Peter Matthiessen was peripatetic both in his travels and in his interests in flora and fauna of all kinds, including (among all else) reptiles, fish, birds, mammals. The latter form the backdrop for his 1978 tour de force book The Snow Leopard (he had, as well, a long obsession with the Bigfoot/Yeti which, if it exists, must surely be a mammal). The striped sea bass and the Long Island fishermen who seek them are the subject of Matthiessen’s Men’s Lives (1986); and reptiles (sea turtles, that is), play an oversize part in his great novel Far Tortuga (1975).

And he was an avid birder, as well, starting in boyhood when he wore out multiple copies of his Peterson’s field guide. He was denied permission to enroll for an Ornithology class at Yale because he had never studied biology – until he drove to New Haven to convince the registrar, in person, of his birding prowess. (But he was an English major and, except for some college courses, had no formal training as a naturalist.)

Later he published The Shorebirds of North America (1967) and The Birds of Heaven (2001), the latter of which chronicles his search for the world’s fifteen species of cranes.

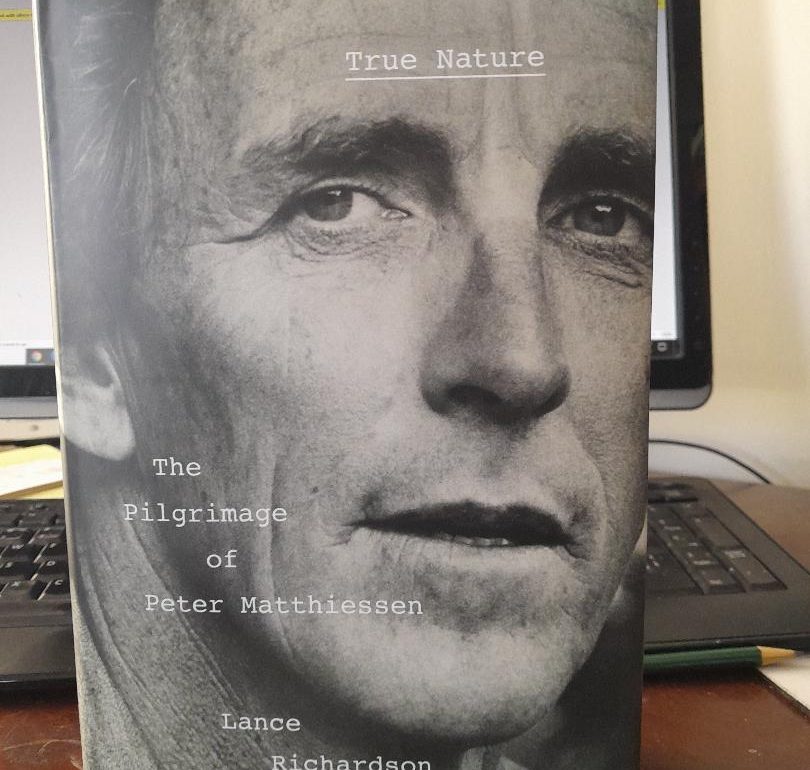

(In other words, that’s why Richardson’s new biography, True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen, merits a review on the 10,000 Birds blogsite.)

Of patrician New York stock, Matthiessen grew up in material comfort but not unalloyed happiness — far from it: “I’ve been angry since I was about eight,” he said. Later in life, one of his groupies, a girl who worshipped him as a hero, said “he was really, probably, the unhappiest man I’ve ever met.”

Six-foot two, charismatic and ruggedly handsome, he was what used to be called a man’s man. And he was quite the ladies’ man, too, for his whole life – a serial adulterer through three marriages.

He was a lousy husband and a lousy father. He left his son Alex at home so he could go on the two-month expedition to Nepal that resulted in The Snow Leopard. Alex was eight years old at the time, and had recently lost his mother, Matthiessen’s second wife Deborah Love, to cancer. She became one of the subjects of The Snow Leopard (along with the snow leopard itself, of course).

One might say, if so inclined, that the English novelist Evelyn Waugh (Brideshead Revisited, etc.) would have been completely unbearable as a human being were it not for his conversion to Roman Catholicism (the joke being that he was pretty unbearable anyway); and something similar could be said about Matthiessen and his adoption of Zen Buddhism as a lifelong pursuit. Another son, Luke, said that Zen helped his father – but it was also “a way of tuning everything else out . . . . a way of him escaping again.”

Matthiessen wrote some thirty or so books, about a third of those fiction and the rest of them non-fictive accounts of his expeditions (all over the place), or social commentaries (he was a supporter of Cesar Chavez of the United Farmworkers’ movement in the nineteen-sixties, until Chavez turned on him; and in the nineteen seventies he went to bat for Leonard Peltier of the American Indian Movement, who was convicted, wrongfully, Matthiessen was convinced, of killing two FBI agents); or environmental rabble-rousing. But he was adamant, throughout his career, about wanting to be known as a novelist, not a nature writer.

Richardson’s research into Matthiessen’s life and career appears impeccable. (Most impressive is that he retraced the same Snow Leopard steps Matthiessen took across the Himalayas to the Crystal Monastery in Nepal – a heroic journey back then, and now.) And he communicates the complexities of his subject well.

You could put all of Matthiessen’s books on one pan of a balance scale, and Far Tortuga, in the other pan, would outweigh them all. I guess it’s my favorite book in all the world. It does not appear on the Modern Library’s list of “One Hundred Best Novels of the Twentieth Century” nor (presumably – I haven’t checked) any other such list. That is inexplicable. It should be in the top eight or ten. Or maybe two, alongside Ulysses.

It’s a story about turtle fishermen in the Cayman Islands, narrated mostly in pidgin dialect and dialogue, infused with atmospherics of West Indian Zen. Birds don’t play much of a part in the book, other than in the very last line: “bird cry and thundering / black beach / a figure alongshore, and white birds towarding” (whatever that means), and which, in context, will hit you like a sledgehammer to the chest – in a good way, I mean.

So that’s the other reason why this new biography of a flawed, tortured, selfish man who wrote a magnificent, sublime, astounding book merits a review on the 10,000 Birds blogsite.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

True Nature: The Pilgrimage of Peter Matthiessen. By Lance Richardson. Pantheon, New York. 709 pp., $40.

Leave a Comment