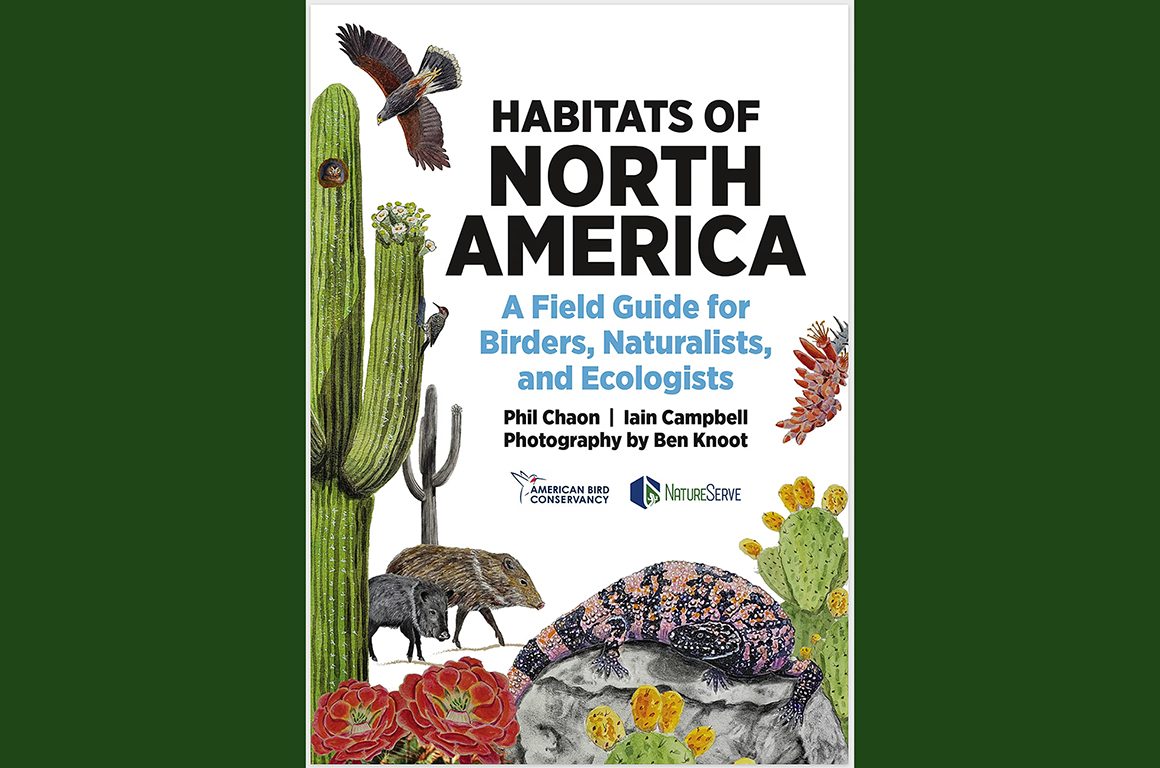

Habitat, a word whose definition can be simple or elastic or adapted to specific purposes. There is Habitat for Humanity; Habitat, the British home furnishings retail brand; Habitat Magazine, devoted to news for NYC cooperative buildings, Habitat Clothing, a number of books entitled Habitat or Habits on home decorating, gardens, aquariums, and CGI images of animals in fantasy-quality scenery. The Oxford English Dictionary definition of habitat is “the locality in which a plant or animal naturally grows or lives,” derived from the Latin habitat, the third-person singular present tense of the verb habitare. This is what we’re interested in here, of course. Habitat is often a tiny section of birding field guides. In 2021, a group of bird guides with backgrounds in ecology and a tendency to think outside the box thought the concept deserved more–more thought, broader definition, more application to birding–and put together Habitats of the World: A Field Guide for Birders, Naturalists, and Ecologists, a book describing 189 of the world’s major land areas/biomes/habitats. It was a notable accomplishment, involving rethinking traditional definitions of what “habitat” means, and devising new vocabularies and criteria. It was fascinating and a little overwhelming. We now have the next step: four guides to the habitats of major world land masses, two published in 2025 (North America and Africa) and two to be published in 2026 (Europe and Australia, New Guinea, & the Solomons). In this review, I’m going to talk about Habitats of North America: A Field Guide for Birders, Naturalists, and Ecologists by Phil Chaon and Iain Campbell, with photographs by Ben Knoot, developed in cooperation with the American Bird Conservancy and NatureServe, a nonprofit specializing in biodiversity data.

This is an amazing book, one I enjoyed reading and browsing through much more than I did Habitats of the World, perhaps because the smaller geographic areas are much more focused and easier to digest, perhaps because I’m familiar with many of the habitats described and have high hopes of getting to know the ones I haven’t experienced. The book truly covers North America–Canada, the United States, Mexico, Greenland, the Aleutian Islands, the Hawaiian Islands, and most of the Caribbean islands (not those off the coast of South America, such as Trinidad and Tobago). (Geographically, Hawaii is not part of North America, but I understand the reasons why it’s been included here, a nod to its inclusion in the ABA (American Birding Association) official area and its interest to North American birders.) The authors define “habitat” as an “ecosystem.” They determined the 81 habitats in this book using two criteria: (1) visual distinctiveness, and (2) assemblage of wildlife, primarily birds but taking mammals and other creatures into consideration. The latter is what makes their system unique.

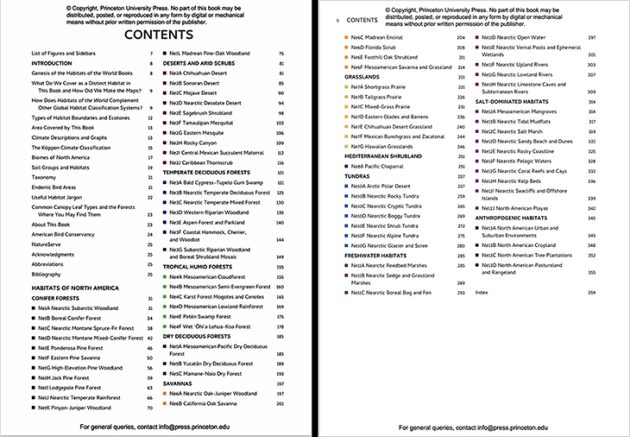

© 2025 Phil Chaon, Iain Campbell, and Ben Knoot, Contents

© 2025 Phil Chaon, Iain Campbell, and Ben Knoot, Contents

The habits are organized into 12 “ecological communities,” also called biomes: conifer forests; deserts and arid scrubs; temperate deciduous forest; tropical humid forests; dry deciduous forests; savannas; grasslands; Mediterranean shrubland; tundras; freshwater habitats; salt-dominated habitats; anthropogenic habitats. It’s a wild ride through ecosystems, starting with Nearctic Subarctic Woodland in the north, passing through stunning conifer forests, severe deserts, familiar riparian woodlands, dreamy cloudforests and rainforests, prairies of shortgrass, tallgrass, mixed-grass, back to tundra that is rocky, cryptic, boggy, and alpine, into marshes, bogs, and fens and then into the saltwaters of mudflats and coasts, and finally ending with the habitats in which most of us live and work–cities, suburbs, cropland, pastureland. Strangely, there is no map showing the distribution of the 81 habitats for all North America, or even the 12 biomes, despite a color-coding system that attaches different colors to each biome and a smaller map feature for each habitat. I really would have found such a map very useful for envisioning these biogeographical changes.

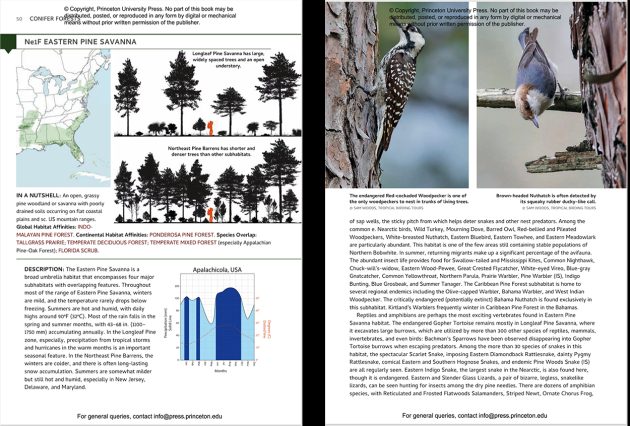

Each Habitat chapter starts with a header showing the unique abbreviation for the habitat and its name in distinct large type, bordered on the left (or right) with the color code for the larger biome section. The opening section aims to give succinct, memorable information for readers who are browsing or who need their habitat information immediately: a map shows the area(s) where you can find this habitat; a Habitat Silhouette of the distinctive trees and shrubs of the habitat drawn on its typical height and structure with a human silhouette posed in dark orange, giving us a sense of physical proportion; an “in a nutshell” summary of what makes the habitat distinctive; Global Habitat Affinities (habitats from other countries that are structurally similar); Continental Habitat Affinities (other North American habitats that are similar); Species Overlap (habitats with similar bird and mammal lists). The longer text offers a detailed Description of the vegetation, climate, and ‘life’ of the habitat, the interaction of elements–fire, winds, soil minerals, water levels, seasons–that make it work. Each description is different in what is emphasized because each habitat is distinctive. A climate graph shows typical rainfall and temperatures, and many descriptions also contain a Köppen climate classification code (you must read the Introduction to fully understand these tools).

© 2025 Phil Chaon, Iain Campbell, and Ben Knoot, Ne1F Eastern Pine Savanna, pages 50 & 54

© 2025 Phil Chaon, Iain Campbell, and Ben Knoot, Ne1F Eastern Pine Savanna, pages 50 & 54

The Wildlife section is the one we birders will probably read most thoroughly. It focuses on birds and larger mammals likely to be found in the habitat, with a special emphasis on species that will only be found there and no place else. Indicator species (species that reflect the state on an environment) and endemics are identified and often pictured. The breadth of these sections is often broad, including reptiles and amphibians. For Eastern Pine Savanna, for example (sample pages pictured above), we learn that in addition to the large mammals common to most eastern Nearctic habitats, we may also find the less common Nine-banded Armadillo, who likes the sandy soil. And that three indicator bird species–Red-cockaded Woodpecker, Brown-headed Nuthatch, and Bachman’s Sparrow–are distinct to this habitat, particularly the woodpecker, which nests in its mature Longleaf and Loblolly Pine trees. And that there is a long list of fascinating reptiles and amphibians that may be found there, including Gopher Tortoise, Pine Woods Snake, Pine Barrens Tree Frog, and a new species of aquatic salamander. I’ve driven through and birded pine savanna habitats in New Jersey, Georgia, and Florida, and I’m thinking that I must go back because I had no idea these areas are so rich in creature life.

The Conservation sections are highly detailed and often sad, addressing survival concerns of tree, bird, and animal species and the survival status of the habitat as a whole. Using information from NatureServe and other sources, they address well-known issues (Hawaii!) and habitats whose conservation status have been neglected (Pacific Chaparral in California, where there are now fires every year). There are triumphs too. The section of Eastern Pine Savanna points out that the tiniest, most diminished subhabitat, High-quality Longleaf Pine Savanna, receives the most conservation attention because of efforts to save the endangered Red-cockaded Woodpecker.

Distribution expands on the map, giving details about where subhabitats are found, where there are habitat overlaps, and what types of habitats occur next door. Where to See gives examples of places where the habitat is located, mostly public preserves, refuges, national parks and conservancy areas, but also, especially for the water habitats, bays and coasts. The lists are frustratingly short, presented us, the readers, with the challenge of identifying the public and private areas where we bird. Looking at this photo I took earlier this year of Antelope Valley, California, for example, I puzzle over its specific desert habitat. Antelope Valley is part of Los Angeles County and the habitat there can quickly change from sod field to suburb to this alien-like landscape. I finally decide that it’s Mojave Desert habitat (Ne2C, pp. 90-94), a transitional desert where Joshua trees and Creosote grow and where a birder may see Black-throated Sparrows and LeConte’s Thrashers, the latter one of the few “Mojave specialists,” which I have. Realizing that this location is west of Mojave National Preserve helps cement the identification, though the next time I go birding there, I’m going to look harder at the shrubby plants (using my iNaturalist app, Seek, for identification) and the squirrels (maybe I’ll find a range-restricted Mojave Ground Squirrel), and maybe even snakes and lizards. Knowing the habitat gives us a wider perspective for knowing more living things.

There is a wealth of informational material supplementing the habitat chapters. The Introduction, as I’ve noted, is recommended reading if you are going to get the most value out of this book. It presents the thinking that went behind the series’ classification system, briefly explains the habitat categories, explains the climate material, codes, and diagrams (a challenge for me, I admit), and lists abbreviations. There is a glossary of Useful Habitat Jargon which I think this could have been much longer than its 16 listings (Nearctic, Anthropogenic, boreal, deciduous, and pelagic are just some of the words I would have liked to have seen there). A four-page bibliography lists 99 scientific books, journal articles, reports, and ecosystem entries from NatureServer Explorer, the database created by NatureServe. (The database is free to the public and well worth exploring, it provides information on rare and endangered species and ecosystems in the Americas on the national and state levels.)

The book is copiously illustrated with photographs of birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, and, of course, habitats. The images are large, mostly bright and colorful, sometimes somber and haunting, communicating the feel of the habitat and the diverse beauty of nature. I always love bird photos, but I also was captivated by the habitat landscapes–the Chihuahuan Desert Grassland under a dark storm-filled sky, a river cutting into the stunning reddish sandstone cliffs of the Colorado Plateau, the ethereal beauty of the high elevation forests of Hawaii. It’s to the credit of the authors that they did not allow these landscapes to overwhelm the text. There is a reasonable, readable balance of image and word, and the few full-page, stunning photographs of places and birds fit in as visual exclamation points. Most of the photographs are by Ben Knoot, with other photographers, including Phil Chaon, contributing; credits are given next to the photograph caption.

The Table of Contents nicely presents most of the book’s contents–Introduction chapters, back-of-the-book Index, and, between the two, the 81 habitats and their color codes, and the page numbers of Figures and Sidebars. The Sidebars are 16 informational boxes on habitat-related material. Topics range from the effect of “invasive” Barred Owl expansion on the numbers of declining Northern Spotted Owls in the Boreal Conifer Forest habitat to a description of the Limestone Alvar microhabit found around the Great Lakes, to an intriguing mini-essay on “Pre-Columbian Habitat Modification,” the ways in which indigenous peoples effectively managed their habitats. They are like digressive conversations, sometimes adding context to the main habitat conservation (“Migrant Traps and Fallout”), sometimes pointing us in knowledge directions we might want to pursue on our own. The Index is fairly thorough, giving page numbers for habitats (chapters and other places where that specific habitat is discussed) as well as trees, plants, birds, mammals, and other creatures cited in the text. Page numbers for illustrations are in bold text, and I think it would have been useful to have page numbers for habitat chapters noted as well (it’s always good to have multiple ways to find significant points of information).

The creative forces behind Habitats of North America bring to it shared and unique backgrounds. All three are bird guides with worldwide experience, two (Chaon and Campbell) are co-authors of Habits of the World. Phil Chaon comes from Cleveland, Ohio and worked at various jobs in the field–banding birds in Peru, monitoring Fairy-wrens in Papua New Guinea, surveying bird communities on coffee farms in Kenya–before guiding, first for Tropical Birding, now for Hillstar Nature. Iain Campbell is from northern New South Wales, Australia and originally trained and worked as a research regolith geochemist. He eventually switched to professional birding, co-founding Tandayapa Bird Lodge in Ecuador and Tropical Birding Tours, co-writing wildlife field guides such as Birds of Western Ecuador: A Photographic Guide (with Nick Athanas and Paul J. Greenfield, 2016), Birds and Animals of Australia’s Top End (with Nick Leseberg, 2015), Wildlife of Australia (with Sam Woods, 2013), and the Habitats series. Ben Knoot is from California and has worked for over 14 years at guiding, photography, and photography tours. He now has his own company, Experience Nature Tours, which features photographic tours and consulting.

When we bird, we are not only thinking about plumage and migration, we’re thinking about trees and shrubs and rocks and elevation and humidity and temperature. Maybe not consciously all the time, but we are. We know we’re not going to find a Montezuma Quail in a Jack Pine Forest or a Kirtland’s Warbler in an arid scrubland. Knowing about the ecosystem in which a bird lives and breeds helps us locate a bird, observe it, photograph it, record it, learn the bird. Conversely, knowing the bird helps us understand and evaluate ecosystems, which ones are thriving, which ones need attention from conservationists and policy makers. Habitats of North America: A Field Guide for Birders, Naturalists, and Ecologists continues and expands on the template set by Habitats of the World. Interested birders who are not familiar with the Habitats series can get a flavor of its synergistic perspective by reading the website developed by the series authors: Tropical Birding’s Habitats of the World, an interesting combination of company marketing and informational deep dive (hopefully, the promised lists of birds for each habitat will be added soon). Habitats of North America is a different kind of field guide. The authors have strived to present complex information in readable, understandable text, complemented by diverse, attractive visual tools and images, in a book package made for constant use and browsing. I think birders of all levels will find a lot to learn and use in this guide, and I’m very happy we have one for all of North America.

Habitats of North America: A Field Guide for Birders, Naturalists, and Ecologists by Phil Chaon & Iain Campbell; photography by Ben Knoot

Princeton Univ. Press, 2005;

ISBN-10 : 0691245061, ISBN-13 : 978-0691245065

376 pages; 550+ color figures; 5.91 x 1.02 x 8.27 inches; 1.7 pounds

$35.00 (discount from the usual sources), also available in eBook formats

Leave a Comment