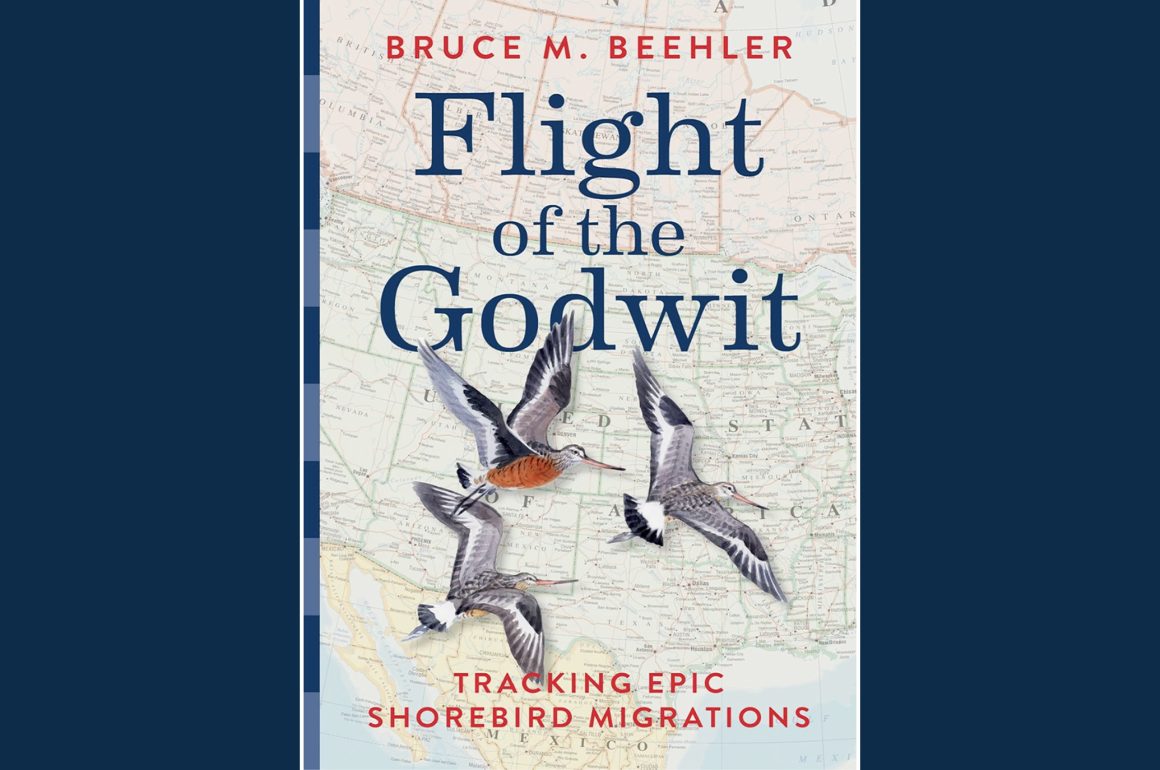

Have you seen the Magnificent Seven? No, I don’t mean the 1960 Western film or its three sequels or Japanese predecessor, I mean the amazing group of shorebirds dubbed “magnificent” by ornithologist Bruce M. Beehler in his latest book, Flight of the Godwit: Tracking Epic Shorebird Migrations. Part natural history, part travelogue, Flight of the Godwit tracks Beehler’s observations of North America’s largest, most charismatic shorebirds as he travels across the U.S. and Canada to their breeding grounds on several trips, most made during the Covid years. His main focus are seven shorebirds–Hudsonian Godwit, Bar-tailed Godwit, Marbled Godwit, Whimbrel, Long-billed Curlew, Bristle-thighed Curlew, Upland Sandpiper. And of these, his specific focus is the Hudsonian Godwit, a super-migrator with a route that traverses eastern and central North America, one of our largest, most striking shorebirds but frustratingly elusive.

This focus on the Magnificent Seven doesn’t stop Beehler from observing and commenting on smaller shorebird species. But be aware, the term “shorebird” is used in a very specific sense, which he explains in the Introduction: “When discussing “the shorebirds,” I am referring to the family Scolopacidae–the sandpipers and their close relatives, but excluding the plover, stilts, avocets, and oystercatchers….this bird family (to the exclusion of the others mentioned) encompasses the great global migrators. Their incredible travels are what inspires me and what I would like to present to the reader” (pp. 6-7). Plovers are my favorite group of shorebird, and the other three excluded groups are close seconds, so I was initially disappointed I wouldn’t be reading about them. However, there are an awful lot of intriguing species left to ponder, 35 to be exact, listed on a Featured Shorebird page. They range from the common Sanderling to the western Surfbird to the endangered Red Knot to grasspipers like Buff-breasted Sandpiper to the whirling Wilson’s, Red-necked and Red Phalaropes to the extinct Eskimo Curlew, a bird I think Beehler would add to his Magnificent List if he could (making it the Magnificent Eight). This doesn’t mean plovers, avocets, stilts, and oystercatchers are totally absent from the book, they show up in Beehler’s counts of birds he sees on the road and at the godwit breeding grounds and in the first section’s natural history narrative. But they don’t enter Beehler’s ruminations on migration and habitat as he travels across the country, and they aren’t the subject of the bits of natural history background and scientific findings sprinkled throughout the narrative.

©2024 Bruce M. Beehler & @2024 Alan Messer/Janet Messer; An adult Whimbrel in an East Coast Salt Hay marshland, possibly similar to what author Bruce Beehler saw in Maine in 1969,

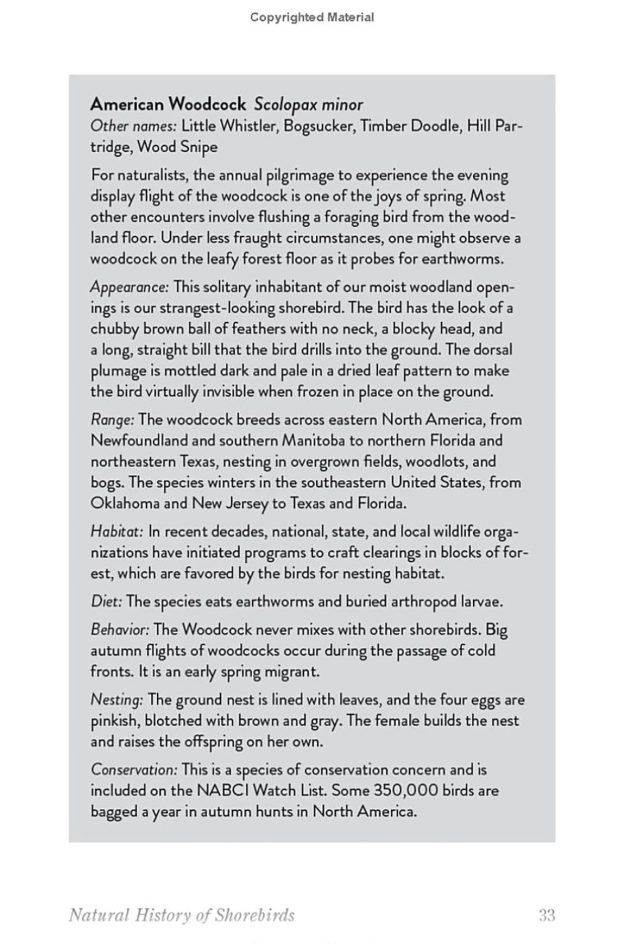

Flight of the Godwit is divided into three main sections. Part I is an introduction, with chapters on Beehler’s personal history with shorebirds, highlighting his first magical sighting of a Whimbrel in Hancock, Maine in 1969, and a general natural history of the shorebird order. Part II is the travelogue section, the heart of the book, offering Beehler’s first-person narrative of his road trips to the breeding sites of the Hudsonian Godwit in Canada, Alaska, and the edge of the Arctic. Part III is about closure, descriptions of where shorebirds winter, including Florida, and a summary of Beehler’s travels and his thoughts on conservation and the future of shorebirds. Sandwiching these sections are two extremely helpful chapters in the front of the book on How to Read This Book and the Introduction, and the expected back-of-book chapters: Epilogue, Acknowledgments, Bibliography, and Index. Species-specific information boxes are interspersed throughout narrative, 29 in all, profiles of each of the 35 focused species (some are grouped together).

As a birder who loves road tripping from New York City to southeast Florida, stopping at birdy and promising new natural places along the way, I read Beehler’s travel narratives with delight, empathy, and occasionally amazement. He really did a LOT of driving! When necessary to get to remote places up north, he employed other travel modalities. Beehler sums up his travels in his Introduction:

“Between spring 2019 and spring 2023, I made 13 road trips in search of shorebirds. I logged 223 road days, traveling by car 35,087 miles, by airplane 14,614 miles (plus two helicopter charters), and by train 378 miles. I spent 108 days tent camping while traversing 37 states and 9 Canadian provinces and territories. I visited the breeding grounds of all three North American godwits, all the Magnificent Seven, and the important autumnal staging site of the Hudsonian Godwit on the western shore of James Bay in Canada.” (p. 5)

Unlike Beehler, I prefer to sleep in inexpensive motels on the road (yeah, I’m a wuss), but I share his love of traveling solo, the freedom to stop and explore where and when I wish, the privilege of being open to serendipitous sightings, meetings, adventures small and large. Of course, when Beehler sights a migrating Hudsonian Godwit in the middle of a flooded field on private land in Oklahoma, his thoughts go to the unexpectedness of the sighting (why here and not in a federal reserve or state park?), the habitat preferences of godwits migrating north, the presence of Franklin’s Gulls and the possibility that they may be a convenient marker for spotting the godwits across distances, and the foraging style of the godwits compared to other types of shorebird foraging. Me, I just want the photo. (Beehler wants the photo too, but he’s obviously thinking of much more than aperture width when he takes it.) His writing is inspiring and makes me want to go on the road again, soon, and maybe with more than a few good photos and sightings as my goal.

©2024 Bruce M. Beehler; American Woodcock information box[/caption]

©2024 Bruce M. Beehler; American Woodcock information box[/caption]

The road trips are described in eight chapters, some of which combine Beehler’s 13 trips. They take him from Maryland to the lower Rio Grande Valley to Churchill, Manitoba in 2019, following the northward migration route of the Hudsonian Godwit; to the Great Plains in 2019 and 2020, to observe Marbled Godwit, Long-billed Curlew, and Upland Sandpiper on their breeding grounds; to southwest Alaska in mid-May 2021, to spend time with shorebird expert Nathan Senner and his team at Beluga, where they observe and band breeding Hudsonian Godwits; to Yukon, Alaska and the Northwest Territories, to the third breeding grounds of the Hudsonian Godwit in 2022; and, in 2019, to Longridge Point on James Bay, Ontario, a critical shorebird staging site, where he volunteers with a shorebird survey team for 15 days. As you can see, the chapters are not in chronological order, but rather reflecting the birds’ migratory journeys.

All these trips are engaging in their focus on bird life and habitats and the good and unfortunate things that happen when you’re on your own in a country blunted by a pandemic, but it’s the Yukon/Alaska/Northwest Territories that really captured my interest. The journey to the Sub-arctic and Arctic Outposts, as the chapter is titled, is a tale of solo travel to places so isolated and hard to get to that it blows the mind of the turnpike traveler. It takes Beehler first to western Alaska, to visit the breeding grounds of the Bristle-thighed Curlew, Bar-tailed Godwit, and Whimbrel, and then to the Mackenzie delta of the Northwest Territories, in search of Hudsonian Godwits. This was, Beehler writes, “an adventure I had dreamed about for a decade.” He drives from his home in Maryland to Fairbanks, Alaska in eight days, zooming through the Midwest and Prairie Potholes, slowing down his writing slightly when he reaches Alberta, a new province for him, then shifting into quietly joyous prose when he reaches northern British Columbia and enters southern Yukon. He is the only person on the road, encountering Dusky Grouse, Black Bears, Woodland Caribou, herds of Wood Bison, Mule Deer, Dall Sheep, all indifferent to his presence. Traveling on the fabled Alaska Highway, Beehler stops at “a decrepit but friendly diner,” finds an honest car repair shop, and sees his first Moose. From Fairbanks to Anchorage, and then a flight to Nome.

Beehler’s experiences in Nome, then Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow) are good reading, and he does see his target birds, though the Bristle-thighed Curlew is a challenge (not a surprise to anyone who’s birded Alaska), but it’s his drive from Anchorage to the Northwest Territories, specifically the Arctic Ocean of Canada, that fascinated me. After spending the night at Dawson City, the center of the Klondike Gold Rush and now a busy tourist town (his trip preparations include buying Bear-bangers and Bear Shock), Beehler starts driving north-northeast on the Dempster Highway. A 458.3 mile-gravel road* that goes from the Klondike Highway to Inuvik, a town on the Mackenzie River Delta, with a 94-mile extension to Tuktoyaktuk, an Inuvialuit hamlet on the Arctic Ocean (in fact, the only settlement on the Arctic Ocean connected to the rest of Canada by road), the Dempster Highway roughly shadows an old dog sled route. It’s a challenging drive involving two seasonal ferries, a dearth of gas stations (just four along the route); there are no intersections with major roads, wifi only at the few towns along the route. Along the highway, Beehler finds wonderful surprises–Tombstone Territorial Park turns out to be “one of the prettiest wild places in North America–a legitimate competitor with Yosemite, the Tetons, and Denali” (p. 162); a massive Grizzly Bear crosses the road in front of the car and Beehler gets a photo; the parking lot where he spends the night at Tuktoyaktuk becomes the center of an informal, chatty get-together of visitors and Inuvialuit residents. And disappointments–he can’t find a Boreal Owl or Gray Chickadee nor Hudsonian Godwits. It’s a sad scene, here he is at the end of the world, at least the “civilized world,” as far north as he can go, and his major, special target bird is not there. Beehler is impressively honest, writing his fears that he had not planned thoroughly enough, had not contacted the right researchers or organizations. But his good nature ultimately prevails:

“On this trip I drove to the most distant point on the North American continent accessible by road and returned home without a single flat tire, car breakdown, or traffic ticket, having racked up 10,929 miles…. I had spent quality time with the Bristle-thighed Curlew and Bar-tailed Godwit and three species of bears. The achievements had handily topped the disappointments. This was the finest North American solo expedition of my life–one that I recommend to readers with an adventurous bent” p. 174).

If you follow Beehler’s blog, Birds and Nature North America, you may have already read about these travels. Though the places and birds are the same, Beehler has totally rewritten the book narrative to be of one thematic piece. It is also more descriptive since none of his photos of birds, their habitats, people, or landscapes have been transferred over. This is really too bad. Alan Messer’s black-and-white drawings of the birds profiled in the book are very good, but they don’t hold the flavor or immediacy of Beehler’s trip photos, and I encourage readers to check the blog to get some of their flavor. Or watch his February 2024 presentation, “30,000 Miles in Search of Godwits, from the Mexican Border to the Arctic,” to the New York Linnaean Society, available on YouTube (it’s really good, I had the pleasure of watching it in real time).

Beehler’s literary talents encompass both popular science and travel evocation, sometimes combining both. His descriptions of prairies, boreal spruce forests, open tundra, and boggy bogs are defined by the birds he sees and hears and framed by his knowledge of environmental ecosystems. His language is simple, often graceful, and always calm, even when he’s caught in a life-threatening supercell in Great Salt Plains State Park, Oklahoma. There are times when the adventure of the road lulls to a series of camp nights and bird lists, but the pace soon quickens as Beehler spots a Dusky Grouse in the middle of the road, a Polar Bear in the middle of Utqiagvik, or engages in field work on James Bay. I would have liked to have learned more about the people Beehler encountered in his travels and to have “heard” a little more dialog with these locals, fellow travelers, and researchers, but I respect Beehler’s preference for communicating his thoughts as he travels on his own.

Bruce Beehler spent much of his career researching birds and biodiversity in New Guinea, producing groundbreaking research with significant implications for conservation and some of the seminal works on this area: the two-volume Ecology of Indonesia Papua (coauthored with Andrew J. Marshall, 2011 & 2012), The Birds of Paradise: Paradisaeidae (coauthored with Clifford B. Frith, 1998), The Birds of New Guinea, Second Edition (Princeton Field Guides series, coauthored with Thane K. Pratt, 2014), Birds of New Guinea: Distribution, Taxonomy, and Systematics (coauthored with Thane K. Pratt, 2016), plus New Guinea: Nature and Culture of Earth’s Grandest Island (coauthored with Tim Laman, 2020). The American Ornithological Association honored his contributions in 2021 with the Elliot Coues Award. Beehler is currently a research associate with the Birds Division of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institutes, after past stints with the Wildlife Conservation Society, U.S. Department of State, Counterpart International, Conservation International, and the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation. In recent years, Beehler’s talents have turned to writing about personal encounters with birds and migration in North America, first North on the Wing: Travels with the Songbird Migration of Spring (2018), the predecessor for this book, and then Natural Encounters: Biking, Hiking, and Birding Through the Seasons (2019).

Flight of the Godwit: Tracking Epic Shorebird Migrations by Bruce M. Beehler is a lovely addition to our shorebird and bird travel literature. My focus on the travel part has neglected the wealth of scientific information cleverly, almost seamlessly integrated into the text. Beehler writes of super-migratory routes, winter routes, the enigma of young birds knowing these routes, shorebird foraging techniques, nesting strategies, old and new research methods, from banding to solar transmitters to Motus networks, conservation concerns, and more. There is a lot here. But Beehler’s main goal seems to be to share the joy of the birding road, and in that he has masterfully succeeded.

©2022, Donna L. Schulman, Hudsonian Godwit at Mecox Inlet, Southampton, N.Y

* Beehler writes that the Dempster Highway is 478 miles long, mixing up its length in kilometers with its length in miles, an error that will hopefully be corrected in the final book. I read a PDF sent by the publisher.

Flight of the Godwit: Tracking Epic Shorebird Migrations by Bruce M. Beehler; Illustrated by Alan T. Messer Smithsonian Books, distributed by Penguin Random House, 2025

272 pages, 30 illustrations

ISBN-10 : 1588347877; ISBN-13 : 978-1588347879

$27.95 hardcover (less from the usual sources); also available in eBook and audio formats

The migration of the Bar-tailed Godwit subspecies Limosa lapponica baueri across the Pacific Ocean from Alaska to New Zealand is the longest known non-stop flight of any bird. The Hudsonian keeps stopping along the way… Bar-tailed is the true migration king!

thanks for the article and bringing this book to our notice