Why is the Robin’s breast red? Why are any of the parts of any birds colorful? To make it easier for birders to identify them, of course!

But seriously, Science has a more interesting set of answers, and some recently published research on European Robins helps to examine this question in some detail.

There are several reasons that scientists have postulated for any kind of signaling seen in animals, and bird’s colors are clearly some kind of signal. Here’s a short list of them:

1) Species recognition. A robin has a red breast so another robin does not mistake it for an eagle.

2) Sex recognition. Male and female birds often look different (sexual dimorphism); This is so the adult birds have procreative sex with members of the appropriate sex.

3) Territory. Birds have a sense of territory which they express through their fashion statements.

As you can see, I’m somewhat cynical about this list so far. While species and sex recognition may well be facilitated by overt and blatant signalling as we often seen in birds, there is almost no chance that showy feathers evolved for this reason. Animals can assess species and sex with much more subtle cues.

![]() Territory is not a bad idea, and certainly relates to what is going on in many cases, but the term “territory” has to mean something in order to understand what has evolved. Saying “territory” without qualification is like being a consulting for a retail corporation and saying “you will do better if your business activities improve.” You won’t get asked back for advice like that.

Territory is not a bad idea, and certainly relates to what is going on in many cases, but the term “territory” has to mean something in order to understand what has evolved. Saying “territory” without qualification is like being a consulting for a retail corporation and saying “you will do better if your business activities improve.” You won’t get asked back for advice like that.

Broadly speaking there are two kinds of competition between individuals in any species: Resources (such as food or water) which may well be distributed in a territory, and mates, which usually means females.

The first assumption you should make if you see showy, flashy, obnoxiously behaving males is that the elaborate signals relate do ….

4) Females, either actual females or territories which one would hope can include a female or two.

A male may in fact be guarding food resources which are, in turn, intended to both impress a female and feed the happy couple and the young. Or, a female may be defending a territory with similar concern over food or similar resources. This lets us add to the list …

5) Resources, mainly food.

There is another resource I want to add, which most people include under “resources” for historical reasons, but that I want to keep separate because it is special. And that is …

6) Nesting sites.

So how do colors defend nesting sites, or females, or otherwise provide a signal? And the answer to this actually becomes an item on our list of things that a red breast or other showy feature may “mean” if seen on a bird, and this item actually subsumes and works together with all of the other items on the list which we think are important. And this item is …

7) Quality. Honestly.

And no, that “honestly” I added there was not an expression of exasperation or something, though it kinda looks like that just sitting there like that. What I mean is, the colorful feathers and other signals a bird may put out there can represent quality of the individual bird (not the species or the sex) in a way that can not be lied about.

How the quality is demonstrated is the subject of one or more future blog posts, I’m sure. Briefly, the colors of the birds feathers, or some other feature including behaviors such as song or dance, have to be costly to produce so that only a high quality bird can produce them, and there can be no physiological way to produce a false signal. More subtly, the signal can directly represent a feature of the bird. A signal that indicated the ability to produce eggs or sperm would be nice for mating purposes, but I don’ t know of any readily available signal like that (though it can be done, actually). But a color that is made of a molecule that binds with, and thus made unavailable, products of starvation or infection would be an honest indicator. If a bird produces a duller red than the other birds, it could be because it is sick or a lousy forager.

Another thing a bird can be is older. Older is always better. Birds don’t die of old age (in the wild, usually) so every year a bird exists is evidence that the bird has what it takes to survive another year. In species where each sex takes care of the young, contributes to building a nest, etc. etc., either sex would do well to mate with a bird that has been around a few years, as long as there are no other contra-indicators of quality. Honestly.

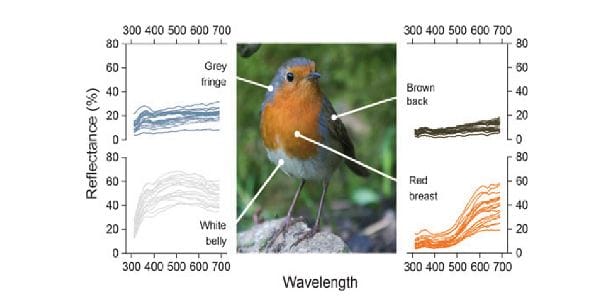

European Red Robins are quite different from the North American Robin or the Australian Robin. Both male and female have a red breast, and it is fringed with a narrow zone of gray feathers. Even though these birds have been the subject of research for decades, and were in fact studied by Lack himself, not that much is known about the overall pattern of breast color in these birds.

According to a study that was just published, literally a few minutes ago as I post this, the following pattern pertains to these robins:

As the birds age, the red area of the breast gets bigger and the gray fringe increases in visibility and contrast. The gray fringe makes the red breast more visible and impressive looking, likely. As the birds age, the male vs. female breasts grow at differential rates (the growth occurs during molts, of course) so that the dimorphism between males and females becomes greater in the adult bird.

The team’s results revealed unknown patterns of variation in the red breast and grey fringe of the robin. The size of the red breast was found to increase from the first to the second year in both males and females. However, old males showed consistently larger badges than old females after their second year.

This surprising variation across sexes and over time suggests that the red breast may convey information of sex, age or related condition-dependent traits. Moreover, researchers applied computer models that take into account environmental luminosity and bird sensitivity to study the colour contrast between feathers as seen by a robin. They found that the grey fringe, which increases in age, highlights the perimeter of the red breast.

“Our study is a first step in understanding the role of the red breast and the grey frame in the life of robins,” concluded Dr Jovani. “Further studies will likely show more surprises on the role of the redbreast and its grey frame on resolving territorial contests and mating decisions in robins”.

There is no real explanation in the paper given for this pattern (that is not the point of this excellent research paper), but I’d like to suggest something rather radical. This comes from work done with Bovids by Richard Estes.

Assume first that both male and female robins have stuff to signal, so they do so with the red breast. However, as is the case with many birds where both male and female have elaborate colors or markings, the males are signaling something different than the females. Perhaps the males are signaling quality to females to be chosen as mates by them, while the females are competing with each other for quality nesting sites. They may even be signaling over the same things, but the sex difference makes the pattern of behavior and physiology different, and thus, dimorphism.

If this is true, and it almost certainly is at least to some extent, then it may also be true that we are not seeing an increase in dimorphism in older birds, but rather, a managed, manipulated, strategic decrease in dimorphism in younger birds.

We see this in some herd animals where both male and female young have male traits. Caribou for instance; In this kind of deer, both sexes have antlers. The idea proposed by Estes years ago is this: Females produce male-like daughters (indirectly) in order to make it possible for their male-like sons to blend in to the background and avoid competition with established males. It only works when the males and females are pretty young, because the males can tell who is a male and who is a female when they are older (see above). In the case of the birds, the females could be producing male like traits prior to the first molt and at the first molt in order to conceal males and allow them to hang around and eat and be part of the flock longer (thus enhancing survival and long term mating prospects). Once you evolve male like features in females during the first couple of molts, you are stuck with them later, but they need not grow large, thus the lack of larger female red breasts in older birds, while the male’s red breasts continue to grow and become more visible (as an honest indicator of quality and age).

What do you think?

Jovani. R, Avilés. J.M., & Rodríquez-Sánchez. F (2011).

Age-related patterns of sexual plumage dimorphism in the European Robin Erithacus rubecula ibis DOI: 0.1111/j.1474-919X.2011.01187.x

Estes, Richard. 1991. The significance of horns and other male secondary sexual characters in female bovids. Applied Animal Behaviour Science Volume 29, Issues 1-4, February 1991, Pages 403-451

That is an amazingly interesting concept. But I am hardly qualified to comment further, so I’ll just wait to read what others may have to say.

Slight POV bias in that statement, it strikes me. For you, Greg, I suspect a mere slip of the pen, as you are normally more careful. But the reliance on this driving concept of competition for females, without consideration of the female POV, spoils a lot of this type of science for me.

There is a bias, but in the real life data, not my perspective. The female POV is not ignored here at all.

I don’t think I short changed the complexity in this post, but I did not go into all the details of sexual selection, dimorphism, handicap and honest advertising theory, parental investment theory, territoriality, and all the other issues relevant here. I will at some point, though; All of those things are on my list of bird stuff to blog about. I’m certainly not relying on a driving concept of competition for females if a) I listed mates (usually but not always females) second, and if the post was entirely about female strategies.

Just ruminating some more while doing dinner. I’m no scientist, although many years ago I did a degree in anthropology. I seem to remember lectures on Levi-Strauss and others who thought marriage customs could be entirely derived from the need of males to compete for females, and I always wondered what he thought the women were doing?

I do think your post is fascinating, and the suggestion that more males might survive by ‘hiding’ their maleness among similar females is something I’d never heard before.

But, the questions I’d be asking would be things like, how do the females decide who gets a shot at the reddest breasted, most honest male? Will some female inevitably end up with the poorest specimen, and why? what, in other words, is the mechanism or process by which females compete among themselves?

It is quite possible that in some bird species, the females are competing with each other for nest sites and the males are not relevant at all… until they show up and are either accepted or not by females. This seems to be the case in some South American parrot-like birds, love birds, etc. etc. Those birds are among the rare species where both males and females have wild, elaborate decorations (as in exaggerated traits) but very different ones (so they actually look like different species). Other species have the same markings, but also with distinct, signal-like traits … like bald eagles. Clearly, those white zones signal something, but you can’t tell the males from the females.

In these robins, the signals look the same, but they are not the same …. they develop differently, and thus may actually be very different (to the birds, if not to us).

The signal my be intrasexual: The male red breast would be an honest signal among males, and the female red breast would be an honest signal among females. Or, one sex may be choosing the other sex based on the signal.

The interesting thing about this study is the sexual difference and age difference (and the diff in the latter determined by the former). However, I would feel much more comfortable about suggesting the details of this set of behaviors for these robins if I knew a LOT more about this species.

But, as we discuss this, the next couple of blog posts here are certainly suggesting themselves….

Thanks for the thoughtful reply. I’ll keep an interested eye on future posts.

Could there be a Robin without a red breast. There is a bird in my garden that is exactly the same as a Robin but it has a dark grey breast. Is it a freak of nature or is there a bird similar to a Robin ?

I have recently had a bird resembling a plump robin at my feeders. However, I do not know if is really a robin. It has a very black back and head and there appears to be no color in the wings. It has the rust colored robin’s breast but there is a “V” shaped patch of white that sits just below the neck. There do not appear to be any companion birds of the same ilk. I live in coastal North Carolina, near New Bern, and as far as I know robins have not had the habit of remaining here for the winter. I can recall seeing flocks of them in Lehigh Acres, Florida at this time of year. So is this a robin, an oriole, or some other species I am unaware exists.

could be a female chaffinch there grey noy like the male…