What is your favorite bird book of all time? Frankly, I’m surprised seven of our 10,000 Birds writers could make a decision. Read about their favorites and then let us know what is selection. Don’t worry, you can change your mind next time we run this list, because I’m sure some of us will change ours. There’s just too many excellent, memorable bird books out there!

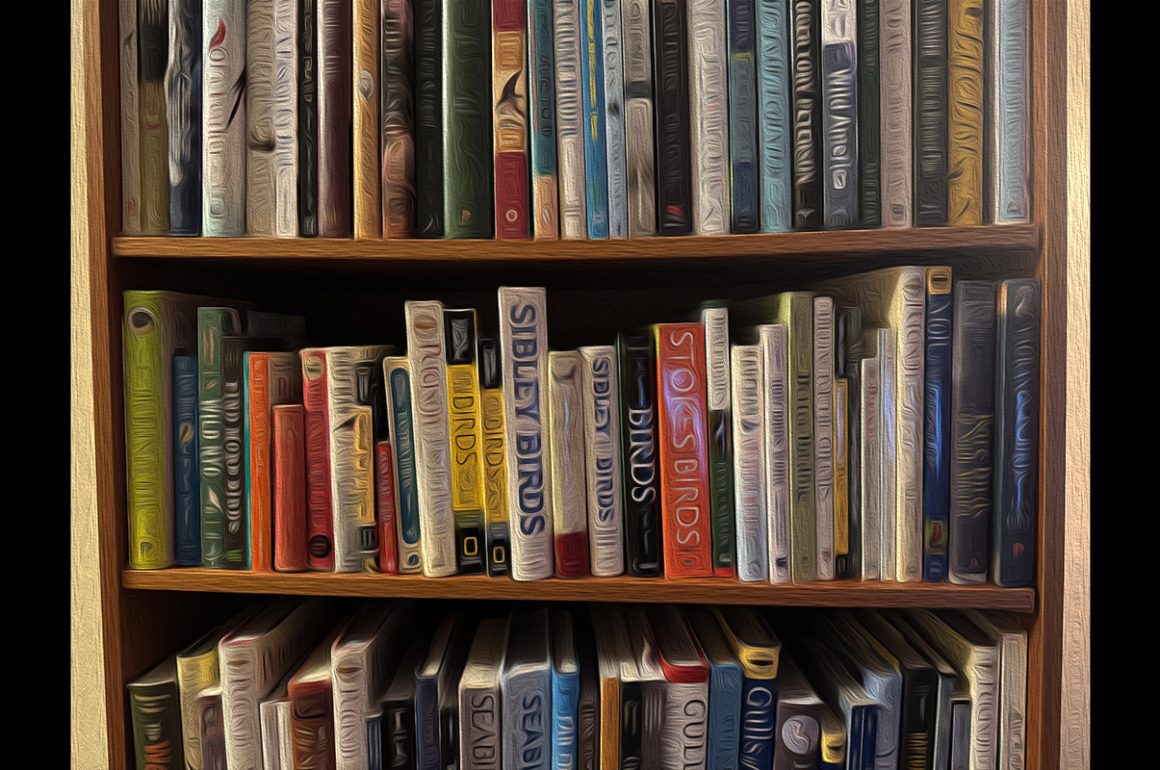

Erika Zambello: Life List: A Woman’s Quest for the World’s Most Amazing Birds

Erika Zambello: Life List: A Woman’s Quest for the World’s Most Amazing Birds

When I was in my twenties, I fell in love with birding. When I fall in love with something, I read everything I can get my hands on magazines, articles, how-to’s, and, of course, books. That’s how I discovered Life List: A Woman’s Quest for the World’s Most Amazing Birds, a biography of Phoebe Snetsinger written by Olivia Gentile. Published about a decade after Snetsinger’s tragic death in Madagascar, the book chronicles her early life, her battle with cancer, and her quest to see as many birds as possible. When she died, Snetsinger had seen more than 8,300 species across the world! In fact, she was the first person to list 8,000 birds.

This book made a big impact on me. At the time, few birding books had been written from a woman’s perspective, highlighting the additional challenges a global birder faces if she is female. Moreover, Snetsinger wasn’t an ornithologist or a scientist, she just loved birds. Well, and she became obsessive. This was also one of the first books I’d read that showed in stark detail the rewards and consequences of listing when it becomes an obsession (Snetsinger skips her mother’s funeral, her daughter’s wedding, and sustains major injuries). A siren call, and a warning, all wrapped up into one biography.

Because I read Life List so early in my birding years, it informed what kind of birder I wanted to be. Did I want to keep track of my bird lists? Oh, yes, absolutely. Did I want to dedicate my entire life, all my time and financial resources, to see more than 8,000 birds? Nope, no I did not. In a way, it was a little sad. I love traveling and seeing so many birds would be thrilling; but the cost seemed too great. As a consequence, however, I remain devoted to my neighborhood and regional birds, and instead have dedicated my career to protecting them. Not a bad trade, as far as I can tell.

I’ve read Life List, twice, which is rare for me, still captivated by Snetsinger’s determination and Gentile’s lovely writing style. I highly recommend it to birders, travelers, and the curious.

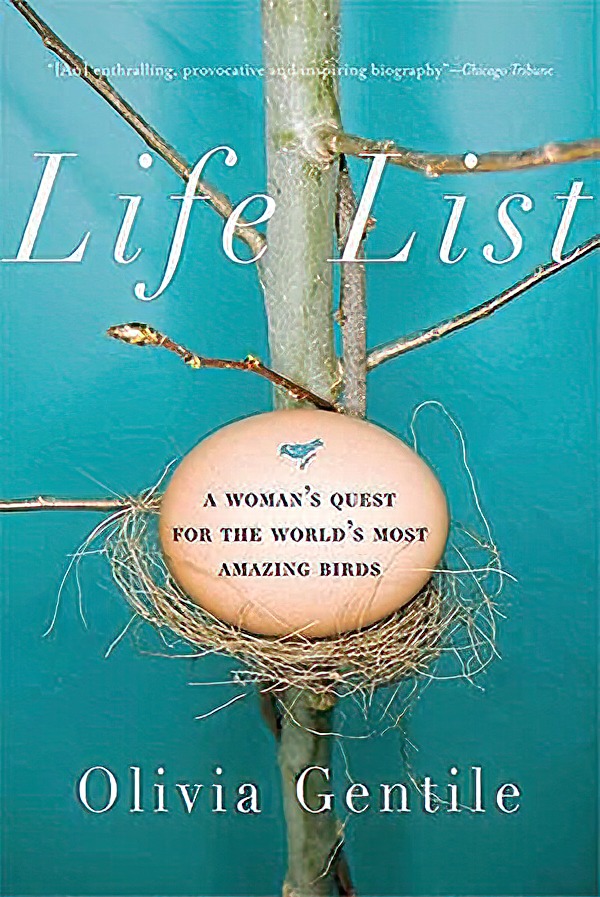

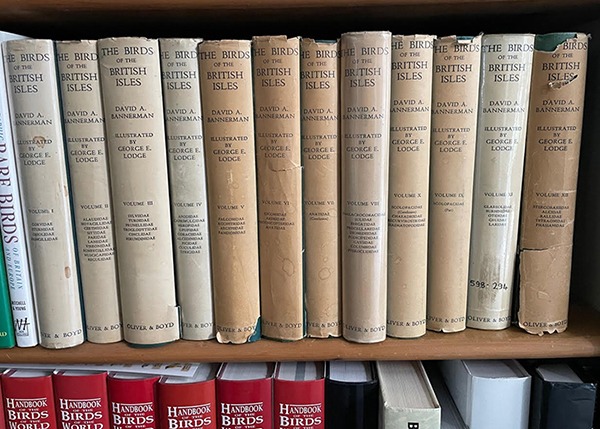

David Tomlinson: The Birds of the British Isles

David Tomlinson: The Birds of the British Isles

I’m probably the only person who has chosen an old book (or, rather, a 12-volume series of books) as my No 1 choice.

I’m writing this in my study, surrounded by hundreds of bird books, collected over many years. The fact that I once did a great deal of book reviewing partly explains why I have so many, but there are also numerous books that I paid for. My favourite genre is field guides, and I’ve got much of the world covered, from Chile to China, Australia to Argentina. I’ve got several different editions of A Field Guide to the Birds of Britain and Europe. My original copy I received for my ninth birthday (it’s the third revised edition, 1958). Now very battered and in need of rebinding, it’s a book that I read from cover to cover as a child, so is a contender for my all-time favourite.

However, if I had to pick out one title that I would take to my desert island, then it has to be The Birds of the British Isles, written by David Bannerman and illustrated by George Lodge. It’s a 12-volume work, with the first published in 1953, the last issued 10 years later. That does mean, of course, that it’s now much out of date, as bird populations have changed radically over the past 60 years. However, what makes this work so special is the text. Each species is dealt with in considerable detail, but the accounts are not the dry, factual texts so typical of modern bird books, but highly readable essays. If you’ve got a spare half hour, then a great way to spend it is to browse through one of these splendid volumes. You will not only be entertained, but will also learn a great deal at the same time.

I collected my set of Bannerman volume by volume, an exercise that took me many years to complete, as by the time I tracked down the last missing book the series had been out of print for a long time. These days you can buy the complete set from a second-hand book dealer for as little as £200, a genuine bargain.

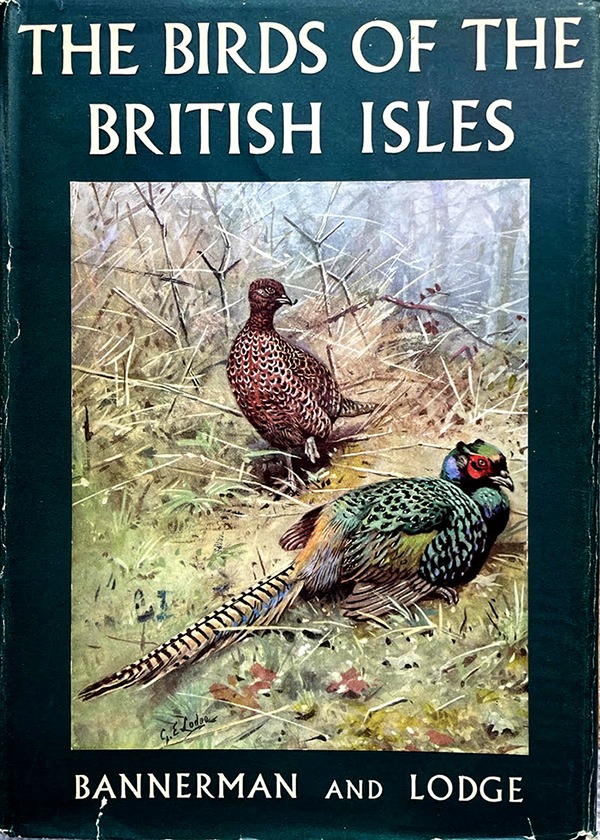

Carroll, Catherine: Kingbird Highway & Hope is the Thing with Feathers

Carroll, Catherine: Kingbird Highway & Hope is the Thing with Feathers

In his forward written for Orion Magazine’s 2023 book Spark Birds (also published as “The Problem of Nature Writing” in The New Yorker, August 23, 2023), Jonathan Franzen writes, “To succeed—to get people to care about preserving the world—it can’t be only about nature.” Referring to the Spark Birds collection he writes, “Common to all the essays is that, by focusing not only on birds but on human characters, they avoid the pitfall of preaching only to the converted” (p. xv). I must agree with him because this is the kind of “bird writing” I like reading. I probably shouldn’t admit this, but there are many famous and award-winning nature and bird writing authors whose books I have not been able to get through.

So here goes. As it turns out I have two such books. Are they my favorites of all time? Well, they come as close as any I can think of.

My first book is Kingbird Highway: The Story of a Natural Obsession That Got a Little Out of Hand by Kenn Kaufman (1997, reprinted with a different subtitle and afterword by Kenn Kaufman in 2006). In the United States it may be a safe guess that most birders have heard of Kenn Kaufman’s book, even if they have not read it. I love “Big Year” books. Big year birders are confident, goal oriented, highly motivated individuals and always find a lot of birds. But their real struggle is an internal struggle. Kaufman’s Kingbird Highway is the pinnacle of this kind of writing. Against his teachers’ advice (he was 16 years old and a good student), Kaufman dropped out of high school to hit the road for a birding big year. He did have the blessing of his parents who understood their son. He had no money and no transportation—hint, he hitchhiked, and he walked, often many miles. His first attempt fails, but with this effort he learns. He returns home to regroup and then heads out a second time. He still has no money or transportation, but he has met and learned from other birders, and he makes his second attempt a success.

Along the way readers experience his difficulties: where to sleep, being hungry, walking miles alone to find a bird, his loneliness. He meets random people who help him, and he forms friendships with other birders who he can count on and who teach him. No doubt, some of those friendships he still has today. Kenn Kaufman writes like a Fine Arts major. He never did finish high school and I read that many years later he was invited back to his former high school to receive an honorary diploma. I have a friend involved in higher education with a top university. He believes that Kingbird Highway should be required reading for all high school students.

Kingbird Highway was Kaufman’s first book, but not his last. I can safely recommend any of his literary non-fiction to readers. It is also worth reminding new and modern-day birders that Kaufman did his big birding year in the early 1970s. No cell phones, no Internet, no eBird, no Merlin ID, no apps, no social media, no digital cameras, and no credit cards. In those days there was word of mouth, “rarity hotlines,” and friendships. That’s it. Yet Kaufman’s writing is as fresh as ever. As it turned out, Kenn Kaufman was not the top birder in his big year. He missed out by only a few species. However, as readers will understand, this turns out to be beside the point.

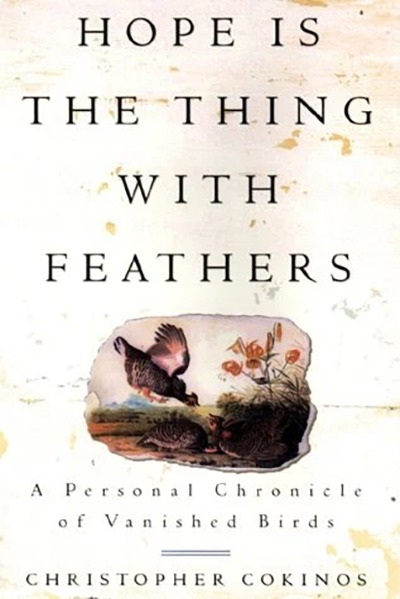

Another favorite all-time bird book is one that many birders and readers are unlikely to know: Hope is the Thing with Feathers: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds, by Christopher Cokinos. I’ve used up all my words with my first favorite book, so this second entry is more to make sure readers are aware of this book. Corkinos’s research, astonishing writing, and storytelling make this book hard to put down. He writes about the Carolina Parakeet, Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Heath Hen, Passenger Pigeon and, finally, the Labrador Duck and Great Auk. I don’t think it is too much to say that the birds come back to life in his writing. One does not need to be a birder to be riveted by this book. Its appeal is for all readers. Now that I have pulled it off my shelf, it’s time for a second read.

Another favorite all-time bird book is one that many birders and readers are unlikely to know: Hope is the Thing with Feathers: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds, by Christopher Cokinos. I’ve used up all my words with my first favorite book, so this second entry is more to make sure readers are aware of this book. Corkinos’s research, astonishing writing, and storytelling make this book hard to put down. He writes about the Carolina Parakeet, Ivory-billed Woodpecker, Heath Hen, Passenger Pigeon and, finally, the Labrador Duck and Great Auk. I don’t think it is too much to say that the birds come back to life in his writing. One does not need to be a birder to be riveted by this book. Its appeal is for all readers. Now that I have pulled it off my shelf, it’s time for a second read.

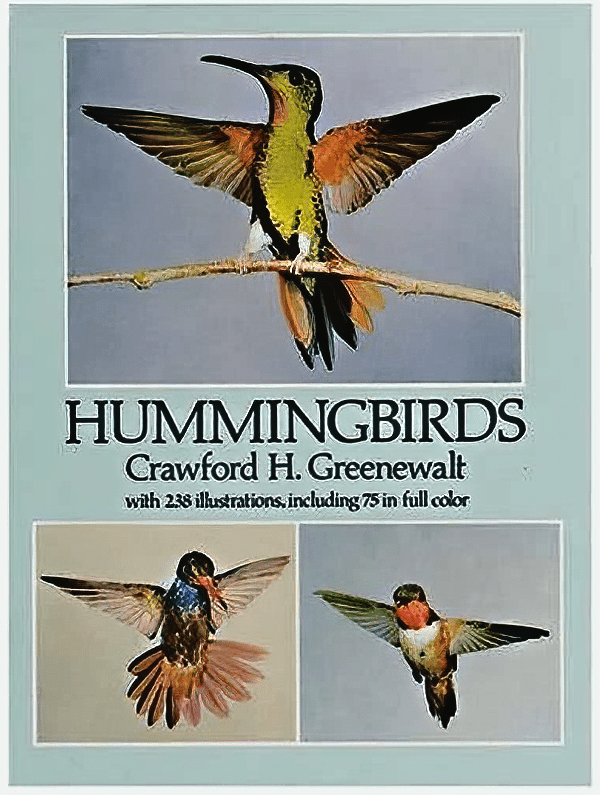

Leslie Kinrys : Hummingbirds by Crawford H. Greenewalt

Leslie Kinrys : Hummingbirds by Crawford H. Greenewalt

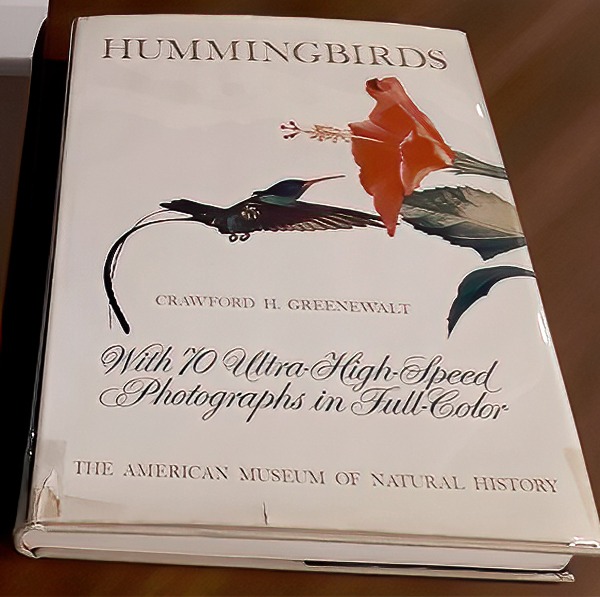

Years back, we were at a book show. Everything was old or collector’s items, and all the books were for sale. I passed a table and saw something special. It was this impressive book about hummingbirds. It was a pricey item, but I kept circling back to it. The seller said she knew I was going to be the book’s new owner.

This book was published in 1960. Greenewalt was a chemical engineer, who brought his scientific expertise to the study of hummingbirds. He was not an ornithologist or even a birder, but he found others who helped him in his quest to photograph all the hummers depicted in the book. But the book is not a dry, dull study of hummingbirds. There is information about behaviour, iridescence, flight and characteristics. His colour photographs were considered superb for the time and I think they are comparable to today’s photographs. Sometimes, he photographed captive birds, but they were still amazing studies. The photographs are all life-sized, with short bios about each bird.

This is the book I would want if I was stuck on a deserted island.

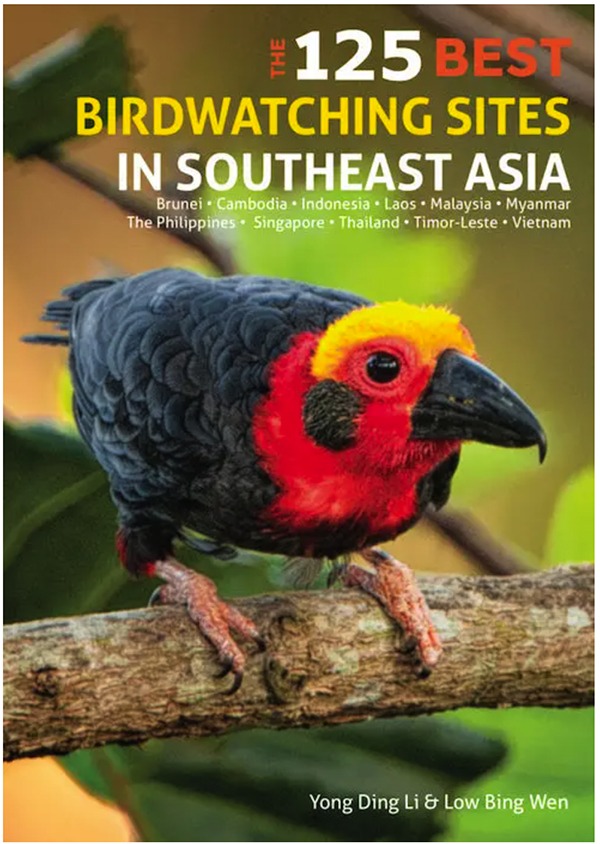

Kai Pflug: The 125 Best Birdwatching Sites in Southeast Asia

Choosing my favourite bird book is not easy. The obvious choice would be the Handbook of the Birds of the World—except that these days I only ever use the online edition. One of the field guides to the birds of China, maybe the Princeton guide, was another candidate, but field guides don’t exactly give me a warm, fuzzy feeling. And of course, I could have chosen my own photo book on the birds of Nanhui, Shanghai—though the next logical step from there would be demanding a Nobel Peace Prize. I’m not quite that shameless yet.

So my choice is admittedly less dramatic: the book I actually use most often, usually to decide where to go birding within my wider neighbourhood—The 125 Best Birdwatching Sites in Southeast Asia.

Yes, I know: it’s not an inspired choice. The book is exactly what the title promises—descriptions of 125 birdwatching sites across 11 Southeast Asian countries. Each site gets two or, more commonly, three pages with a standard set of sections: general notes on geography and habitat, typical and notable species, best seasons, practical information on access and accommodation, and a short summary of conservation issues. About half of each entry focuses on specific birding spots within the site (“Km 69 roadside” is an example) and the key species you might find there. Every entry includes a small map, a few good photos of highlight species, and often one showing the wider landscape.

Nearly 40 contributors wrote the site descriptions, and in my impression, all are knowledgeable experts. While it isn’t a book to read from start to finish, picking it up at random and browsing different sites has—more than once—been the beginning of a decision-making process that ended with an actual birding trip. And although some details are now a bit dated (the second edition came out in 2019), it remains accurate enough for the kind of early-stage trip planning I use it for.

Jason A. Crotty: Of a Feather: A Brief History of American Birding

Jason A. Crotty: Of a Feather: A Brief History of American Birding

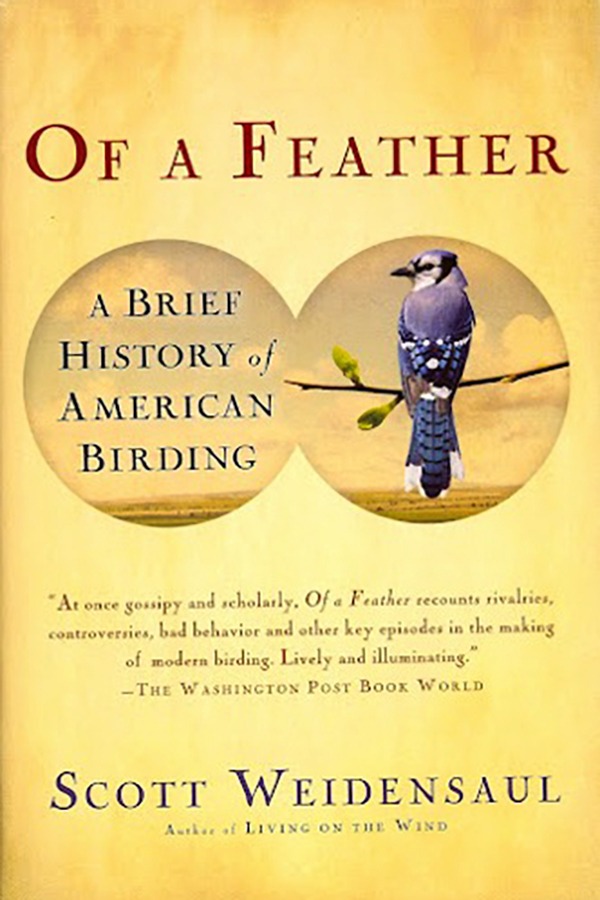

Scott Weidensaul has written broadly on bird-related topics and all of his books and articles are worth reading. However, one of my favorites is Of a Feather: A Brief History of American Birding, which was published in 2007. It is a readable and wide-ranging chronicle of birding, with chapter titles such as “Shotgun Ornithology” and “Angry Ladies.” Alexander Wilson, John James Audubon, Harriet Lawrence Hemingway, and Robert Tory Peterson make appearances, and there are valuable overviews of the development and evolution of field guides and recording bird sounds. The creations of the National Audubon Society and the American Birding Association are engagingly presented, as are the beginnings of bird counts, listing, and big days. It is always valuable to know some of the history of one’s chosen pastime, particularly when reading it is such a pleasure as well.

Donna Schulman: Peterson Field Guides Eastern Birds

Donna Schulman: Peterson Field Guides Eastern Birds

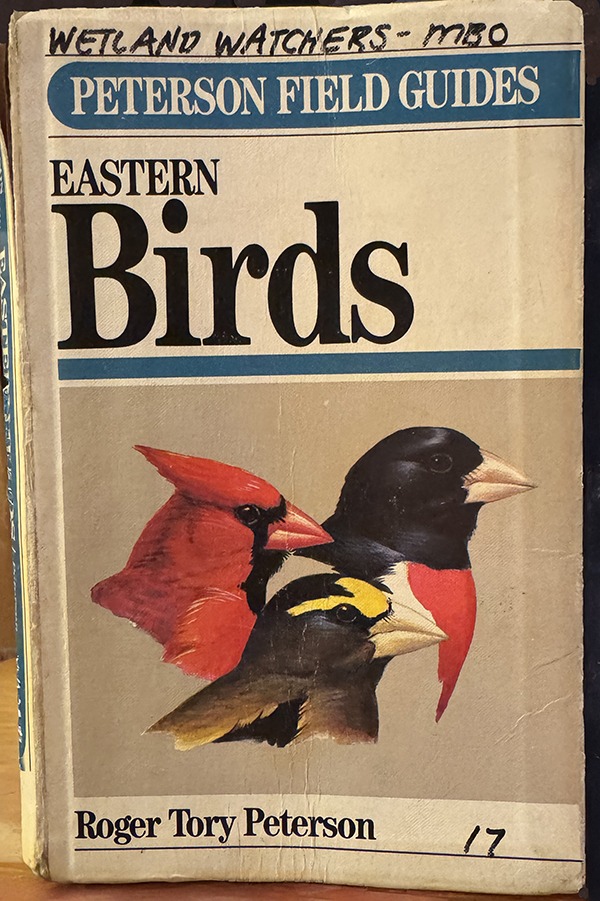

It took me a long time to narrow it down to one book. Like food, there are books I love at certain times of the year, but then eventually move to the friend zone; books that prompt memories; books that I consult regularly for identification; books written and illustrated by friends. I’ve finally decided on Eastern Birds of the Peterson Field Guides series, fourth edition, completely revised and enlarged, 1980 by Roger Tory Peterson (official name A Field Guide to the Birds: A Completely New Guide to All the Birds of Eastern and Central North America). This was my first field guide, one of the used guides distributed to me and other participants of my beginning birding course by our teacher, Starr Saphir. The course was sponsored by NYC Audubon (its name at the time, now NYC Bird Alliance) and the only reason I was there was because my daughter had left for college the previous year and I had a lot of time on my hands, so when a friend told me she was taking a birding workshop, I said, “I’ll go too.” I don’t remember being very interested in birding, I simply needed something to do. My friend was bored and I was hooked.

Starr gave me the Peterson guide before our first field trip to Central Park. It’s front and back covers are marked “Wetland Watchers–MBO” in magic marker and “17” in the lower right-hand corner, so I imagine it was used in an educational program at some point and eventually placed on the give-away shelf. A field guide copyrighted 1980 was very much out of date in 2002, but this did not occur to me for a long time. Ironic considering this is the first thing I think about now when handed a field guide! This was before splits took over birding taxonomy, only Rufous-sided Towhee had to be corrected (which I did with “Eastern” in big letters). I carefully annotated the listings with the date and place of my first sightings–Bufflehead, Feb. 2003, Jamaica Bay; Eastern Phoebe, Sept. 2002, Central Park; Black-and-white Warbler, April 2003, Montrose Point, Chicago. But maybe not so carefully: “3-03 FMP” next to Red-necked Grebe is puzzling–the grebe is rare in New York City in March and Flushing Meadows Park (FMP) would be a strange place for it. What did I see?

My birding teacher, Starr Saphir, was a birder of some reputation in local birding circles, though I didn’t know it at the time. She had been leading bird walks in Central Park for over 20 years when I became her student, and became wider known a few years later when she appeared in Jeff Kimball’s documentary The Central Park Effect in 2012. Like Phoebe Snetsinger, another woman birding hero (see Erika’s book choice above), Starr was diagnosed with cancer and then proceeded to bird like a madwoman till she died about 11 years after her diagnosis (in Phoebe’s case, it was 18 years).

It is a bit of an exaggeration, though, to say that Starr birded like a madwoman. She was careful and structured and had rules: No pointing! Learn to describe the bird’s location. No chatter! Put your field guide away and observe the bird from an appropriate distance; look for field marks; make notes. Only then should you take out your field guide to confirm your identification. This last rule made impatient me crazy. A year after I took Starr’s class, I was at the East Pond of Jamaica Bay NWR, sitting on a rock, watching newly arrived autumn ducks and comparing them to the drawings in my Peterson Field Guide. I heard people coming, spied Starr’s signature blue bandana through the branches, and quickly put the field guide behind my back. “I saw you!” she exclaimed. I grimaced, embarrassed. But it was all good. Starr introduced me as one of the successes of her previous class and I watched the new batch of students try to focus on Buffleheads, Ruddy Ducks, and Northern Shovelers. I saw the blue binding of the Peterson Field Guide sticking out of one man’s backpack. Starr was still distributing old guides from the give-away shelf.

LIST OF FAVORITE BIRD BOOKS (in order of essays)

Life List: A Woman’s Quest for the World’s Most Amazing Birds, by Oliva Gentile. Bloomsbury, 2010, 352 pages.

The Birds of the British Isles, 12 volumes, written by David Armitage Bannerman and illustrated by George E. Lodge. Oliver and Boyd, 1953.

Kingbird Highway: The Story of a Natural Obsession That Got a Little Out of Hand (original title, also subtitled The Biggest Year in the Life of an Extreme Birder in later editions), by Kenn Kaufman. Houghton Mifflin, 1997; reprint edition with afterward by Kaufman, Mariner Books, 2006.

Hope Is the Thing with Feathers: A Personal Chronicle of Vanished Birds, by Christopher Cokinos. J. P. Tarcher, 2000, 359 pp.

Hummingbirds, by Crawford H. Greenevalt. Published for the American Museum of Natural History by Doubleday, 250 p. 69 color plates.

The 125 Best Birdwatching Sites in Southeast Asia, 2nd ed., edited by Yong Ding Li and Low Bing Wen. John Beaufoy Publishing, 2019, 404 pages.

Of a Feather: A Brief History of American Birding, by Scott Weidensaul. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2007; reprinted by Mariner Books, 2008, 358pp.;

A Field Guide to the Birds: A Completely New Guide to All the Birds of Eastern and Central North America, fourth edition, completely revised and enlarged, by Roger Tory Peterson. Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

Here’s another vote for Kingbird Highway. It’s a righteous quest to set out on a big year with no money in your pocket. I would rather re-read this book a third time than read how someone blew $100,000 in airfare aiming for a bigger number.

Life List: A Woman’s Quest for the World’s Most Amazing Birds is a book I have read too. Could Snetsinger have done more with the huge inheritance and the windfall of extra life? I think so. I agree with Erika’s assessment of the person in that sense. I also read Kingbird Highway and it was a fun read but the waft of seventies hippies became a bit much at times. The 125 Best Birdwatching Sites in Southeast Asia is a much better read: the book allows for daydreaming of new destinations.