What I truly hate about the pandemic is that it mentally puts me back into the 1990s in the Balkans. Tensions, failing economy, depression and that feeling of living day by day (under the rule of a local dictator, or, to be politically correct – but why? – “autocrat”), afraid of what the autumn brings and not being able to make plans for a longer period.

Do you remember movies depicting plague in the Middle Ages, when officials would come to your home with planks and would nail your door and windows, with you inside, only to return four weeks later to open that Schrödinger’s house and see if you are still… or aren’t. That is how I feel.

What will the world look like after they take the planks off? There will be a strong recession; that much is sure. Will bird tour agencies, guides, eco-lodges survive?

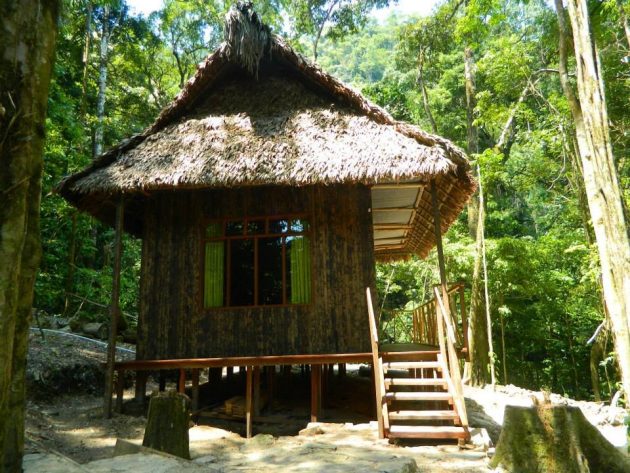

Supporting indigenous communities and conservation, Sadiri Lodge (above) is located in the Madidi National Park in Bolivia. Its main objective is saving lush lowland forest, over 30,000 ha of it. The second objective is to improve the living conditions of the indigenous people by creating access to basic needs such as health, education, electricity and communication. The locals have a large part in this venture, 75 being direct beneficiaries, 40 of whom are women. Yet, without guests, what will happen with this and similar initiatives?

Will the threatened species make it through if there are no birding tourists to make those birds and their habitats valuable to local people just the way they are (as opposed to tropical timber)? What will be left of birding tourism?

Let’s go back to the world as we knew it only a few months ago, when we freely dreamed of traveling or made plans to bird the birdiest places on Earth. The first information necessary to start planning your travels is how many birds can be seen in each country. Which countries topped the list? I was trying to find that answer for a while and it turned into a very annoying experience.

One would expect that the answer is easy to find, but no, it isn’t. There is no simple answer even to a seemingly simple question how many known bird species are recognized by the scientific community.

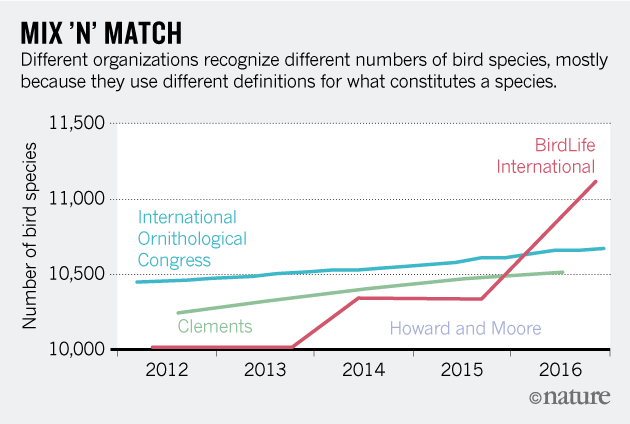

Source: Nature, 2017

Source: Nature, 2017

Here’s an example: in 2015, American birder Noah Strycker broke the global Big Year record with 6042 recorded species. Only a year later, Dutch birder Arjan Dwarshuis completed the “Biggest Year” seeing 6852 bird species. And beating the previous Strycker record by 810 species? No, since Dwarshuis followed the IOC checklist and Strycker the Clements, their totals are not fully compatible.

Attempting to update the info for the bird-richest and therefore most interesting countries, I would usually find several different lists for the same country, but often without explanation as to whether they refer to Clements, IOC or other lists. In the end I did make some sort of a working list, but not trusting the varied Internet sources, I didn’t feel like quoting that update of mine.

Hence I decided that quoting a single source makes more sense: one source should mean that the quality of data / level of bias remains uniform all along the list. That is where I chose the Avibase world checklist database (avibase.bsc-eoc.org), designed and maintained by Denis Lepage and hosted by Bird Studies Canada. Since Avibase allows you to choose between several different checklists, being an avid eBirder (and a local eBird reviewer), I opted for Clements.

Figures compiled in late November 2018 (version 2018) from Avibase alone (deliberately without any further correction from other sources) tells us that, following Clements, there were 19 countries with more than 1000 so far recorded bird species:

1. Colombia 1959 bird species

2. Brazil 1847 sp.

3. Peru 1838

4. Indonesia 1761

5. Ecuador 1690

6. Bolivia 1433

7. Venezuela 1417

8. China 1410

9. India 1341

10. Democratic Republic of Congo 1185

11. United States 1160

12. Tanzania 1135

13. Kenya 1131

14. Mexico 1120

15. Myanmar 1112

16. Uganda 1079

17. Thailand 1065

18. Argentina 1046

19. Panama 1004

Just slightly below the 1000 mark were Angola with 998 and Cameroon with 979 (followed by Australia and Nigeria, both with 970), and these contenders may join the club soon. Yet, among them, DR Congo is burdened with its long lasting guerilla war and recently with an Ebola outbreak as well (both in the bird-richest east of the country), while Venezuela is in economic and political tailspin and you would be ill-advised to go there. The others are, more or less, doing well.

Birds of Ecuador field guide review

Birds of Ecuador field guide review

Having more species than any other country in the world, combined with restored peace and returning stability, Colombia with its Andean ranges and valleys, the lowland forests of the Amazon and Orinoco regions and the isolated Santa Marta Mountains is a mouth-watering ecotourism star. Peru (Manu Biosphere Reserve with 1000 species – the richest region for birds in the world), Brazil (Pantanal, the world’s largest wetland with 650 bird species, and the Atlantic forests), and Ecuador are already well established bird tour destinations. As a small country combining Andean highlands (different species on western and eastern slopes) with Amazonian lowlands, Ecuador has more birds per square mile than any other country in the world, followed by good infrastructure and excellent local guides.

As the least accessible, Bolivia unjustly attracts less attention in this group. Being a land-locked country with 1400+ species is remarkable in its own right. My friend Chris Lotz from Birding Ecotours calls it “the world’s best kept birding secret”. “It’s unbelievable,” he says, “most people think it’s just high altitude desert, but it has the full range of habitats, except coastal/marine – it even has Amazonian lowlands”.

Birds of Thailand field guide review

Birds of Thailand field guide review

The most bird-rich northeast of India includes e.g. the Kaziranga NP and the Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, respectively, together with the world’s largest Amur Falcon roost in Nagaland. These areas offer magnificent wildlife but, apart from Kaziranga, little in terms of infrastructure. With improved stability and infrastructure, the Irrawaddy plains and Eastern Himalayas of Myanmar could offer some of the greatest bird species densities in the whole of Asia. However, Thailand with its good infrastructure and great birding, from southern rainforests for Malay Peninsula species to northern mountains in the Chiang Mai Province for numerous Himalayan foothill birds, is definitely the best area to observe the bewildering bird diversity of Southeast Asia.

Almost every 4th bird is endemic in Indonesia, a large country spread over several huge (Borneo is the 3rd, Sumatra the 6th and Sulawesi the 11th largest island on the planet) and 17,500 smaller islands, not to mention over two zoogeographical regions. Papua (western, Indonesian part of New Guinea – the 2nd largest island in the world) has 680 species (data fatbirder.com). With 580 species, Sumatra is the second birdiest Indonesian island. Indonesia has about 400 endemics (the majority of them in Papua, followed by Sulawesi/Halmahera) – more than any other in the world. Cheap flights linked most of the Indonesian islands and it was fairly easy to get a large proportion of the country’s endemics.

Kenya (Masai Mara, Lakes Nakuru and Baringo, Arabuko-Sokoke Forest) and northern Tanzania (Ngorongoro, Serengeti) combined are the birding staple of East Africa. Yet, I would advise you to also consider Uganda. Unlike the more easterly Kenya and Tanzania, Uganda lies between dry savannas of the east and Congolese rainforests in the west, combining the very best of equatorial Africa in a rather compact area. Queen Elizabeth NP offers an impressive 600 savanna species, while the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest NP offers a further 350 montane species.

But the majority of these top-countries have large surface areas. In two to three weeks of an average bird tour, you may cover several regions, but with underdeveloped infrastructure, still not much of the country. That is where Ecuador, Uganda and especially Panama stand out as being manageably small, which may be another reason to focus on them.

And now I am waiting. Waiting on those officials to take the planks off my door. What will the world look like?

Cover photo: Mabamba Bay Swamp, Uganda; photo Mike Bergin

Excellent read! Thank you! 🙂

Thank you, Marko