If, like me, you grew up in Germany, the word “nectar” (well, Nektar, really, as Germans prefer the more aggressive-sounding k over the soft and suspiciously foreign c) does not have a particularly positive ring to it.

That’s because under German law, fruit juice labelled as Nektar is not pure fruit juice. Seeing “Nektar” on a bottle in Germany legally indicates that it’s not 100% fruit juice—there is a regulated lower limit on the fruit content, while water and up to 20% added sugar may be included as well. No wonder Germans grow up associating nectar with something sugary and cheap.

Birds might agree with the “sugary” part, but definitely not with the “cheap.” Several bird families specialise in feeding on nectar—a perfectly sensible choice, given that simple sugars can be converted into energy quickly and efficiently. And unlike humans, birds have very little risk of becoming overweight in the process.

So: nectar. What is it, how and where is it made, and what does it contain?

Most nectar is a mixture of sucrose, glucose, and fructose, produced by flowering plants as an incentive to attract pollinators—bees, butterflies, birds, and other animals that enable the long-distance sex life plants depend on to reproduce. The exact recipe depends on the plant species and the pollinators it hopes to attract.

For example, flowers visited by hummingbirds tend to offer sucrose-rich nectar, essentially table sugar dissolved in water. Many insect-pollinated plants lean more toward the monosaccharides glucose and fructose.

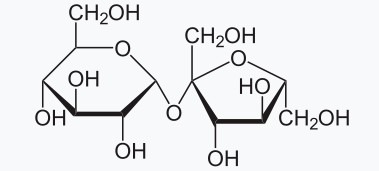

Sucrose is a disaccharide (“two rings”). A chemist who wants to show off might refer to it as ?-D-fructofuranosyl ?-D-glucopyranoside.

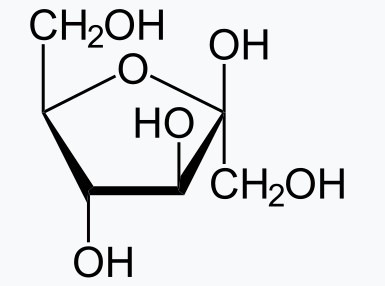

Fructose, a monosaccharide

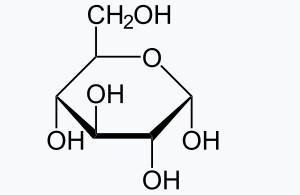

Glucose, a monosaccharide

Hummingbirds are extremely good at digesting sucrose: they split it using the enzyme sucrase, producing glucose and fructose, and then turn those directly into energy—almost immediately after ingestion.

These three sugars form the basis of nectar, but they are not the only ingredients. Nectar may also include:

- Amino acids (nutritional bonuses or chemical signals)

- Alkaloids like caffeine or nicotine

- Minerals such as potassium and calcium

- Secondary metabolites that deter nectar thieves without harming legitimate pollinators

- Antimicrobial proteins called nectarins, which protect nectar from microbial spoilage

The composition shifts depending on the intended pollinators. Bird-pollinated flowers typically produce larger volumes of relatively dilute, sucrose-rich nectar, whereas many bee-pollinated flowers produce less nectar with different sugar balances. Flowers high in alkaloids may be selectively discouraging nectar robbers—animals that drink nectar without pollinating. Some plant families produce nectar with less common sugars – for example, the nectar of many Protea species contains sugars such as xylose, mannose, arabinose, and rhamnose. These sugars likely add specific functions to the nectar, with xylose-rich nectar hypothesised to be more stable, more easily diluted, and less prone to fermentation.

There is also a clear difference between hummingbirds and sunbirds in their nectar preferences. Hummingbirds can handle very concentrated nectar, even above 30% sugars, and often prefer sucrose. Their specialised tongues and rapid licking allow them to ingest even highly viscous solutions.

Sunbirds, in contrast, generally prefer more dilute nectar with higher proportions of glucose and fructose. Their sucrase activity is much lower than that of hummingbirds, and many species avoid high-sucrose nectar because they cannot process it efficiently. Their tongues use capillary action rather than the elastic micro-pump mechanism of hummingbirds, making very viscous nectars more difficult to handle.

Returning to the original question: why is nectar beloved by birds but not by Germans buying fruit juice?

For birds, sugar is an almost ideal energy source. It is easy to metabolise, requires no chewing, cracking, or processing, and is provided freely by plants—so long as the birds keep up their side of the bargain by transporting pollen to the next flower.

Photo: Loten’s Sunbird, Surrey Estate, Sri Lanka, March 2025

For additional information on this topic – from a slightly less chemical perspective – see an earlier post, Living on sugary water: the life of nectar-feeding birds.

Fascinating.

I now understand why Proteas are limited to a high degree to the Cape floral region: their sugars do not ferment… what’s the point? Even the bureaucrats in Brussels believe fermentation is important: Under European Union legislation (primarily Directive 2001/112/EC, as amended, and specifically in the “Breakfast Directives”), fruit nectar is defined as a fermentable but unfermented product obtained by adding water, with or without the addition of sugars and/or honey, to fruit juice, concentrated fruit juice, fruit purée, concentrated fruit purée, or a mixture of these products.