Andrea Howey-Newcomb is the Clinic Director at Tri-State Bird Rescue & Research, Inc. (TSBRR) located in Newark, Delaware. She holds an undergraduate degree in Wildlife Conservation with a double minor in Biology and Anthropology from the University of Delaware and a graduate degree in Wildlife Management from the University of Pretoria, South Africa. Andrea joined the TSBRR team in 1999 and has worn several hats since then, including: Intern, Senior Clinic Supervisor, Oil Programs Coordinator, and Clinic Manager. Andrea also took over running the Mississippi center during the Deepwater Horizon spill in 2010. Andrea has also held jobs as a wildlife disease biologist at the University of GA College of Veterinary Medicine (SCWDS), an intern at Maui Bird Conservation Center, a breeding facility for endangered species employed with the San Diego Zoo, a Vet Intern at Six Flags Safari, and an intern at the Philadelphia Zoo. Andrea found her passion in the rehabilitation field. Here she can give back to individual animals, offer humane euthanasia to those suffering unrepairable injuries, and educate the public on how to be stewards by coexisting with wildlife for generations to come.

How did you first become interested in bird rehabilitation? How long have you been a bird rehabilitator?

My story is interesting and unique. I went to school for Wildlife Conservation and wanted to be the next Jane Goodall. I found an internship in Africa studying lions, where I met my boss. My boss was a former employee of Tri-State Bird Rescue & Research and was always looking at birds… I didn’t really get the fascination and thought birds were a waste of my time (so foolish). She encouraged me to go to TSBRR to volunteer and build my resume. So in 1999, I did just that. I joined the TSBRR family and went on to become an intern in 2001 and a staff member in 2002. I have been with them for almost the entire 27 years.

What kind of training or education did you do to become one?

Here in the United States, aspiring wildlife rehabilitators are required to complete hands-on training under the guidance of a permitted wildlife rehabilitator. This typically involves working as an apprentice or mentee for a minimum of 100 documented hours before a mentor can sign off, allowing the individual to apply for their own permit.

Many of us also pursue certification as Certified Wildlife Rehabilitators (CWR), which requires passing a comprehensive exam that tests our knowledge of animal care, rehabilitation practices, and ethical standards. Beyond initial training and certification, there are numerous classes, workshops, and conferences available—and strongly encouraged—to ensure we stay current on best practices, continue expanding our skills, and maintain high standards of care within the field.

Can you describe your workload and activities on a typical workday or workweek?

Workload depends on seasonality. At TSBRR, we receive over 4000 birds annually (this does not include oil spills, as we are also wildlife oil responders). The clinic’s busy season is during nesting times (May-September), where we could have 300 birds in-house and have 55 new patients admitted in a day. During nesting season, the bulk of our patients are hatch-year birds, which means a lot of daily care from hand-feeding babies to cleaning out incubators/nest cups. Waterfowl hatch-year birds are particularly dirty! As wildlife rehabilitators, we are responsible for both their medical care and husbandry/diet prep/enrichment and biosecurity. In the busy season, hours and days are long. I am now a Clinic Director of the hospital, which means I have more paperwork, protocols, and legal responsibilities, and I do not always get to be one-on-one with the animals in the off-season. I find this part of my job very necessary, but boring 🙂

Do you have any particularly favoured or disfavoured bird species in your line of work?

This is a hard question for me, as I have so many favorites. I love working with Brown Pelicans as I find it easy to anthropomorphize their behaviors, and I find them to be whimsical creatures. I have always been a fan of owls as their feathers are beautiful, vultures for their attitude, pelagics watching them dive in our large pools, cedar wax wing hatch years for their socialness- watching them feed each other berries we hang in their enclosures. I often have moments where I find myself watching the behavior of the animals in their enclosures and remind myself how lucky I am to witness such things.

What are some typical positive and negative experiences as an avian rehabilitator?

The role can be deeply rewarding, but it also comes with emotional, physical, and logistical challenges. I tell everyone who brings us an injured, orphaned, diseased, or contaminated animal that they saved this bird, no matter the outcome, and all of our patients are released. We sometimes get to release them back to the wild, which is an amazing end goal we all want. But sometimes, we get to release them from pain, fear, suffering, and from broken bodies that no longer work in the form of humane euthanasia. Both are gifts, both should be celebrated. I truly believe this, and it makes my work that much more rewarding.

The most challenging aspect of my work isn’t the physical labor or even the loss of animals through death or euthanasia. What weighs on me most is when well-intentioned members of the public unintentionally cause additional harm. Often, people try to help on their own, relying on online information or personal assumptions rather than seeking guidance from trained professionals. By the time the animal reaches us, the injuries or complications can be beyond what rehabilitation can repair, leaving humane euthanasia as the only compassionate option.

This is especially difficult because, in many cases, the suffering could have been prevented with earlier intervention. It can be heartbreaking when education is resisted or expertise is dismissed, particularly when so many of us have dedicated our lives to wildlife care. Knowing that an animal endured unnecessary pain due to human choices is far harder to process than the natural losses that come with rehabilitation.

Presumably, you sometimes have birds die that are under your care – is this something you have become used to, or do you still feel it deeply?

At my clinic, we can treat suffering and pain using a multimodal approach to pain management, along with environmental modifications that reduce stress and promote comfort. I view euthanasia as a form of release, and I do not hesitate to make this decision when it is the most humane option. As experience grows and you better understand what can and cannot be saved, death becomes less traumatic because suffering can be ended more quickly and compassionately through euthanasia.

Knowing that an animal was given peace in a safe, controlled environment helps prevent burnout and provides a sense of closure. However, even with this understanding, there are days when multiple euthanasias or cases that cannot be saved leave a heavy weight on the heart. While we always strive to act humanely, the emotional toll is unavoidable at times. Ultimately, it is not the animals or the work itself that contributes most to my compassion fatigue, but rather the negative outcomes that result from public misinformation, delayed care, or resistance to professional guidance.

Could you give some examples of common, easily avoidable mistakes people make when encountering injured birds?

If you find a wild animal in need, the kindest thing you can do is not to feed it or give it water. While it feels like the right instinct, feeding can actually cause more harm than good. I like to compare it to finding an injured person on the side of the road—you wouldn’t stop to get them a meal first; you’d bring them straight to a hospital.

The same goes for baby birds. Please don’t try to feed them or rely on online feeding advice. Instead, use the internet to find the phone number of a local, licensed wildlife rehabilitator who can guide you on the best next steps.

Keeping cats indoors is another simple way to help protect wildlife. Domestic cats aren’t part of the natural ecosystem, and even well-fed pets can have a significant impact on local bird populations.

If you come across an injured bird and are able to safely contain it, it’s best not to wait to see if it recovers on its own—especially in cases like window strikes. Birds can sometimes fly away despite having serious, even life-threatening injuries. Bringing them promptly to a licensed wildlife rehabilitation facility gives them the best chance for care and recovery.

Do you see any trends in the number and species of birds requiring your attention?

Not really, but there are birds that I just do not see anymore as their numbers have declined.

You are a member of the NWRA, an association for wildlife rehabilitators – how does that help you in your work?

Yes, I am a member of the National Wildlife Rehabilitators Association (NWRA), and that connection plays an important role in my work. The conferences, in particular, are invaluable—they provide ongoing education, the opportunity to learn from experts in the field, and access to the latest research and best practices in wildlife care.

Just as importantly, NWRA offers a strong sense of community. Wildlife rehabilitation can be emotionally demanding, and being part of an organization filled with people who truly understand those challenges reminds you that you’re not alone. In addition to the camaraderie, NWRA provides a wealth of resources that help rehabilitators continually improve their skills and provide the highest standard of care possible.

When you meet people you haven’t met before and tell them about your profession, what are the typical reactions?

Most people do not truly understand what wildlife rehabilitators do. Some view us as “bunny huggers” who are simply saving animals to make ourselves feel better, while others assume the work is fun or easy. In reality, avian rehabilitation is one of the most demanding professions. It involves long hours, emotional strain, physical labor, and very little financial compensation. Despite these challenges, the work has a profound impact on conservation and on protecting our native and natural ecosystems. The responsibility we carry—to make ethical decisions, to reduce suffering, and to advocate for wildlife—goes largely unseen, yet it is essential to the health of the world around us. Be careful if you ask me what I do for a living, as I love to talk about this line of work!

What is the most rewarding release you’ve ever experienced?

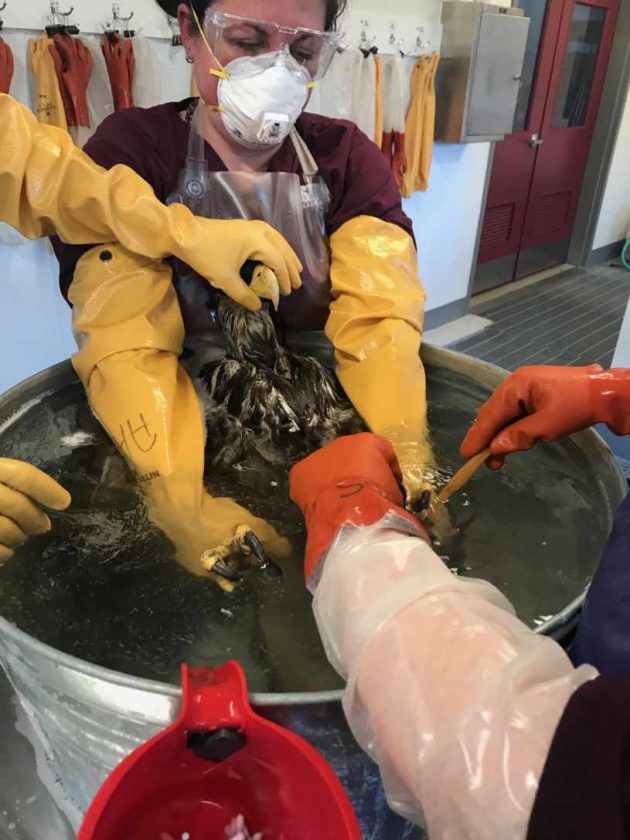

There are several that stick with me. Releasing a young Black Skimmer that I helped during Event Horizon (BP spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010). Not only did we have to wash this young bird to decontaminate it, but we then had to raise the young bird. It brought many challenges, and I was not convinced we were going to be able to ever set this bird free. When I watched this bird fly free, it was incredibly emotional, and I was so humbled by the experience.

My first raptor renesting will also stay with me. Climbing 40 feet up a tree, terrified of heights, but knowing I was giving this Great Horned Owl the best chance of life by returning it to its original family unit. This bird made a successful fledge, and I pray it is still out there creating generations to come.

Removing a small, fragile hummingbird from a glue trap and then needing to decontaminate it. I held my breath the whole time I washed this tiny creature. Miraculously, I was able to decontaminate it, and the bird was uninjured. Watching that bird fly away and stopping at a flower to take a sip brought tears to my eyes.

There are countless other stories. They keep me motivated and give me the energy to come back time and time again to help these amazing creatures.

What advice would you give birders who want to support the work of rehabilitators?

My advice to birders who want to support rehabilitators is to prioritize education and early intervention. If a bird appears injured, orphaned, or in distress, contact a licensed wildlife rehabilitator immediately rather than attempting to intervene on their own. Avoid relying on online advice or well-meaning but unqualified sources, as delays or improper care often worsen outcomes.

Birders can also support rehabilitators by helping educate the public—sharing accurate information about when to intervene, discouraging unnecessary handling of wildlife, and emphasizing that professional care is essential. Financial support through donations, fundraising, or advocating for funding is invaluable, as most rehabilitation centers operate with limited resources.

Additionally, birders can contribute by reducing human-caused injuries: promoting bird-safe windows, responsible pet ownership, habitat protection, and ethical birding practices. Finally, showing respect for the emotional and ethical weight of rehabilitation work—rather than minimizing it—goes a long way in supporting those who dedicate their lives to this field.

Leave a Comment