If you are worried about, or hoping for, a post with an LGBT topic: No, this is about flamingos. And the chemistry behind their color.

Flamingoes get their color from their food, but then also convert some of the relevant substances before depositing them in their feathers.

The reddish-pink color of marine organisms such as freshwater algae, shrimp, lobster, and salmon mainly comes from astaxanthin.

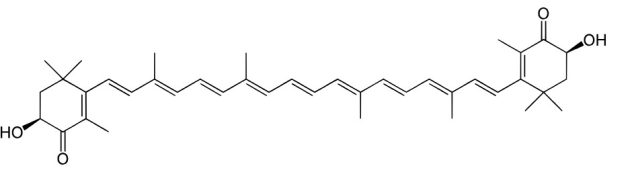

Astaxanthin

Flamingos eat algae and brine shrimp, thus taking up astaxanthin. Then, some of this astaxanthin is converted into a similar molecule, canthaxanthin, in their livers, in a reaction that chemically can be described as a reductive dehydroxylation (the hydroxyl groups at two carbon atoms are converted into hydrogen). This is catalyzed by carotenoid dehydrogenases/oxidases.

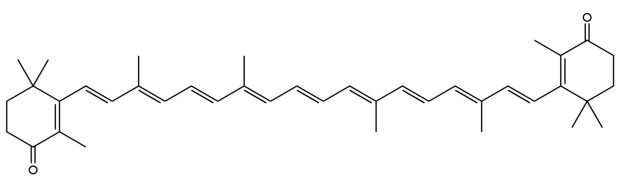

Canthaxanthin

The canthaxanthin is then deposited into the feathers of the flamingos, which is the main contributor to the pink color of most flamingo species.

Here are a few more mildly relevant facts related to flamingos and their colors:

- If you are a flamingo yourself and are looking for a partner, choose one with a strong pink color – this indicates your mate is good at foraging.

- As the color requires the right food (i.e., containing carotenoids), flamingos without access to this food do not have pink feathers. This can happen in zoos (though zookeepers sometimes feed them astaxanthin directly to justify the ticket prices – visitors would be unhappy to just see grey flamingoes).

- Also, I guess that this flamingo seen in Shanghai in the wild in winter did not get many carotenoids in its diet.

Finally, two completely irrelevant facts (aren’t those sometimes the most interesting?):

- Given its importance for flamingos, the University of Bristol named astaxanthin as the “Molecule of the Month” in June 2021. Unfortunately, the acceptance speech was not recorded

- And design company Figma points out that “Flamingo pink is a vibrant, warm hue sitting between pink and orange on the color wheel. This lively shade evokes feelings of playfulness and joy, similar to soft pinks like salmon and blush. Perfect for designs aiming for a cheerful, inviting atmosphere or playful accents in a pastel palette.”

Sources:

In his essay “Red Wings in the Sunset,” featured in the book The Flamingo’s Smile, Gould critiqued the discredited theory of American artist and naturalist Abbott Handerson Thayer (early 1900s).

Gould’s points include:

Thayer’s flawed theory: Thayer, a pioneer in the general principle of countershading for camouflage (which is scientifically sound and used by the military today), argued that all animal coloration served for concealment. He proposed that flamingos were pink to camouflage themselves against the colors of the sunset and sunrise.

Logical fallacy: Gould used Thayer’s flamingo argument as an example of “illogic and unreason” because it ignored basic observations. Flamingos are often seen as dark silhouettes against a bright sky, making them highly visible, not camouflaged.

The actual reason for pink: As Gould explained, the pink coloration is not for camouflage but results from the carotenoid pigments in their diet of crustaceans and algae, which their bodies process.

Scientific lesson: For Gould, the anecdote served as a cautionary tale in science: the need for careful observation and evidence-based reasoning, rather than trying to make all data fit a single, overarching theory.

Some AI search engine got all this together for me (note the utterly boring language), but rest assured: I did read the essay.