Birders know that the pairing of farms and birds represents more than mere bucolic romance – it’s a match borne out of a real avian dependence on these man-made landscapes. For many grassland species, our vast expanses of tilled and plowed fields, orchards and vineyards, pastures and rangeland offer an abundance of convenient food and shelter – and some bolder birds even wander indoors to find these things in our barns and stables. Even the names we give to some birds reflect their dependence on the cultivated landscape – we have Barn Owls (Tyto alba) and Barn Swallows (Hirundo rustica) over much of the world, and Orchard Orioles (Icterus spurius) in the Americas really do have a fondness for fruit groves. And of course, there are Cattle Egrets (Bubulcus ibis) and several species of cowbirds that rarely stray too far from livestock.

For most of history, beer has thrived in agrarian settings, too. These days, the trendy “farm-to-glass” label advertises the promise of locally cultivated grans and hops in your beer, but this is hardly a novel arrangement of brewing markets and production. Beer has always been closely tied to farming – whether by the irrigated fields of the ancient Nile, in the private brewhouses of eighteenth-century English manors, or with the rye-and-juniper-flavored sahti brewed in Finnish farmhouses to this day. In fact, it wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution that brewing became a decidedly urban endeavor, as beer barons – particularly in Britain and America – amassed the means of production and harnessed cheap labor in booming cities, using raw materials hauled in from the distant countryside by modern conveyances such as the canal boat or railcar.

Still, the romantic notion of beery terroir remains persuasive and in some corners of Europe, rustic beer styles persist, despite the homogenizing effects of – or perhaps in reaction against – modern industry. Belgium is – quite justifiably – the most famous bastion of such relict preindustrial beers, home to some beers with truly ancient lineages, as well as more modern formulations that proudly incorporate old techniques and ingredients that would seem hopelessly obsolete anywhere else.

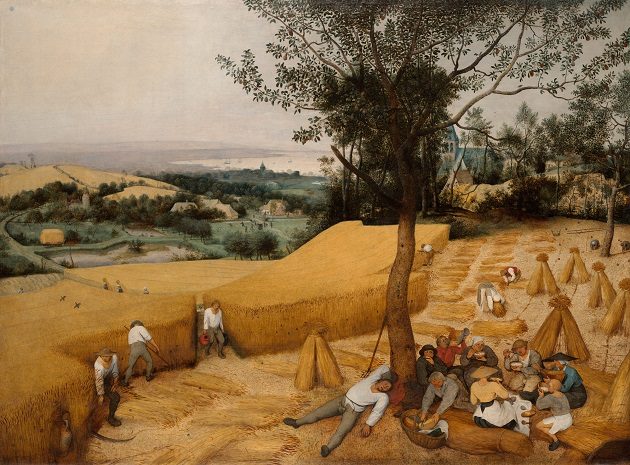

The sobriquet “farmhouse ale” is often applied to two of these beer styles of the Low Countries: in Belgium, to the rustic saison of francophone Wallonia and to the bière de garde made just over the border in French Flanders. Saison and bière de garde have their long-lost origins in the rustic ales of the Brueghelian countryside and the handful of farmhouse breweries that produce them are often a curious blend of modern production and quaint vestiges of old brewing traditions. At least one Belgian saison brewery continues to use steam-powered equipment – the aptly named Brasserie à Vapeur in Pipaix, which remains, for all intents and purposes, a working museum of antiquated brewing equipment. And both saison and bière de garde are often packaged in corked Champagne-style bottles generally reserved elsewhere in Europe for wines and lovingly wrapped in decorative tissue paper, adding a touch of handmade reverence to these old-fashioned products.

Historically, saison was a beer tied to time as much as it was to place. It was originally made during what was once the traditional brewing season in Europe in the days before modern refrigeration, generally October through April, when the threat of spoilage was diminished thanks to the cooler weather. Once brewed, saison would be laid down for use during the hot summer months, when a farming household would be much too occupied with fieldwork for making beer. For centuries, saison – which literally means “season” in French – was served to seasonal farmhands known as saisonniers, who drank copious amounts of it not as a reward at the end of the day, but as a thirst-quenching restorative throughout the day – in prudent lower-strength versions, of course.

In Flanders Fields: seasonal farmhands take a well-earned break to enjoy an al fresco farmhouse ale in The Harvesters by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Note the two birds flying over the wheatfield on the lefthand side.

By the early twentieth century, however, saison was sliding into obscurity. Its glory days as a farmhouse beer were well behind it, and as mechanized modern agriculture diminished the need for seasonal laborers, so too ebbed the demand for the venerable ale that had slaked the thirst of their forebears for centuries. Changing tastes in beer, now leaning towards more modern flavors imported from Britain and Germany – as well as the privations of two world wars – only seemed to seal the fate of saison. In the postwar years, the style was hanging on as an arcane regional specialty, brewed by an ever-shrinking number of small producers. But in the 1980s, the pioneering American company Vanberg & DeWulf began exporting a stronger Belgian saison named Saison Vielle Provision by Brasserie Dupont, a brewery operating in a 1759 farmhouse in Tourpes. Now better known as Saison Dupont, this 6.5% alcohol-by-volume beer soon became the international standard for this heretofore little-known style, now considered a world classic and much copied by homebrewers and craft brewers alike.

So, while the improbable resurgence and international popularity of saison provided a happy ending in the story of farmhouse ales and farming, ongoing changes in agricultural practices are creating an uncertain future for grassland birds. The alarming decline of grassland species like the Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda) and Eastern Meadowlark (Sturnella magna) has been the most precipitous and extensive of any group of North American birds, and much of this decline results from changes in agricultural land management. Grassland birds continue to lose habitat as small, family-run farms are replaced by large-scale, corporate agriculture interests, or are bought up and consigned to real estate development. And where farms do remain, more intensive agricultural practices – including early and more frequent summer mowing and an increasing reliance of ecologically bankrupt monoculture farming – are making what little farmland remains less attractive to nesting grassland birds.

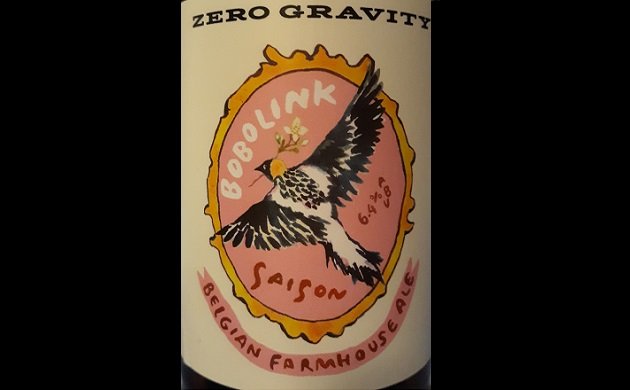

It’s true that grassland bird conservation can often seem at odds with farming and it doesn’t help that some birds are viewed as agricultural pests. But efforts like The Bobolink Odyssey, a project run by the Perlut Lab of the University of New England in Biddeford, Maine, are attempting to bridge that divide by investigating land management practices in Vermont that balance the needs of both farmers and grassland birds. And to further underscore the link between healthy farmlands, farmhouse beer, and grassland birds, Zero Gravity Craft Brewery of Burlington, Vermont, has brewed a Bobolink Saison to support The Bobolink Odyssey. Bobolink Saison is a farmhouse-style ale with a true farm country bird for a mascot, that iconic grassland blackbird with an unforgettable song and a slightly silly name: the Bobolink (Dolichonyx oryzivorus).

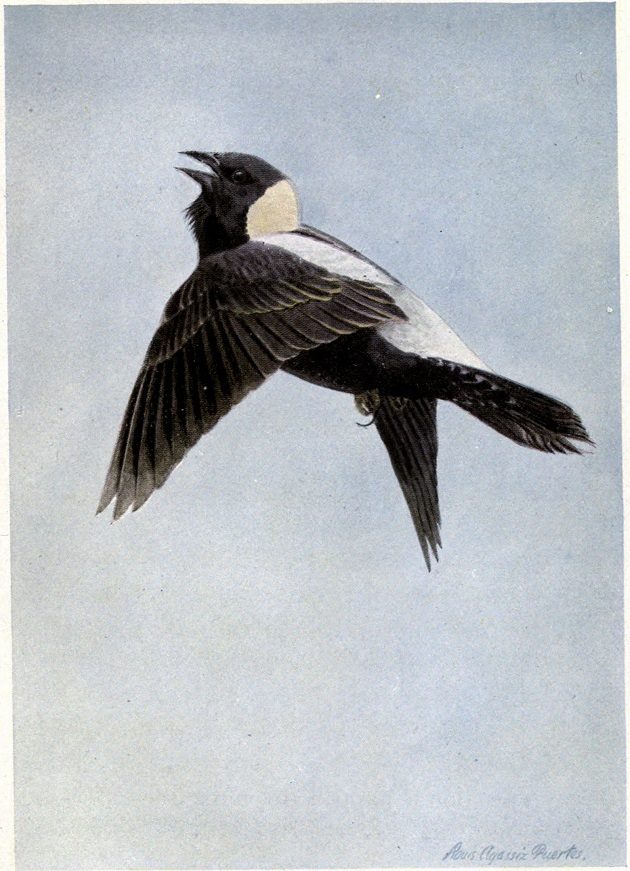

“Bubbling Bob the Bobolink”, as illustrated by Louis Agassiz Fuertes for The Burgess Bird Book for Children (1919).

Zero Gravity brews Bobolink Saison with organic malt and jasmine rice, the latter being a sly nod to one of the many old folk nicknames for the Bobolink – “ricebird”, given for the blackbird’s fondness for feeding on cultivated grains on their annual autumn journey to South America. In fact, the specific epithet oryzivorus means “rice-eating” in Latin. The Bobolink’s noted predilection for the grain has earned it the ire of rice farmers from South Carolina’s Lowcountry to Argentina, and undoubtedly – in older times, we hope – this perceived thievery was avenged with shotguns and birdshot. Bobolinks have even been killed for the dinner table: an 1859 edition of The Spirit of the Times – an American weekly newspaper geared toward sportsmen – recommended cooking rice-fattened Bobolinks with rice in a pie.

Of course, at Birds and Booze we advise limiting one’s ingestion of “Bobolinks” to this excellent saison. Zero Gravity’s take on the Belgian style hits all the right notes – bright, delicate, and refreshing, full of assertively fruity flavors but still dry and clean. Bobolink Saison is a dark, hazy goldenrod, a color not unlike the buffy backside of a Bobolink’s head, capped with a dense, off-white foam. The nose is lemony and floral, followed by a good dose of grassy hay, white pepper, and coriander, then sweet, bready malt with a suggestion of fragrant jasmine rice. The palate is imbued with a tart fruitiness, laced with white currant and lemon peel mixed with sweet cereal and spicy and flowery hints of Northdown hops. All that rice in the grain bill – the Bobolinks must have left some for the brewers! – keeps things crisp and drinkable and Bobolink Saison ends on a pleasantly dry and earthy note.

Good birding and happy drinking!

Zero Gravity Brewing Company: Bobolink Saison

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Four out of five feathers (Excellent).

Leave a Comment