Way back in 2014, when I saw my first Chestnut-sided Shrike-Vireo near the little town of Pino Real, and shared the sighting on a birders’ chat group, it took just over a month for the first biologist/ornithologist to visit me. It seems he had looked long and wide for this species. Happily, I was able to show him three individuals that day.

And after all, who wouldn’t want to see this beauty?

Since then, I have had the privilege of hosting, to the best of my recollection, nine different biologists. They have come over the years seeking specific species. For the most part, I have been able to show them the species they sought. And, in return, they share their expertise with me — definitely a win-win situation. The friendships I have formed with them is an added bonus.

And 2022 was a great year for this birder/biologist symbiosis. I’ll start with the briefest encounters. In February, I was invited to participate in a Ducks Unlimited-sponsored survey of the waterfowl (and, collaterally, shorebirds and terrestrial birds) of Lake Cuitzeo. Some thirty biologists and biology students participated, plus a single layman: yours truly. (Here is my report of that outing.) This trip did prove to me that a dedicated birder may have some advantages over scientists who spend most of their time in a classroom or lab. This would not be an issue, however, with the remaining biologists in this report — they are all certifiably bird-crazy, and live for their time in the field.

In June, my friend Alberto “Chivizcoyo” came to Michoacán specifically to see the ever-so-rare and little-known Sinaloa Martin. While I have a site at which I have seen this species for years, Alberto happened to spot a much larger number than I had ever seen, a few kilometers short of my traditional spot. It also seems to host a population of Red-breasted Chats right next to the highway; I had previously struggled to find this species reliably, and always in a more remote site. Thanks, Alberto! (If you speak Spanish, you might want to check out Alberto’s YouTube channel, “Crónicas del Chivizcoyo“. It is excellent.) You can find a more complete report of that visit here.

One of that day’s male Sinaloa Martins

And the Red-breasted Chat

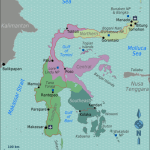

One week later, I first met a new-to-me biologist, René Vargas. Like Alberto, he made the trip to Michoacán just to see the Sinaloa Martin and, in the different spot Alberto had also visited, the even-rarer White-fronted Swift. The Sinaloa Martins were even more numerous this day in Alberto’s new spot. But, unlike Alberto, René never made it to where he had planned to look for the White-fronted Swift… because the two of us spotted one at the Martin site! (René had planned to travel 3 hours in the opposite direction to find the Swift, as had Alberto, so this was great news.) And, by helping him with the Martin, I ended up with the Swift as a lifer as well. Here is a full report of that visit.

Fortunately, René took better photos than this one of mine, allowing a positive ID.

I have the good fortune to see my fourth biologist/ornithologist, Jonathan Vargas, several times each year. Jonathan is originally from San Blas, on Mexico’s tropical west coast, and now works in the northwestern city of Ensenada. But he regularly visits family in Morelia. This year, we were able to go birding together in once in May, and twice in November. The May site is one Jonathan had spotted on Google Maps two years earlier. He suggested it to me, and it has since become one of my favorite sites. (I am eternally grateful.) But it was only in May that I could reciprocate by taking him there. I also reported on that visit here.

In November, things got a bit more biologist-complicated. Jonathan wanted to see his first Grass Wren, a species I had only seen on the property of yet another biologist, Ignacio Torres-García. “Nacho” couldn’t spend the morning with us, but he was kind enough to give us access to his property, and point us in the right direction. Multiple Wrens helpfully showed up, along with 50 other species in less than three hours. It’s a great property.

Here’s one of those Grass Wrens. Look closely. I swear it’s in there.

And here is a particularly showy Summer Tanager that turned up. (Summer Tanagers do not often show their full breeding plumage down here.) A lifer, no; a looker, yes.

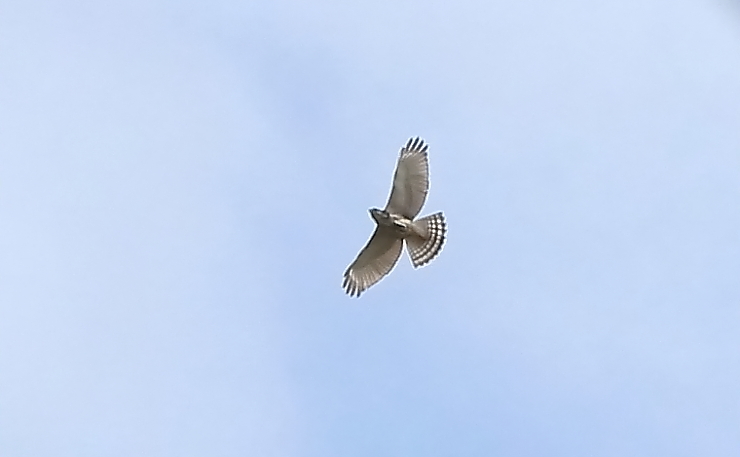

But our best outing, for me at least, was our third one. Jonathan wanted to visit Paso Ancho, so we headed downhill one week after our wren encounter. Any day in Paso Ancho is a great birding day. But this time, I got some added value from birding with a biologist who knows his tropical species. A small hawk circling overhead among some Turkey Vultures would not, in my uninformed opinion, have deserved much attention; it was clearly a common Cooper’s Hawk. But no, said Jonathan, this one was a Gray Hawk. That one over there was a Cooper’s. I had seen a couple of Gray Hawks before, but always far from “my” home territory.

The Gray Hawk

The quite-similar immature Cooper’s Hawk

I might well have figured out the difference when I saw my photos at home. But would I have known to take those photos on the field, without professional help?

And then, a bunting caught Jonathan’s eye. It was a typical brown female bunting, and I would have assumed it was a common Varied Bunting. But he got a good enough look to assure me that it was in fact a female Blue Bunting, a species usually only seen nearer the Mexican coast. Neither of us managed photos, as the bird stayed in deep brush. But, hey, when an ornithologist from San Blas swears you are seeing a Blue Bunting, you can bet the farm on it. And so, Jonathan gave me my final lifer for this year.

Since I do not have a single photo of that Blue Bunting, I’ll share one of this unusual semi-desert orchid we saw nearby.

The next biologist in my list is my friend Ignacio (“Nacho”) Torres-García, who lives on that property with the Grass Wrens. Nacho is the only non-ornithologist on this list; he is a professor of botany at a local university. I love to bird with him because he tells me all about the plants I notice while birding. Last week, he finally had some free time, and wanted to meet the high-altitude species from Cerro de Garnica. There were no lifers for me this trip, but Nacho got six. December is quite cold at 3,000 m (10,000 feet), even at this latitude. But it was well worth it. (I should also mention that Nacho went to Paso Ancho with Alberto and I back in June. There’s a lot of cross-pollination in this particular post.)

The Gray-breasted Wood-Wren was one of Nacho’s lifers. (Photo from an earlier visit of mine.)

And finally, a biologist story I have been itching to tell for months… Back in August, I received an e-mail out of the blue. A Cuban biologist and his biologist wife had been granted scholarships to study for masters’ degrees at the same university where Nacho teaches. Since he is an ornithologist (she has a different specialty), one of the first things he did was to check the eBird “Top 100” list to see if he could find a good guide for the local birds. He discovered that the current #1 birder in the state is also an evangelical pastor — with his church located only a mile from said university. (That would be me.) Talk about a collateral benefits — we now both have new birding buddies, they have a church (which made sure they had everything they could need upon arrival), and our church has a new family! And I can even say to our church that my birding, which confuses and bemuses them, has now directly benefited the congregation.

I’ll just call my friend JL, as Cubans tend to be nervous about having much of an online footprint. But I can say that it has been a blast showing him around. Our first outing, back in August, we saw 54 species — a number that JL said would be impossibly high in Cuba. And 50 were lifers for him! Numbers like that make guiding especially satisfying; and every time we’ve managed to bird together, this situation repeats itself. Eventually, I will have shown him the all of our local habitats; but for now, a very large number of species still await him.

JL was very excited about this Blue Grosbeak. It’s good for me to be reminded that one should always get excited about Blue Grosbeaks, no matter how often I see them.

While I’m the man with the cool local sites, each of my biologist friends offers something special as well. Alberto and René are two of the best birders in Mexico, with an encyclopedic knowledge of the country’s birds. Jonathan is a very scientific birder, which has both confirmed and challenged some of my own practices, and has a deep knowledge of tropical species. Nacho can identify any plant about which I ask, which is a big plus for me — I ask a lot. He is also currently the best candidate for passing me up on Michoacán’s Top 100 list, someday. Let the games begin! And JL has a fantastic ear — he told me this week that he spents lots of time listening to recorded bird songs, so he will know them in the field. In my book, that’s real dedication.

So, if you ever get a chance to bird with a biologist, you should definitely take it. You’ll be a better birder for it.

Leave a Comment