Indeed, most bird species have eyes that are on the sides of their heads, but the eyes of some bird families face forward. Why the difference?

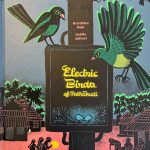

Birds with side-facing eyes have a very broad field of vision – it can reach almost 340 degrees, so there are almost no blind spots. That is particularly important for birds that are more likely to be prey than predators. For example, a pigeon can watch you approach from behind without moving its head. Of course, there is a downside to this as well – there is very limited overlap between the two eyes, which makes it more difficult to judge distances.

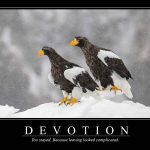

In contrast, many predators have forward-oriented eyes. That gives them excellent binocular vision as there is a substantial overlap in what both eyes see. And binocular vision greatly supports judging distances, something that is important when catching prey. Naturally, the downside is a limited field of view – so if you are very quiet and an owl does not move its head, you should be able to approach it from behind. Owls are actually the family that takes the forward-oriented eyes to extremes, probably because they mostly hunt at night. Under these conditions, depth perception matters much more than scanning a broad horizon compared to daytime raptors, which need to scan a broad area to find prey.

So, in short, it is a tradeoff between two desirable aspects – a broad field of view (side-facing eyes) and good judgement of distance (forward-facing eyes). Generally, which aspect is more important to survive depends on whether a species is more likely to be prey or predator.

Assuming the same logic applies to humans, this means our species is designed more as a predator and less as prey, which (sadly?) sounds about right.

Photos: Orange-breasted Green Pigeon, Bundala NP, Sri Lanka, March 2025; Northern Hawk Owl, Genhe area, Inner Mongolia, China, December 2024.

Leave a Comment