When I started to bird around my home city, my whole attention was focused on species. Once I became familiar with most of those that allowed me to observe them, my focus switched to bird families, the main focus of my international travels. And recently, I noticed that my way of birding is going through a new transformation. Instead of focusing on species and families, I am focusing on their habitats.

I used to chase birds wherever they were, from rubbish tips to cattle carcass depositories… and got sick of such places! Enough is enough. So, early last year I gave up the bird seasonality and visiting their congregations. Instead of getting frozen from the however light breeze at the place where the river is two miles wide and paved with ducks, I went into the forest.

Visiting winter wetlands, I am certain of 30 to 40 species. In the winter forest, I’ll get 20 of them. But there will be no plastic bottles that wind has swept from the water onto the bank, and apart from an occasional truffle hunter, there will be no people. Paying no attention to the bird numbers, I started visiting the best preserved habitats nearby. And afterwards, I often feel rejuvenated. Am I getting free of my OCD?

To better understand those best preserved and other habitats around, recently published Habitats of Europe by Dale Forbes, Iain Campbell, and Pete Morris covers the continent’s 56 major habitats. While some habitats could reasonably be classified under multiple biomes, each is described only once.

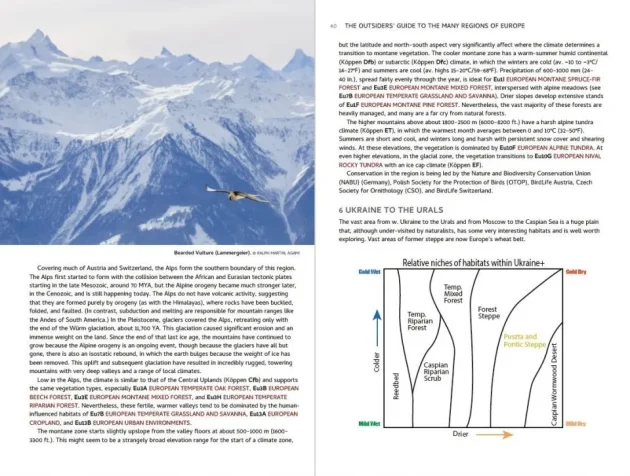

This book covers all of continental Europe, east to the Urals and including Türkiye, Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan. It excludes the Canaries, as these are treated in the Habitats of Africa book, and Greenland, covered in the Habitats of North America book.

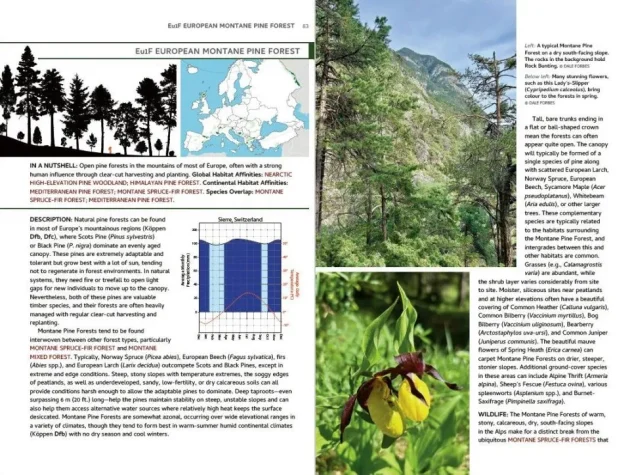

Habitat accounts start with a habitat silhouette, showing some of its distinctive plant shapes, its overall height and structure, including a human silhouette for scale. Next to it stands a range map. Dark shading is used for areas where the habitat is the predominant habitat, or one of the predominant habitats. In some maps, pale shading is used to indicate areas where the habitat is found only sporadically. Also, each major habitat is accompanied by an illustrated climate graph that allows easy comparisons between habitats.

The textual descriptions are a real gem. They are down to earth and read like a great where-to-watch-birds guide, nowhere near the usually boring scientific descriptions. A description explains what makes a habitat distinctive and how it works. Some of the commonly included information is the height and composition of the various layers of vegetation, the overall ‘feel’ and accessibility, local temperature, and rainfall. Considering wildlife, larger mammals and birds are the primary focus (for birds, the authors followed the eBird-Clements taxonomy). The next section provides a quick summary of the conservation status of the habitat and major issues it is facing, followed by Where to see: the finest examples of parks and reserves holding the described habitat.

The broad habitat categories and subcategories used in this book are clustered by biomes, and this book recognises conifer forests, deserts, temperate broadleaf woodlands, savannas, grasslands and steppes, Mediterranean shrublands, tundras, freshwater habitats, saline habitats, and the anthropogenic habitats.

Surely, understanding habitats in detail is essential to any birder who wants to get the most out of his experiences in the field. Why do the local habitats look like they do, or why are those particular birds characteristic of them?

For example, the other day I birded the Deliblato Sands Reserve, an hour east of Belgrade—the largest inland sand dunes area of Europe, covering 38,000 ha and holding valuable complexes of grazing pasture, steppe, woodland, and scrub. Let me see what can I find about its habitats… I should check the chapter on Grasslands and Steppes? More specifically, the European forest steppe: “The steppe bird assemblages unsurprisingly contain Eurasian Skylark, Meadow Pipit, … European Stonechat …, all keeping a watchful eye on the sky as … Booted Eagle, Montagu’s Harrier, and Eurasian (Common) Kestrel cruise by. … The forest-steppe mosaic is great for Fieldfare, Wood Lark, Tree Pipit, Yellowhammer, Ortolan Bunting, Grey Partridge, and Red-backed Shrike.” Yep, it fits – in short, Deliblato Sands would fall under the European forest steppe.

Nothing short of impressed, I’ll boldly say, every European birder and environmentalist needs a copy! Absolutely highest recommendation.

Habitats of Europe: A Field Guide for Birders, Naturalists, and Ecologists

Book by Dale Forbes, Iain Campbell, and Pete Morris

Paperback – December 2, 2025

432 pages, colour photos, colour illustrations, colour distribution maps

Publisher: Princeton University Press

Leave a Comment