprising for academic articles). You can see the work McGregor did translating them into popular history, making them more into stories and less a recounting of research. The material in Enchanted by Birds is documented by notes in the back, as all good popular histories should be, organized by chapter, giving sources and occasional notes. There is no bibliography nor list of recommended readings, which I missed. It was often hard to trace the repeated sources in the Notes, I spent a lot of time tracing an author’s last name through pages of listings. The index, which includes people names bird names, and topics, was very helpful.

There are illustrations, 22 black-and-white photographs in text and 16 pages of colored reproductions of paintings and field guide plates in a mid-section. The reproductions of the black-and-white photographs have lost much of their sharpness (the Sid Jackson photo above was taken from McGregor’s article, not the book), but they still serve to give us some idea of what the people and events of the time looked like (and to be fair, some, like the Paradise Parrot photographs taken by grazier Cyrril Jerrard were probably not that sharp to begin with). The color photographs are splendid. They feature paintings of parrots by William Cooper and Ebenezer Gostelow, plates from early and more recent field guides, Peter Slater’s paintings of fairy-wrens for his eponymous field guide, a photograph of Roger Tory Peterson with a Rainbow Lorikeet on his head (hey! he’s posing just like us!) and photographs of birds by the author, Graham Pizzey, Raoul Slater, and others, simply illustrating the beauty of birds. In a publishing world where many recently published books have little to no illustrations, it’s good to SEE the birds.

Enchantment by Birds: A History of Australian Birdwatching in 22 Species by Russell McGregor is an appealing look at how birding grew in Australia, with special attention paid to the ethics of collecting eggs and skins, early photography, naming of birds, development of field guides, and the failures and successes of efforts to save endangered species. There are other topics covered–protecting egrets from the millinery trade, introduced birds, birding holidays, feeding birds (frowned and even illegal in some parts of Australia)–but you get the impression that these are the topics that McGregor are passionate about. And the beauty of birds. There are times when the balance between historical details and thematic analysis are a little uneven, but for the most part (like 90%) this is a highly readable book that I think birders with a deep interest in Australia would enjoy reading. It’s also an intriguing model for relating history, and I would love to see a similar book about North American birding history. What birds would represent our significant events and trends? And what bird would represent the beauty of our everyday birds? McGregor offers the Galah, a delicately pink, common bird as representative of the enchantment in nature people overlook every day. And the White-throated Gerygone, a small bird, as representative of the melodic bird song we often ignore. His hope, beyond the field guides and collecting and controversies, is that reading this book will help us see and hear that enchantment. Maybe an Oriole?

Enchantment by Birds: A History of Australian Birdwatching in 22 Species

by Russell McGregor

Paperback: Scribe US, April 1, 2025, $22.00; also Scribe UK, Scribe AU; also available in digital formats

320 pp., illus.

ISBN-10 : 1957363975; ISBN-13 : 978-1957363974; 5.3 x 1.1 x 8.4 inches

Leave a Comment