Morning at the slopes of Mt. Povlen, a quick stop filled with a song that sounds familiar, but I haven’t heard it since last year. Checking it on my phone – yes, it is an Ortolan Bunting!

Our destination lies further west, along the Drina River, which marks the border between Serbia and Bosnia. We are heading to the 6 km / 4 mi long and 500 m / 1600 ft deep Tresnjica River Gorge, on a small tributary of the Drina originating on the slopes of Povlen – and a Griffon Vulture Sanctuary.

I am driving by the fast, green currents of the Drina, trying to spot an unmarked and narrow uphill turn off prior to the official nature reserve turn off. This may be it, I was thinking, but only when I reach the turn off for the Tresnjica village and gorge, I knew that that was it. So I drive about a mile back and after a sharp turn find myself enveloped in a soothing shade of a beech forest. Common Chaffinches and Great Tits are calling from several directions at once, but even such extrovert birds are surprisingly hard to spot among young leaves.

The unpaved road winds up the hill, through a traditional farming landscape of small gardens, meadows and raspberry fields with thickets of the Oriental hornbeam, Turkey and Italian oak, black pine and prickly juniper, where Common Whitethroats (above) and Eurasian Blackcaps sing and Eurasian Blackbirds chase each other. We even asked one elderly villager where to look for Griffon Vultures and got the answer: “In the raspberries.” (No, they weren’t in raspberry fields.)

Due to mass wolf poisonings in the 1960s and the 1970s, Griffon Vultures in Serbia suffered a dramatic population crash. Yet, in the late 1970s there still were six colonies with about 40 breeding pairs left, but in the early 1990s only two colonies and 22 pairs persisted (of which only 13 bred in 1991) – five of them in this gorge.

The first sign that we are getting close were the Common Ravens, a few dozens of them. There are very few sheep in the meadows and too few animals end up dead in the open, where scavengers can get them. Hence, vultures rely on a feeding station where they are provisioned with slaughter house offal and occasional carrion. And the vulture restaurant attracts other guests, such as ravens.

After the first two vulture restaurants were opened in Western Serbia in 1990s, the population recovered, they even attracted birds from the then war-torn Herzegovina to move in. Nowadays there are about 140 pairs in the country, about 25 of them in the Tresnjica Gorge.

A Song Thrush is singing, while one Sombre Tit makes a short, but heartily welcomed appearance. We approach a low limestone cliff topped with separate rock formations, like a medieval city wall topped with parapets that offered protection to defenders. And the cliff was white with bird droppings. Some large bird droppings… several birds are warming themselves in the morning sun at the parapets. Each bird has its own merlon. The birds are big, brown with white neck ruffs… did I say big? They are huge!

We are observing our targets for today: Eurasian Griffon Vultures! One would take flight, soon to be replaced with another bird, but in general, they couldn’t care less about us. It is their style of complementing our physical shape in a vulture-flattering way, something like saying: “You’re not dying any time soon, are you?”

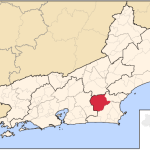

The Tresnjica Nature Reserve lies 180 km / 110 mi southwest from Belgrade (it is the upper one of the two green areas in Serbia on this distribution map by BirdLife International; red being a frightening extinction zone) and albeit a rather tiresome drive on local roads, can be done as a one-day excursion from Belgrade. Through the gorge there is only a hiking path offering some impressive vistas of towering cliffs and soaring birds.

is that the best post title ever?